With Michelangelo Antonioni - Il maestro del cinema moderno, EYE has once again managed to put together a flawless and solid film exhibition. George Vermij visited the exhibition on the Italian master filmmaker and looks back on his influential oeuvre.

In Dino Risi's road movie Il Sorpasso (1962), the passionate and extroverted Vittorio Gassman takes a young and reserved Jean-Louis Trintignant in tow through Italy. In his fast convertible, the folksy salesman tries to impress the shy student a little more by talking about cinema. However, he should have nothing to do with Michelangelo Antonioni. The alienation of L'Eclisse (1962), according to him, is only good for a lovely siesta in the cinema auditorium. Risi's nod to his colleague was, of course, a witty inside joke. Antonioni, you couldn't ignore that as an Italian filmmaker in the 1960s. After all, he had radically changed the language of cinema, whether you found it boring and soporific or not.

Spoiled weltschmerz

Short of Gassman in his glitzy bolide, Antonioni's main themes were alienation, communication problems and the lack of meaning in modern times. This condition humaine he examined mainly through the eyes of the wealthier classes.

Antonioni did not have a monopoly on that world of spoilt weltschmerz. You can also see the theme in Federico Fellini's La Dolce Vita (1960) and in certain Ingmar Bergman films of the time. Antonioni, however, distinguished himself from those filmmakers by refining a bare-bones kind of cinema where all unnecessary ballast was jettisoned. No unnecessary prettification, helpful plot or explaining dialogues. Ultimately, paradoxically, the narrative emptiness in his films was also the content.

That modern approach is a mixed blessing been for filmmakers after him. Antonioni set the tone for international arthouse film with his films, unwittingly creating a template for the generations that would follow him. Overall, it is a movement that adheres to certain stylistic and thematic conventions as much as its commercial counterpart, the Hollywood film. See there the long slow shots, philosophical socio-critical implications and the importance of open endings. Elements sharply dissected in David Bordwell's influential essay The Art Cinema as a Mode of Film Practice. They are still the hobbyhorses of many a self-respecting film director.

Cinephile plume

Antonioni's influential status is of course further emphasised by the museum status his oeuvre is accorded at EYE. In its ambitious scale, it is the definitive introduction to his work. In this, the museum can rightly call itself the best student in the class again. Like the nice compliment EYE received from a satisfied William Kentridge for organising his successful exhibition, this time came praise from compiler Dominique Païni about the pleasant collaboration with Jaap Guldemond, EYE's head of exhibitions.

Païni, as former director of the Paris Cinémathèque, is not the least of these. Together with assistant Maria Luisa Pacelli, the Frenchman reiterated in a press conference that the arrangement in EYE was the best result of this touring expo. For instance, the retrospective had previously been shown at BOZAR in Brussels. Pacelli, as director of the museum of modern art in Ferrara, provided material drawn from Antonioni's personal archive. A variety of items Antonioni had bequeathed to his hometown, including his paintings, but also beautiful letters he received from masters such as Andrei Tarkovsky and Akira Kurosawa.

Peerless appearances

The expo combines this diversity of objects, scattered on display tables, with projections of iconic clips from his films. In a chronological line, visitors are bravely taken through his oeuvre. Asides are about recurring fascinations in his oeuvre or actresses who stood out in his films. The peerless Monica Vitti pops up, of course, but also the lesser-known but at least as enchanting Lucía Bosé, who played in Antonioni's early films.

The heart of the exhibition is the space dedicated to Antonioni's trilogy on modern life. It all started with the scandalous success of L'Avventura (1960). A film that was booed at its Cannes screening, but eventually won a jury prize. The story about a missing young woman turns into an alienating portrait about the people looking for her and the impasse they have reached in their lives. This condition Antonioni would explore further in La Notte (1961) and L'Eclisse (1962). Films that turned traditional expectations about film as entertainment on their head. Or as film critic David Thomson wrote of Antonioni's films, 'A hole has formed in "story" so that life's formless air may seep in.'

Watching it back, it is not cinema you fall in love with immediately. Rather, these are films that feel like harsh confrontations and point you to the inevitable disappointments that lurk in human contact. So aptly articulated by Monica Vitti in her role in La Notte: 'Every time I try to communicate with someone, the love disappears.'

Insecure poetry

Nor is there any place for reassuring closure as you might expect from the escapist dream factory of commercial cinema. In its place is the uncertainty and messiness of open endings and matters that remain unresolved. It is the shock of recognition about disordered and uncertain modern life that Antonioni continues to make so timely. A state that he captures lucidly and at times poetically in beautiful shots such as the mysterious final segment of L'Eclisse.

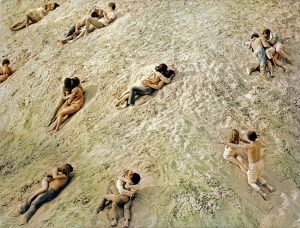

Antonioni's oeuvre has not always been watertight. Blow Up (1966) and Zabriskie point (1970), with their 60s hipness, have stood the test of time the worst. They are mostly time capsules to the groovy sixties. This also made them an easy target for persiflages. See there Mike Myers as Austin Powers who, like David Hemmings in Blow Up sidelines as a fashion photographer in swinging London. And the iconic lovemaking in the desert in Antonioni's American outing Zabriskie Point was mercilessly parodied in the infantile Kevin and Perry Go Large (2000).

Antonioni's last major feat was Professione: reporter (1975) which he co-wrote with film theorist Peter Wollen. In that film, journalist Jack Nicholson assumes the identity of an arms dealer and the story oscillates between a surreal thriller and a hypnotic examination of the fragility of human identity.

The above films will be screened in the accompanying film programme that EYE has put together. It is a perfect complement for anyone who wants to delve completely into the oeuvre of the modern Italian master and share in the modern alienation he knew how to convey so powerfully.

Michelangelo Antonioni - Il maestro del cinema moderno

12 September 2015 to 17 January 2016 EYE film museum Amsterdam