Franz Liszt (1811-1886) werd in eigen tijd vereerd als een ware duivelskunstenaar, die met zijn virtuoze pianospel het hart van menige vrouw op hol deed slaan. Maar vóór alles was hij een vernieuwer, die de ambitie koesterde ‘een speer in de oneindige ruimte van de toekomst te slingeren’. De Concertzender belicht woensdag 2 december twee uur lang leven en werk van Franz Liszt. Om 20.00 uur zoomt Mathieu Heinrichs in op diens relatie met Clara en Robert Schumann, en van 21.00-22.00 besteed ik in Panorama de Leeuw aandacht aan Liszts late scheppingsperiode.

Hoewel Franz Liszt geboren werd in Hongarije sprak hij Duits. Zijn vader was rentmeester aan het hof van de adellijke familie Esterházy, waar Joseph Haydn dertig jaar kapelmeester was geweest. Hun slot lag in het westen van Hongarije, in een gebied waar voornamelijk Duits werd gesproken, zoals ook op de lagere school van Franz. Na de Eerste Wereldoorlog werd het gebied als ‘Burgenland’ aan Oostenrijk toegewezen. Maar Hoewel Liszt nooit Hongaars zou leren spreken was hij een fervent patriot, die zich verzette tegen de Oostenrijkse overheersing en zich liet inspireren door de Hongaarse volksmuziek. Soms verscheen hij zelfs op het toneel in Hongaars kostuum.

Als een speer

Zijn vader Adam was een verdienstelijk amateurpianist, die Haydns concerten had bezocht en hem ook persoonlijk had leren kennen. Toen hij eens een pianoconcert van Ferdinand Ries speelde, zong de kleine Franz de melodieën feilloos na, waarop Adam besloot hem pianoles te geven. De jongen ging als een speer en trad vanaf zijn negende op voor publiek, waarbij hij niet alleen opviel door zijn geweldige beheersing van muziek van componisten als Bach en Mozart, maar ook om zijn improvisatietalent. Zo schreef de Pressburger Zeitung in 1920: ‘Zijn spel gaat bewondering te boven en rechtvaardigt de allerhoogste verwachtingen.’

Hierna ging het snel. De familie Liszt verhuisde naar Wenen, waar Franz les kreeg van Carl Czerny. Die dwong hem alle stukken uit zijn hoofd te spelen, waardoor hij zijn leven lang de lastigste partituren à vue kon uitvoeren. Al snel groeide hij uit tot een bewonderde klavierleeuw, die in populariteit de spektakelviolist Niccolò Paganini naar de kroon stak. Niet alleen vanwege zijn geniale spel, maar ook omdat hij de uitvoeringspraktijk vernieuwde: hij plaatste zijn vleugel zijdelings op het podium, zodat de klank direct de zaal in werd geprojecteerd en het publiek zicht had op zijn watervlugge vingers. Ook ontwikkelde Liszt het ‘symfonisch gedicht’, een ééndelig orkestwerk dat een verhaal vertelt, zoals bijvoorbeeld Die Hunnenschlacht en Orpheus.

Kiemende waanzin

Maar Liszts belangrijkste wapenfeit schuilt in zijn late composities, die ontstonden nadat hij zich had laten wijden in de lagere priesterorde. Hij werd steeds ascetischer, zei het virtuoze vertoon vaarwel en ontwikkelde een taal die in zijn toenemende dissonantie vooruit wijst naar de atonaliteit van Arnold Schönberg. Zelf hechtte Liszt veel waarde aan deze stukken, maar zijn tijdgenoten deden ze af als minderwaardige producten van een aftakelende geest. Zijn schoonzoon Richard Wagner sprak zelfs van ‘kiemende waanzin’.

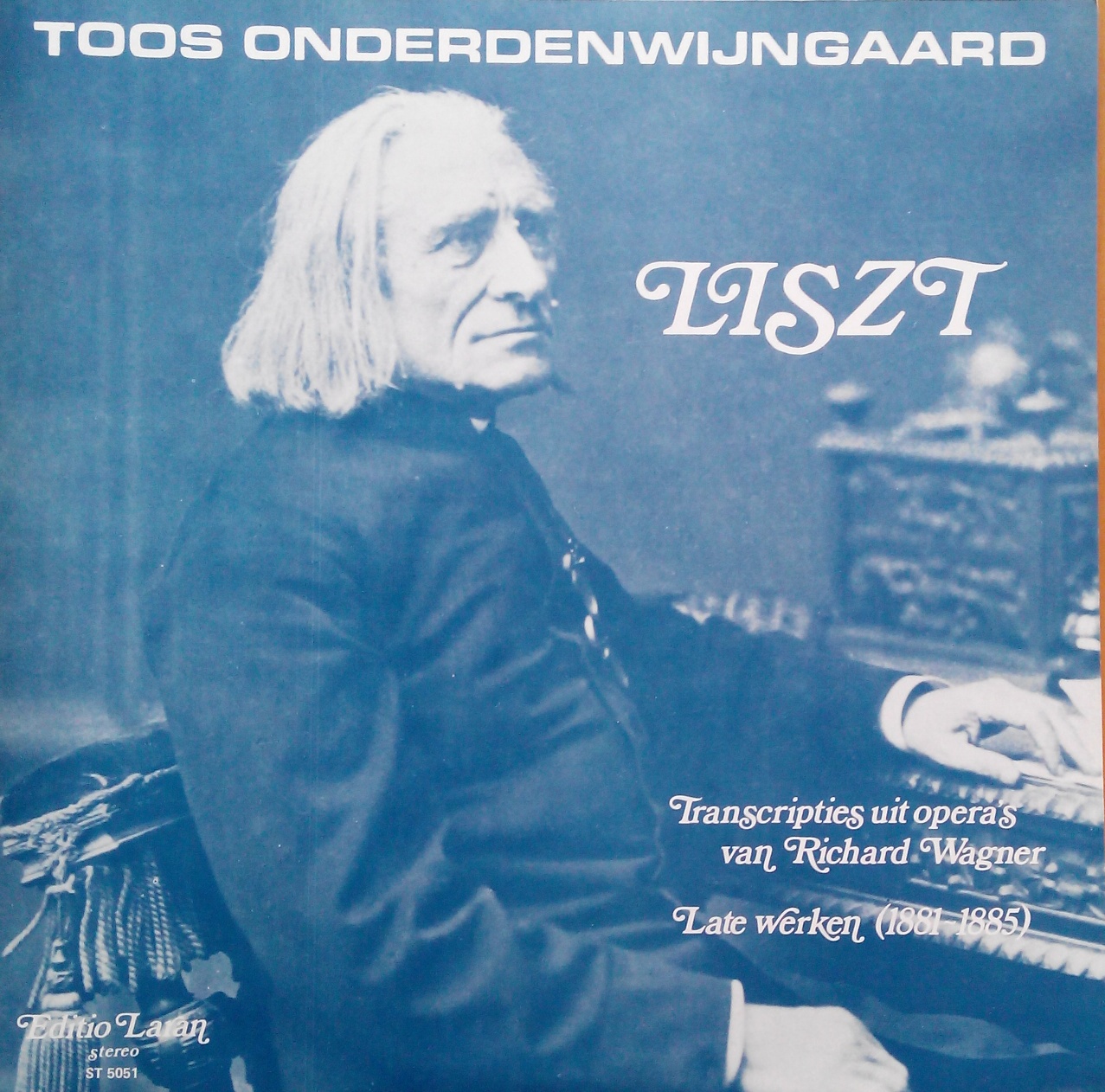

Composities als Nuages gris en Bagatelle sans tonalité bleven ongepubliceerd, tot in 1950 in Engeland de Liszt Society werd opgericht. Via crucis, zijn indrukwekkende cyclus over de kruisgang van Christus verscheen zelfs pas in 1980 in druk. In ons land behoorden Reinbert de Leeuw en Toos Onderdenwijngaard in de jaren zeventig van de vorige eeuw tot dé promotors van Liszt. In Panorama de Leeuw zoom ik hierop in, met zelden gehoorde opnames van Onderdenwijngaard en De Leeuw.

In de biografie Reinbert de Leeuw, mens of melodie ga ik diepgravend in op de opkomende waardering van Franz Liszt in ons land.