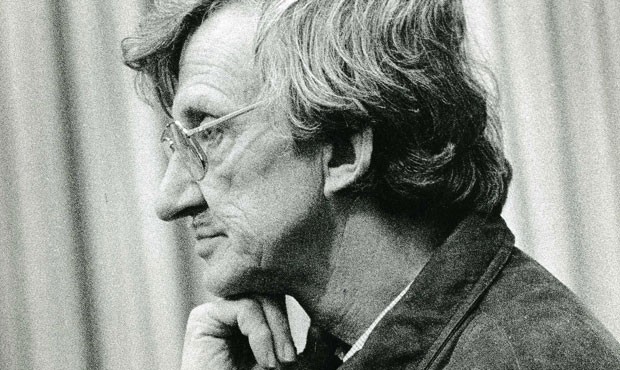

Ton de Leeuw lived in Paris for the last decade of his life and studied with Olivier Messiaen in his younger years. At 21 May Cappella Amsterdam will present four of his French-language choral works in the Muziekgebouw aan 't IJ. The programme also includes works by his student and friend Daan Manneke and the young French composer Laurent Durupt. Eight questions to chief conductor Daniel Reuss and composer Daan Manneke.

Ton de Leeuw is considered one of our greatest composers of the last century. What makes him special?

Reuss:

There is no doubt that Ton de Leeuw is one of the greatest Dutch composers. He has devised a music system all his own, influenced by Eastern music. In it, he created very consistent and meditative music that was harmonic and French-oriented. He also wrote a lot of French-language vocal music.

Manneke:

Ton de Leeuw was an internationally sought-after and esteemed teacher: people flocked to Amsterdam from all over the world to study composition with him. I had taken a music aesthetics course with Olivier Messiaen in 1968, and recognised the same undogmatic and open attitude towards composition in De Leeuw. It was clear to me that he should be my new teacher. In our country, he was considered idiosyncratic and unorthodox, because he broke away from common styles. He developed his own voice, more focused on exposure than development.

He himself compared his method of composition to the workings of a kaleidoscope. The pattern seems dynamic because the colour palette is constantly changing, but no colour is added, nor is one subtracted. It is a self-revolving whole, creating the illusion of movement. Thus he created a circular experience of time, like a kind of 'eternity' in a spiral musical staircase. Ton is very dear to me; as a tribute, I wrote my Tombeau pour Ton de Leeuw 1926-1996, to which my latest CD named.

How do you explain that his music is nevertheless performed relatively infrequently?

Reuss:

It is indeed a mystery why his work is so rarely programmed, because every time Cappella Amsterdam performs it, audiences are very impressed. It is accessible and beautiful-sounding music that everyone immediately recognises.

De Leeuw studied with Messiaen, do we hear that in his choral music?

Reuss:

Messiaen composed in a different system, but in Elégie pour les villes détruites you do hear Messiaen-like chords. Moreover, his teacher's language is generally more dissonant and exuberant, perhaps also because of his Catholic background. Messiaen is not afraid of grandiose effects, De Leeuw writes more cautiously and subdued.

Ton de Leeuw studied Indian and other eastern music. Did that influence his own compositions?

Reuss:

Certainly, you can clearly hear that in his music. Among other things, he works with heterophony, unison melodies that derail, for instance at the end of Car nos vignes sont en fleur. And in the use of gamelan-like effects, the influence from Indonesia is easily recognisable.

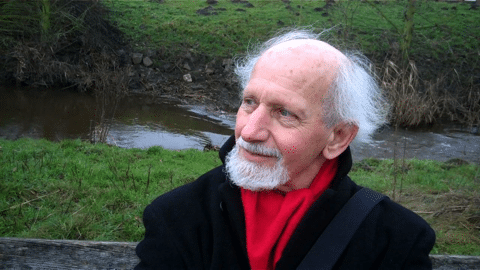

Alongside the music of Ton de Leeuw, Psalms by Daan Manneke will also be heard. Are there any musical interfaces?

Reuss:

Manneke has developed his own style, but in his early works you can hear a connection with De Leeuw; later, he aligned himself more with someone like Arvo Pärt. Another connection is that Manneke also wrote many French-language pieces.

Manneke:

I do think my music has common ground with Ton de Leeuw's. This is in the use of modality rather than a rigid atonal system, for instance. We also both have a feel for vocal, linear thinking and a 'Romanesque' sonority with long, cantando lines. We also share a fondness for the French language, which generates a certain loftiness and monumentality.

Forty years lie between the creation of Psalm 121 and Psalm 122 by Daan Manneke. Are they similar or very different?

Manneke:

I grew up in Zeeuws-Vlaanderen and wrote Psalm 121 when I was twenty-one for a Catholic church choir from Sint Jansteen. In this youthful work, you can hear influences from Francis Poulenc, early Messiaen and Hugo Distler, as well as Sweelinck and the Geneva Psalter. Although I had few composing tools at the time, the piece was included in an anthology by a major publisher. It is still sung somewhere around the world every week, a feat of beginner's luck.

Although half a lifetime lies between the two settings, during which I also wrote avant-garde music, there are similarities. For instance, in the use of modality, the sonority of French and the beautiful symbol of the number forty. But Psalm 122 is much more nuanced, symphonic and lusty. The text gives reason for that too. To make a comparison with instrumental music: you could think of 121 as a 'string quartet' and 122 as a 'symphony orchestra'. In other words, 121 is Protestant and 122 is Catholic.

There will also be a piece by the young French composer Laurent Durupt, who I know mainly from electronic sound experiments. How does he fit into the programme?

Reuss:

Durupt forms a counterpoint element. He wrote a sound piece, more an etude in overtones than a composition with musical material. There is a link with De Leeuw, because both work with overtones, but Durupt actually uses overtone singing, which we do not hear with De Leeuw.

Which of the three composers writes most naturally for the human voice?

Reuss:

De Leeuw and Manneke's music is written very naturally for the human voice. De Leeuw uses in Car nos vignes sont en fleur incidentally, quarter tones, which we know mainly from music from Asian and Arabic countries. The overtone singing that Durupt presents us with is also not common among us, but is in other cultures, such as Mongolia. Durupt is a bit more experimental than the other two, although in this he harks back to the 1970s. Elégie pour les villes détruites by Ton de leeuw is a ripe piece by a true master.