Als jongen kwam ik al graag op de Egyptische afdeling van het Rijksmuseum van Oudheden in Leiden. Half in de schemering staarden mij daar de mysterieuze mummiekisten aan. We zijn nu enkele decennia en opstellingen verder. Sinds deze week is de nieuwste Egypte-opstelling open. Ook in stralend licht blijkt de collectie haar fascinerende kracht te behouden. Tegelijkertijd vertelt het museum in Koninginnen van de Nijl het verhaal van de vrouw in het oude Egypte, met veel bijzondere bruiklenen.

Het Rijksmuseum van Oudheden in Leiden vernieuwt zijn vaste opstellingen in fasen. Vorig jaar was de klassieke oudheid aan de beurt, volgend jaar de archeologie van Nederland en nu de nieuwe Egypte-presentatie. Het museum bezit het welhaast schrikbarende aantal van 25.000 voorwerpen uit de Egyptische oudheid; er staan nu een nauwelijks minder schrikbarend aantal van 1.400 stukken opgesteld.

Terug naar Sakkara en Abydos

Het RMO verwierf al begin negentiende eeuw een grote collectie Egyptica, vooral uit Sakkara en Abydos. Egypte stond in de belangstelling na de veldtochten van Napoleon. Het gold als geaccepteerd om originele kunst mee te nemen. In de jaren zeventig van de twintigste eeuw keerden het museum en de Universiteit Leiden terug om na te gaan of er nog iets te vinden was dat de vondsten meer context kon geven. Tot verrassing van de onderzoekers waren delen van de oorspronkelijke vindplaatsen nog intact en konden bijvoorbeeld reliëfs uit de Leidse collectie moeiteloos worden ingepast in grotere wandtaferelen.

Voor de nieuwe opstelling heeft het RMO gekozen voor een introductiezaal met de chronologie van de Egyptische oudheid en vier themazalen. In die laatste krijgen we een venster op de godenwereld, de visie op het hiernamaals, monumentale beeldhouwkunst en de wederzijdse inspiratie van Egypte en andere culturen.

Nieuwe aankopen

Om de verschillende verhalen zo goed mogelijk te kunnen vertellen, stelde het museum veel voormalige depotstukken alsnog op en deed het zelfs enkele nieuwe aankopen. Door de sublieme verlichting door Chris Pype Licht uit Schaarbeek (België) stralen de stukken als nieuw en geven ze veel voorheen moeilijk zichtbare details prijs. Op twee plaatsen kunnen we een tempelfragment betreden; ook hier maakt het licht in combinatie met gebruik van museumglas dat de duizenden jaren tijdverschil praktisch wegvallen.

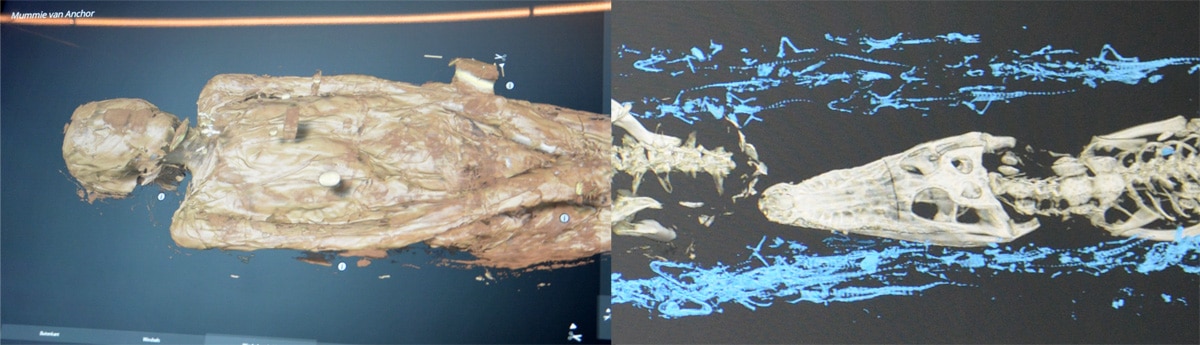

Babykrokodillen

Een fascinerend nieuw gegeven kwam boven water toen het RMO twee mummies opnieuw liet scannen met medische apparatuur. De grote krokodillenmummie bleek al bij een eerder onderzoek niet één, maar twee krokodillen te bevatten. Nu blijkt dat de mummie tussen de windsels nog een enorme hoeveelheid gemummificeerde babykrokodilletjes herbergt. Op touchscreens is ieder detail daarvan te zien. In lagen kun je zelf de windsels uitpakken, het skelet, de schubben en alle doorsneden bekijken. Hetzelfde is gedaan met een mensenmummie, die ook alle bijgevoegde amuletten en sieraden laat zien.

Als levenslange RMO-bezoeker mis ik in de opstelling de mummie van een kind, dat al lang geleden van zijn windsels is ontdaan. Het museum heeft ervoor gekozen het kwetsbare naakte jongetje niet langer aan nieuwsgierige blikken prijs te geven. Enerzijds begrijpelijk, anderzijds toch ook jammer. Als enige uitgepakte mummie in de collectie liet het kindje zien hoe gelooide huid eruit ziet, hoe een gat in de buik werd gemaakt voor het verwijderen van de ingewanden. Het maakte vooral ook voelbaar hoe dichtbij een mensje van meer dan 3000 jaar oud kan zijn en dat verdriet en ontzag voor de dood van alle tijden zijn.

Koninginnen van de Nijl

Eigenlijk zou je na zoveel informatie de tentoonstelling Koninginnen van de Nijl een andere keer moeten bekijken. Ruim opgezet zien we hier de glorietijd van de koninginnen van het Nieuwe Rijk in al haar facetten. De keuze voor deze periode sluit beroemdheden als de Hellenistische Cleopatra uit, maar met koninginnen als Nefertiti en Hatsjepsoet hoeven we daar niet rouwig om te zijn.

De farao had als enige Egyptenaar meer vrouwen, maar zijn officiële vrouw, de Grote Koningin, onderhield net als haar man rechtstreeks contact met de goden. Tevens bestuurde zij de harem en regeerde in sommige gevallen (bijvoorbeeld Hatsjepsoet) zelfs als farao door na het overlijden van haar man. Na haar dood werd de Grote Koningin begraven in de Vallei der Koninginnen, dus gescheiden van haar echtgenoot. Aan de konings- en koninginnengraven werkt gewerkt door ambachtslieden in een speciaal dorp, Deir el-Medina. Ook hiervan zien we ruwe materialen. Intrigerend is ook de vijf meter lange ‘samenzweringspapyrus’, die vertelt hoe farao Ramses III door een complot vanuit de harem werd vermoord.

Koningin als heilige

De tentoonstelling telt veel bruiklenen, vooral uit het Museo Egizio in Turijn, maar ook reconstructies, bijvoorbeeld van één van de grafkamers van koningin Nefertari en van het uiterlijk en de hoofdtooi van een koningin.

Op het affiche prijkt een klein houten beeldje van de vroege koningin Ahmose Nefertari. Zij verwierf al bij leven een goddelijke status en diende voor veel eenvoudige Egyptenaren als tussenpersoon tussen de mens en het hogere. En al moeten we oppassen met te makkelijke vergelijkingen, dat doet toch een beetje aan als de rol van heiligen in het Katholicisme. Af en toe voelt het oude Egypte best dichtbij.

- Koninginnen van de Nijl, tot en met 17 april 2017

- Vaste Egypte-presentatie op website RMO