Zodra de sopraan Miah Persson het podium betreedt, horen we een harde, elektronische krak. Breekt hier een tak, een van de lievelingsklanken van componist Michel van der Aa (Oss, 1970)? Of is het toch een steen die op een ander ketst? Keien spelen een grote rol in zijn nieuwste opera Blank Out; aan het slot verpletteren zij met donderend geraas de witte Volkswagen Kever van de hoofdrolspeelster.

Van der Aa componeerde zijn op teksten van de Zuid-Afrikaanse dichteres Ingrid Jonker gebaseerde Blank Out voor het Opera Forward Festival en werd na afloop van de première op 20 maart in het Muziekgebouw aan ’t IJ hartgrondig toegejuicht. Net zoals in eerdere opera’s als One, After Life en Sunken Garden en in het celloconcert Up Close zoomt de Nederlandse multimediaspecialist opnieuw in op de relatie tussen leven en dood, tussen jong en oud, tussen hier en hiernamaals. Hij lijkt daarbij steeds dichter bij de kern te komen van wat hij wil zeggen en heeft zichzelf in deze puntgave productie overtroffen.

Blank Out vertelt het verhaal van een getraumatiseerde vrouw die ronddwaalt in het verleden, waarin ze haar zevenjarige zoontje door de golven verzwolgen zag worden. Verlamd van angst bleef ze toekijken en de rest van haar leven wordt ze verteerd door schuldgevoelens. Maar dan komt het jongetje plots tot leven – en vertelt als volwassene een heel ander verhaal: niet hij, maar zij verdronk, toen ze hem aan zijn pols uit het water trok.

De verraderlijke werking van ons geheugen is een terugkerende thematiek bij Van der Aa: niets is eenduidig en als bezoeker moet je zelf betekenis geven aan de beelden en klanken die hij je voorschotelt. Maar waar de eerdere producties nog wel eens leden onder een teveel aan interpretatiemogelijkheden, is het verhaal nu geconcentreerder, waardoor ontroering en medeleven meer kans krijgen.

[Tweet “Trouw aan zichzelf laat Van der Aa de hoofdpersoon ook dit keer zelf de scenografie bepalen”]Trouw aan zichzelf laat Van der Aa de hoofdpersoon ook dit keer zelf de scenografie bepalen en versmelten met filmbeelden in 3D. Terwijl ze grotendeels a cappella een intense klaagzang zingt om haar verloren kind, knutselt Miah Persson een boerderij in de polder in elkaar. Levensgroot zien we haar verschijnen achter het kartonnen frame en minimeubels in de kamer zetten, die door een ander camerastandpunt transformeren tot decor van haar handelingen. Zo reconstrueert ze het verleden waarin zij – en later ook haar zoon, ronddooltMet verbluffende vanzelfsprekendheid zien we haar persoon zich in tweeën en zelfs in drieën splitsten en in ‘gesprek’ gaan met zichzelf en vervolgens met haar kind (de bariton Roderick Williams), dat overigens alleen verschijnt in de film. Persson zingt haar zwierige, over alle registers uitwaaierende lijnen loepzuiver en met grote inleving en krijgt al even fraai weerwoord van Williams, die eerder figureerde in After Life en Sunken Garden. Opmerkelijk is dat hun zang niet alleen volkomen lipsynchroon, maar ook heel direct klinkt – bij Sunken Garden was het storend dat de klanken niet uit de mond van de zangers leken te komen, maar uit speakers aan weerskanten van het podium.

Naast de geweldige prestaties van Persson en Williams is er een glansrol voor het Nederlands Kamerkoor, dat op de soundtrack nu eens Renaissance-achtige polyfone klankweefsels bouwt en dan weer swingt als een gezellig barbershopkoortje. Van der Aa houdt het instrumentale aandeel klein, met lome ritmes uit dance en techno en filmmuziekachtige harmonieën die doorsneden worden met technische ‘storingen’. Deze illustreren en passant het disfunctioneren van ons geheugen.

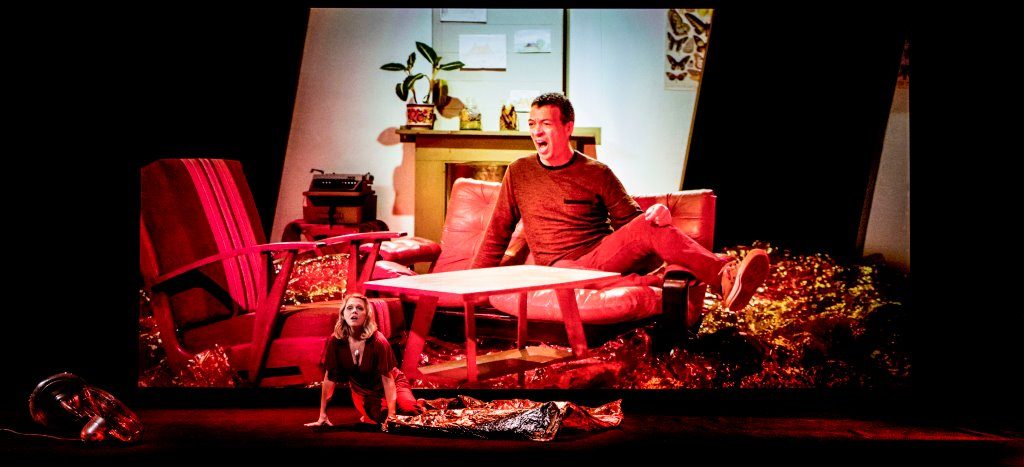

Net als in zijn eerdere producties, speelt Van der Aa een fraai spel met voor- en achtergrond, waarbij film en werkelijkheid volledig lijken samen te vallen. Zo duik je onwillekeurig weg als het stenen muurtje achter Williams explodeert en de keien recht je gezicht in lijken te vliegen. Mooi is ook het moment waarop Williams trekt aan een ‘filmrol’, die Persson óp het podium verder afrolt en naar hem teruggooit, waarop hij met een plofje terechtkomt in zijn kamer. Ronduit ontroerend is het moment waarop moeder en zoon samen ‘dansen’, nadat zij hem ‘gered’ heeft van een kolkende lavastroom – rood verlicht aluminiumfolie dat zij vanonder zijn filmbankje het podium optrekt.

Ook Van der Aa’s geliefde glazen potten ontbreken niet: Williams vult ze met verdorde bladeren van de boom bij zijn ouderlijk huis. Onthutsend is het moment waarop een arm zijn hoofd met een ruk uit een bad vol bladeren omhoogperst: de reddingsactie door zijn moeder? Daarna verdwijnt Persson van het toneel en blijven we achter met Williams en zijn rouw. Dit is het enige onbevredigende onderdeel van de opera: het duurt te lang. Met het exploderen van het muurtje is eigenlijk alles al gezegd, maar hierna volgt nog de stenenregen op de Volkswagen. Een beklemmend, Hitchcockachtig beeld weliswaar, maar het voegt weinig meer toe.

Het was ook aardiger geweest als Williams bij het slotapplaus had meegebogen vanaf zijn filmdoek. Maar dit zijn kanttekeningen bij een verder onberispelijke en meeslepende opera, waarin Van der Aa meer dan voorheen oog en oor heeft voor lyriek en emotionele zeggingskracht.

Blank Out is nog te zien op 21 en 25 maart in het Muziekgebouw aan ’t IJ. Kaarten via deze link.

Ik sprak voor Cultuurpers over het Opera Forward Festival met de countertenor Philippe Jaroussky en met de regisseur Peter Sellars, je leest het via deze link.