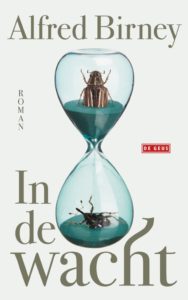

Shortly after Alfred Birney signed for The interpreter of Java received the Libris Literature Prize, he ended up in hospital with a heart attack. In his new novel On hold Birney's alter ego Alan Noland lies in hospital waiting for open-heart surgery.

He was just beginning to feel somewhat fit again after his five-way bypass surgery and two years of recovering, when life came to a standstill again - this time due to corona. Alfred Birney's (68) laughter echoes into the room via Skype; unlike his protagonist, who grumbles and swears quite a bit, the writer is good-humoured and rather cheerful under the situation. Birney lives alone, so being on his own was something he was already used to. 'The most annoying thing is that my health requires me to cycle for an hour three times a week, but that's slipping away now. I did have a mouthpiece made, but I don't dare to do it yet.'

How is your health now?

'I was finally on the rise, my recovery took a long time. A few months after I won the Libris Literature Prize, things went wrong. First I got a hernia and when I recovered from that, I ended up in hospital with a heart attack. I had already had a heart attack once in 2006. The doctors showed me pictures: it was chaos inside. The coronary arteries should run around your heart like amazon rivers, but in my case those rivers all had branches. When I asked what my chances were without open-heart surgery, they replied, "Well, you will still make it through Christmas, but not New Year's Eve." I was given five bypasses. A few weeks after the operation, it turned out that one of the bypasses had come loose. Being on the heart-lung machine had changed my breathing rhythm, which in turn affects your brain. As a result, my short-term memory was also failing and I suffered from anger attacks. You always read that you can drive a car again six weeks after such an operation and that you are completely recovered after six months, but with me it took two years. And I still feel pressure on my chest when stressed.'

So how exciting is it to be alone?

'Well, if something happens again, I have to call 112. And if I go into cardiac arrest and can't call again, I'll die.'

You say it very calmly.

Birney laughs hard. 'Yes, because I don't think you notice that much because you pass out pretty quickly. The ambulance should be with you within seven minutes, but as early as five minutes you can get brain damage. So basically they should be there within two or three minutes; that's when you have the best chance. That works if you are at a busy station with an AED nearby, but if you are alone at home, then you are seen. I don't think about that too much.'

Channelling

Was writing On hold, about your time in hospital, a way to channel your emotions?

'I think so. Early last year, I started a new book but got stuck on page 20. I didn't like it, threw it away and emailed my editor that they should just send out a press release that I was quitting writing. He immediately hung up the phone to dissuade me from that. So I tried again - same song. I kept thinking back to that time in hospital, to that operation and the whole aftermath. My dreams were always about death. I decided to have my alter ego Alan Noland, who has been my protagonist many times before, lie in the hospital and go through what I went through. That worked.'

Your novel is not only about your history of illness, but also about larger themes, such as multiculturalism.

'Indeed, I wanted to write off the anxiety and stress I suffered from those admissions and heart surgery, but also tell a bigger story about the remnants of tropical or colonial Holland. It is always said that the multicultural society has failed, but on that 50-bed cardiac ward it was multicultural - Surinamese, Hindustani, Chinese, Javanese, Indos, everything was there. Through that department, I wanted to give the multicultural society a face. In such a place, there is no escape, so how do we treat each other? I wanted to show that that colonial structure of yesteryear is still permeating our present day.'

Racial versus racist

You write about the difference between the racial eye and the racist eye. Where exactly does that difference lie?

'A racist looks down on another because of his appearance or origin. If you look with a racial eye, you can see the differences, but without those feelings of superiority. The two are often confused in debates, but noticing cultural differences is not necessarily racist. If I order in a coffee shop from a Dutch waitress, I can say: 'Hi, may I have a cup of your coffee?' That is not a rude way of talking to a Dutchman. If you visit a Turk or Moroccan then you know you have to take off your shoes.... As an Indo, I have had to deal with racism all my life; I really didn't enter some cafes, to name a few. But I see nothing bad in it when a Dutchman says, 'But you Indos do this or that, don't you?' We have to immerse ourselves in the other, try to understand the other. And we can't do that if we pretend to be colour-blind and deny differences. It is only when we know more about each other's culture that contradictions can be bridged, whereas we are currently stuck in black-and-white polarisation.'

Swearing

It's not the only thing your alter ego fusses about - especially at the beginning of the novel, Alan is lying down and swearing at everything and everyone. You write: 'protesting and swearing, by the way, causes stress'. Didn't writing this book raise your own blood pressure, then?

Cheerfully: 'Ha ha, yes, I became a heart patient for a reason, of course! Apparently, I was walking around with all kinds of frustrations that I still had to get rid of, such as the influence of the pharmaceutical industry. I myself, but also my son who has asperger's, fell prey to that. My cholesterol was 2.2 - quite fine, as the value should be below 5. Yet the doctor suddenly made me take pills to bring it down to below 1. I got sick of those pills! I refused to take them any longer. Meanwhile, more and more general practitioners are saying that such standards mainly benefit the pharmaceutical industry, not the patient. Such things worry me, and as a novelist I use those thoughts and suspicions. It is not non-fiction and I do not have a monopoly on truth, but I am allowed to express suspicions in my novel.'

Pandemic

Noteworthy that your protagonist also fantasises about a pandemic: 'Otherwise, spread a sophisticated bacterium around the world at random, somewhere in central China, that ticks nicely, that bacterium will just hitch a ride on the annual flu waves, until the earth is populated again by about a billion and a half people'.

I got the typesetting proof of my book back and I thought: heavens! There has to be a footnote here, because I wrote this a year ago, well before corona broke out. That whole nasty virus is not something you can mock, so I wanted to avoid people thinking I was making a silly joke about it. I had my protagonist fantasise about unleashing a disease to address the great taboo among taboos: overpopulation. Because by now we can talk about black Peter, slavery, sexism and transgender people, but not, until recently, overpopulation. But what do we see happening now: because of corona, suddenly people are discussing selection; from what age people should just not be treated.'

Parent-child relations

It is also a novel about parenthood. Alan has a troubled relationship with both his mother and son.

'Alan's parents divorced young, and like me, he grew up in a boarding school. The interpreter of Java was already about the violent father, now it is the mother's turn. And I wanted to write about my son. Alan, although unable to lead a normal family life himself, has tried to do better with his own child all the things his father did wrong. But his son visits him less and less often and his mother does not visit him at all. He imperceptibly grows weaker and weaker, so his grumbling also declines. Eventually, you see more and more of his vulnerable side.'

Blown off

Were you actually able to enjoy that Libris Prize a bit?

Another burst of laughter. 'Yes, it was great! When I got it I was already not doing well, but was still sent home by the GP. After I got the award, I was suddenly a star and had three performances a day. Everywhere I went I got applause and long lines of people were waiting for an autograph. Wow! But I didn't realise I was running purely on adrenaline, and yes, that's when you just collapse after six weeks. I was supposed to go to Frankfurt, to Brussels and Ghent, even to Italy, it all fell through. I also had to cancel the visit to Máxima and Willem-Alexander, even though I had had a special royal copy of my novel made. Anyway, I could have died too.

Still unfortunate that now your next novel is appeared, you can't go out again.

'I just console myself with the thought that I am not the only one. For all those young writers, it's much worse. But indeed: for On hold I cannot visit bookstores to sign now. The English translation of The interpreter of Java, which was due to appear in June, has been cancelled for the time being. And Italy is also on hiatus AND mad at the Netherlands, so it remains to be seen whether the translation will appear there. But what a great stroke of luck: I have had money worries all my life, always. For the first time in my life, winning this prize means I don't have that now.

On hold is published by De Geus, €22.50