For eight years, the Mauritshuis researched and restored his painting 'Saul and David'. As a result, it can now be definitively attributed to Rembrandt. But the small exhibition 'Rembrandt? The Case of Saul and David' mainly shows how the museum collaborated with all kinds of different scientists and laboratories to unravel the numerous mysteries surrounding the canvas. As a visitor, you become a bit of an expert by watching yourself. You may even use your fingers to probe what the paint layer feels like!

The painting of the biblical King Saul, dejectedly listening to the harp-playing young David, was shrouded in mystery. Ever since its purchase in 1898 by Abraham Bredius, there had been questions: is it or is it not by Rembrandt? What has been restored and cut up about the canvas over the centuries? In how many stages was it painted? And why nowhere else in art history do we see Saul drying his tears on a curtain, as if it were a handkerchief?

As a Mauritshuis, you cannot afford to claim a real Rembrandt if you are not very sure. 'We did our best not to attribute it to Rembrandt,' says director Emilie Gordenker, then, 'but we couldn't avoid it.'

The museum has been working on the painting since 2007. Under many thick, dirty layers of varnish, it turned out to be composed of several pieces, cut loose and put back together with serrated seams. A strange puzzle, with the part at the top right also appearing to be cut from a completely different painting - a copy after Anthony van Dyck.

Fortunately, modern technology could bring more light to the matter. The Mauritshuis had been collaborating with natural science experts before. The business community did not shirk either. Shell, for instance, helped with paint analyses during the museum's renovation.

Reborn

The exhibition 'Rembrandt? The Case of Saul and David' is really about two things. Obviously about the restored canvas and a number of works by contemporaries, providing art-historical context. 'Saul and David' looks like it has been reborn, full of details not seen before. The painting has not been put on a new canvas, but left intact as it was. A primer (removable if necessary) has been applied over the non-authentic part. It is visible which parts are original, but this does not disturb the perception of the painting.

CSI

But certainly just as important in the exhibition are the techniques used. Through multimedia presentations, the viewer takes a look inside the studios and laboratories. In a CSI-like atmosphere, you feel yourself becoming a little expert as you gain more and more insight into the research methods - and their often far-reaching conclusions.

A few examples. At the edges where a painter's canvas has been stretched with strings or nails, small distortions ('spanguirlandes' in jargon) occur. By taking X-rays and measuring thread density, it is possible to find out exactly where the edges of the original canvas ran. In the case of 'Saul and David', this was not always in the place of the current edge. Pieces were cut away and, among other things, a strip was stuck on the right that did not belong there. By milling out the frame deeper there and sliding the canvas a bit 'into the frame', we now see that right-hand edge again as it was intended.

Curtain as handkerchief

Another example. Paint cross-sections of the curtain already pointed to the master's hand, but advisory Rembrandt expert Volker Manuth thought it unlikely that Rembrandt had Saul wiping his tears on the curtain as if it were a handkerchief. Moreover, the curtain was heavily repainted and could have been added later. Outcome offered the XRF scan, a special kind of X-ray from TU Delft and University of Antwerp.

Rembrandt and contemporaries used smalt as a blue dye, made from finely ground cobalt glass. Later, it was replaced by cheaper dyes. Joris Dik, professor at TU Delft, can use the XRF scan to isolate any chemical element. That was done with cobalt in this case. On that scan, it is excellent to see that the curtain was painted with smalt and was therefore there from the beginning. Dik: 'For the more subjective art-historical interpretation, we have provided objective evidence.'

All the research results together, combined with the better visibility of details after the restoration, led to the conclusion: yes, it is a Rembrandt. The dating has also been adjusted slightly: first phase in the early 1950s, second phase in the mid-17th century.

Feel!

For those who don't just want to look, Océ Technologies in collaboration with TU Delft created a very special piece: a 3D print of the original parts of the canvas, at the size the painting originally had. The paint layer has been precisely imitated with all its craquelé and relief. And you can feel it.

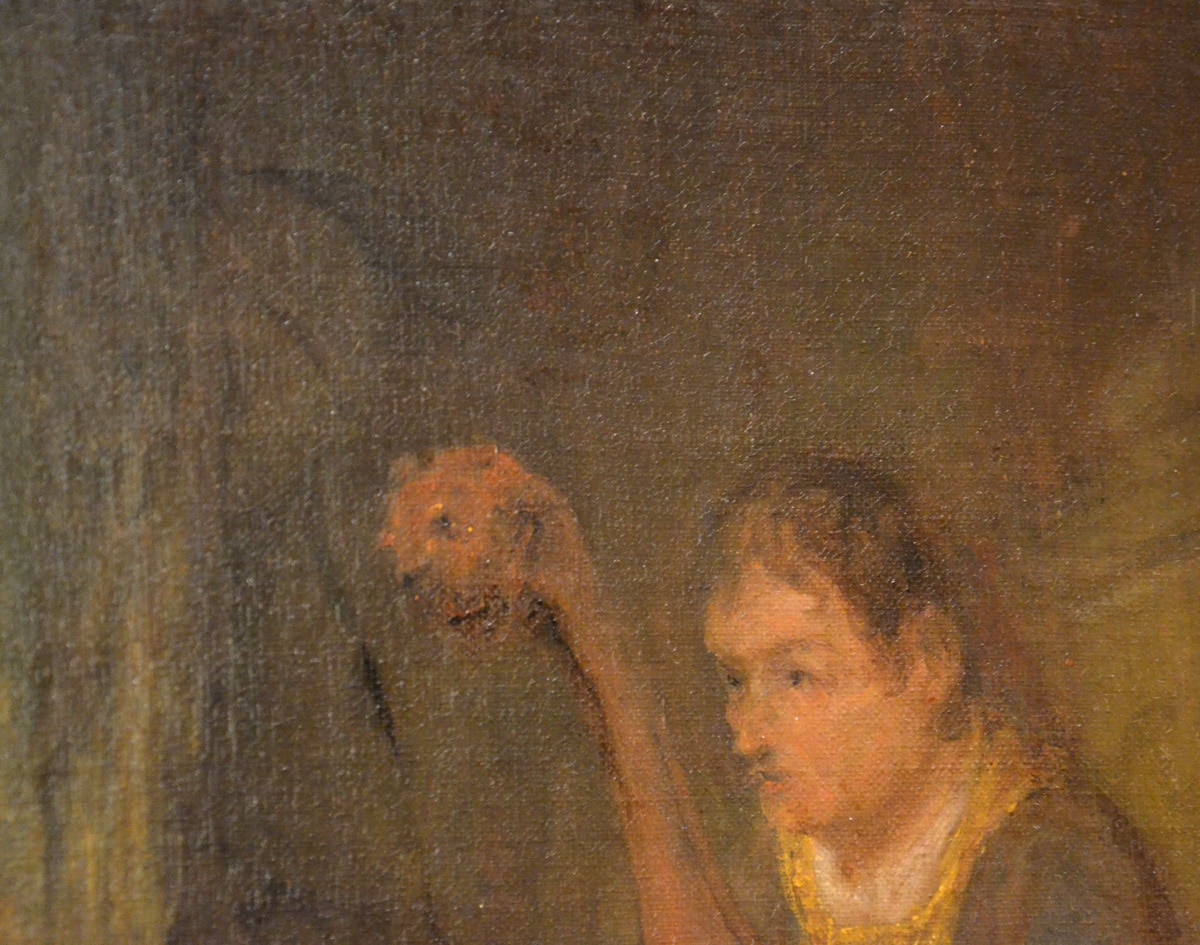

By the way, Rembrandt's brushstrokes do not feel as thick as you would expect in his late period. According to Susan Smelt, who collaborated on the project as conservator, this has to do with the re-covering process in the 19th century: 'That involves a lot of heat and pressure, which made the paint flatter.' Nevertheless, we recognise the rougher painting style of the older Rembrandt. Smelt: 'I see Rembrandt before me as a kind of Karel Appel, who really tackled the canvas with his palette knife or the back of his brush.' She shows how Rembrandt's pupil Arent de Gelder also applied these techniques to a painting with the same representation, but in De Gelder's case it feels more like a trick than in the master's. Smelt: 'Yet in his later years, Rembrandt's pupils sold many more portraits than he did himself.'

Peeking around the corner

That little painting by De Gelder, a loan from the Kunsthalle in Bremen, incidentally also offers a clue as to what may have been at the vanished corner of the painting. Around the curtain at De Gelder, in fact, a head with a hood peeks out. We do not know for sure, but it is conceivable that in Rembrandt's painting, too, a third person (David's wife?) may have been watching the scene.

What we do know for sure is that we can once again enjoy a beautiful Rembrandt, in very much better condition, rich in detail. As if we were looking around the curtain at Saul and David ourselves for a moment.

Rembrandt? The case of Saul and David, Mauritshuis The Hague, 11 June to 13 September 2015

Cover photo: Feeling the 3d scan (author's photo)