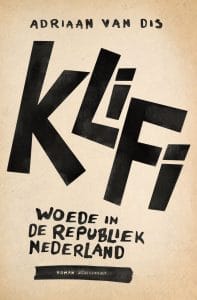

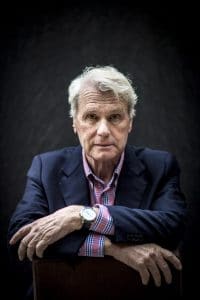

It is a fresh and lively book, the new novel by Adriaan van Dis (74). In his characteristic humorous tone, Van Dis cuts into KliFi the big themes of our time: climate change, the refugee crisis, political populism, (im)freedom. When a crushingly hot summer in the republic of the Netherlands turns into a hurricane and wipes out a village of refugees, president and media are silent about the disastrous consequences. Retired protagonist Jákob, the son of Hungarian refugees, rebels against it.

Writing this spirited book was a welcome distraction for Van Dis in this coronation time. 'As a writer, you live off lectures and gigs, and that has completely fallen away,' he said. The second lockdown I find many times worse than the first one. If your feet can't go somewhere, your head starts craving it terribly. I feel like going to the pub anyway. I used to go out for dinner and drink too much, or after three days of appointments I would think "damn, now I have to work", and then I would work very hard that week to make up for my sinfulness. But there is no more sinfulness, I have become a good guy who sits inside every night. When I finish reading, I watch all possible and impossible war movies before bed. Then the limited life outside is not so bad again.'

Happy anger

Did this story stem from worry or mostly from anger?

'Out of gleeful anger. I belong to the rare breed of people who talk to the radio all day, about everything I hear and disagree with. Let me preface: I have no message whatsoever. As a writer, I have only one job: to write good sentences. At the same time, I do believe that if we want to make some sense of the enormous problems that await us, imagination is a wonderful tool for that. I cannot read Anne Vegter's poem 'The Other Side' without bursting into tears. It's about a disaster that falls over the Netherlands, forcing us all to flee, though no one knows where - to 'the other side'. Suddenly we are refugees, we are called fortune seekers.

'Out of gleeful anger. I belong to the rare breed of people who talk to the radio all day, about everything I hear and disagree with. Let me preface: I have no message whatsoever. As a writer, I have only one job: to write good sentences. At the same time, I do believe that if we want to make some sense of the enormous problems that await us, imagination is a wonderful tool for that. I cannot read Anne Vegter's poem 'The Other Side' without bursting into tears. It's about a disaster that falls over the Netherlands, forcing us all to flee, though no one knows where - to 'the other side'. Suddenly we are refugees, we are called fortune seekers.

The title KliFi - climate fiction - is a jab at those who still deny that anything is wrong with the climate. We all hope that after this pandemic a 'normal' occurs. But there will no longer be a normal, dear readers, because then things will get really serious. Decisions await us that will irrevocably restrict our lifestyle. Not only because of global warming, but also because we will have to find solutions for the millions of climate refugees already roaming the world. Wars are already being fought over rivers. It is self-serving to worry about that.'

Because our own lives are at risk?

'Yes, because what do such big problems invite? To the rise of men - and probably the occasional woman - with firm opinions: the little dictators. We humans adapt very easily, get used to everything. And a dictatorship is like a skin: you grow into it. I wanted to write something about that in a roguish way.

We will have to look with more humanity at all those who are adrift. Whatever the causes, the fact is that the earth is warming and certain parts of the world are no longer habitable. I lived in Paris for seven years, and there I met people from Chad who had fled the drought. A country like Mali is being erased by the desert. Somehow, here in the Netherlands, we are preoccupied all day with ourselves, with our curfew, with all the parties that are taken away from us. That's all very bad and I feel terribly sorry for us, but try to think for one minute about the refugees in Camp Moria. I understand looking away all too well, but we have to do something. But now I am almost starting to sound like a vicar, whereas in my book I try to make this clear in a light-hearted and cheerful way.

Alien

You have seen the Netherlands and the world change dramatically in 74 years.

'When I come to schools, I am like E.T., a creature from another planet. I tell them that in my youth in Bergen aan Zee we had only one telephone in the whole village: one of those black antlers with a horn on it. And I tell about the flood disaster; because in Bergen aan Zee, too, the dunes had broken through. My parents were sitting by the radio at ten o'clock in the morning, one of those very big machines with a flickering eye. Then all these schoolchildren look at me: what a crazy man, and what crazy words he uses. They think I'm completely nuts. But it inspires me enormously to talk to them, to build a bridge. I used to come to schools to tell them something, now I mainly listen.

So what do you hear?

'For example, that the boys aged 16 and 17 are trapped. The girls have become extremely empowered and are overtaking them on all fronts. So those boys with all their testosterone are looking for holdouts with the tough guy type and are very conservative, out of fear. And they have to perform so hard, huh, everyone has to succeed in life right away. I just stayed down a few times, and studied for 11 years. It is an absolute requirement to walk in seven ditches at once in order to eventually be able to walk after the ditch. Succeeding right from the start, having to know at sixteen what you are going to be - what an incredible task are we setting these young people? We are setting up a world where everything is ordered and fixed, where everyone's identity is determined at an early age'.

Edge figures

Why do we do that?

'Out of fear, insecurity and mistrust. Every day I take the same walk and sit on a bench at a shelter where men live with hip flasks of alcohol and walkers, who are a bit stranded in life, and strike up conversations with them. That's how I hear stories about how hard it is to hold your own in life. I plead for all the crazies, idiots, fringe characters and misfits, because they enrich our lives. All madness is also within ourselves.'

In your book, you write that we should nurture cross-thinkers. But that is usually not what happens.

'No, and I also surprise myself at how much I adapt and censor myself. In daily life, we are feigning all the time because we don't want to bring issues to a head. But through that feigning and adjusting, we end up creating an unfair world. Everything you do wrong is immediately on the internet these days. So even the possibility of making a mistake or being wrong is already fixed, literally: you end up getting it all back on your plate. That breeds dishonest people. A society of haggling.'

Whisper

What is most wrong in the Netherlands?

'I worry most about populism; the people in the wings eager to kick up a fuss. We are in a state of chaos, with a lot of anger and confusion, and ministers who are not up to the task. Before you know it, we ourselves are begging for intervention by a strong man or woman. Democracy is very fragile, and a time like this invites very undemocratic forces.'

What can an almost activist book like Klifi against that?

'I am a desperate optimist. If you touch just one person, it can change the world. A whisper can have the effect of a megaphone in a lifetime, I firmly believe in that.'

Is KliFi became such a snappy book because it was an outlet?

'Well, I could find some mean-spiritedness in it, yes. I loved putting down a president and playing with his ideas. I hope it also provides a momentary escape for the reader and, besides the pleasure of a few good sentences, also leaves her with a slight sense of discomfort.'

Open mind

You once said you were afraid of becoming an old, grumbling, embittered fool. Are you still?

'Yes, and that is why I try to unbitter myself every day. By looking evil in the face and staying aware that it is also in myself. I spent a long time in psychoanalysis and then you do learn to deal with yourself. That may sound self-righteous and coquettish, but it is mostly a form of self-protection. On Paris, I often talked to drunk clochards. I was afraid of them, and that is precisely why I tried to overcome that fear. Confront yourself with opposition, it keeps your mind nimble. Or in the words of Frank Zappa: 'The mind is like a parachute; if it is not open, it does not work'. Later, when I am at my 92e living with my walker in a care home, I want to be able to feel at home with a Somali director. I want to be ready for my own time.'

An open mind also keeps youthful.

'That's true. About four years ago, I suffered from depression. My mother had died and my last sister also died. No witness left alive. That made me very gloomy. I wanted to die. The psychiatrist recommended mindfulness to me. I visited a woman who gave it to delinquents in prisons. She made me look at walnuts for half an hour - go figure. But it helped me a lot, including all the breathing exercises. Now when I feel nervous or gloomy, I try to breathe in and out for ten minutes and imagine I am a mountain. Even if you have 10 years of Rutte and 50 years of Wilders, that mountain remains a mountain, untouched. A second lesson was that good seeds lead to good plants. I resolved to be nice five times a day, by giving way to someone at the cash register, greeting the tram conductor or bus driver. Mind you, hardly anyone does that. Such a boa who stands directing traffic is scolded all day long, especially here in Amsterdam. I have noticed that if I am nice to someone five times a day, it is both pleasant for the other person, but it also goes better with me five times.'

KliFi. Anger in the republic of the Netherlands, AtlasContact, € 21.99