Een van de bijzondere voorstellingen op het Holland Festival van dit jaar is ‘Ça Ira (1): Fin de Louis’ van het Franse gezelschap Compagnie Louis Brouillard. Ik bezocht de voorstelling eerder in Luxemburg en sprak met de regisseur en schrijver van deze dik vier uur durende marathon over de Franse Revolutie. Het lijkt nogal wat: 40 acteurs op het toneel en in de zaal, en heel veel tekst, in het Frans. En dat over een historische gebeurtenis die voor moderne Nederlanders nogal ver van het bed blijkt te liggen: de Franse Revolutie.

Die relatieve onbekendheid is natuurlijk jammer: de Franse Revolutie bracht ons de moderne rechtsstaat, waarin is vastgelegd dat een meerderheid nooit zijn wil mag uitvoeren ten koste van een minderheid. Hij bracht ons ook de moderne parlementaire democratie en de scheiding tussen kerk en staat. En hij bracht ons een bezetting door de Franse legers aan het begin van de 19e eeuw.

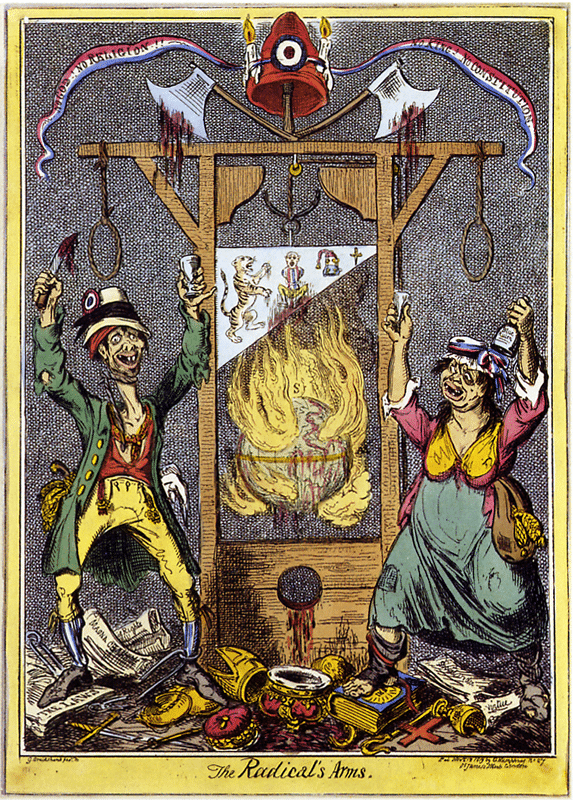

Pommerats stuk gaat over de eerste drie jaar van die Revolutie (1789-1792), de periode van de Terreur, waarin de arme bevolking wraak nam op de adel en de kerkelijke elite, en de grote steden baadden in het bloed van de duizenden onthoofdingen en plunderingen. De moderne tijd kwam niet zonder slag of stoot tot stand, zullen we maar zeggen.

Het bijzondere aan de voorstelling is wel dat er geen grote woorden en grote, herkenbare figuren in verschijnen. Ook neemt de schrijver geen stelling in. Het stuk is verrassend open en ook verrassend goed te volgen, zeker voor iemand die een paar woordjes meer Frans spreekt dan de gemiddelde deelnemer aan ‘Ik Vertrek’. Ik sprak Pommerat over zijn keuzes, de volgende ochtend.

De voorstelling is heel open in zijn mededeling: alle meningen tellen even zwaar mee. Dat geeft een verfrissende kijk op de geschiedenis.

‘Ik heb me heel lang en heel uitgebreid ingelezen: historische teksten, analyses, verslagen van gebeurtenissen tijdens de revolutie. Ik heb dat niet in mijn eentje gedaan, maar samen met de acteurs. Uiteindelijk is mijn doel om niet alleen de woorden van die periode over te brengen, maar ook de ziel van wat er gebeurde, de fysieke toestand waarin de samenleving zich bevond. De acteurs moeten die ideeën incorporeren. Ze moeten ze diep doorvoelen. Ze moeten in dialoog met de ideeën in het stuk. Daarvoor is het nodig om maanden in te lezen, maanden te praten, aantekeningen te maken. En dat begint al lang voor het schrijven van de uiteindelijke tekst.’

Ik heb geen enkele bekende naam voorbij zien komen. Geen Danton, geen Robespierre. Heeft u die uit de geschiedenis geschrapt?

‘Steeds als je een film of voorstelling ziet met historische figuren, neem je alle vooroordelen mee die je hebt gekregen door eerdere films, door eerdere boeken, door alles wat er over die mensen eerder is gezegd. Die zitten de waarheid in de weg. Je kunt niet meer goed luisteren naar wat er werkelijk werd gezegd. En zo kun je ook niet over het heden nadenken. Ik wil dat de toeschouwer toegang heeft tot de historische gebeurtenis alsof hij hem voor het eerst meemaakt. De toeschouwer moet onschuldig en vrij zijn om de woorden als nieuw te horen. Zodat hij zelf kan nadenken over wat hij hoort en ziet.

De Franse Revolutie is een historische legende, hij is inmiddels al door iedereen gebruikt om er zijn eigen boodschap mee te verkondigen. Alle politieke partijen hebben zich de Franse Revolutie toegeëigend. Zowel vroeger als nu. Hij is volledig geparasiteerd. Ik wilde de parasieten eruit hebben. Daarom heb ik de bekende namen weggehaald en er andere namen voor in de plaats gezet. Verzonnen namen.’

U kiest geen partij. Dat is ongebruikelijk voor een moderne theatermaker. Hoe vinden de critici dat?

‘Sommigen hebben geklaagd. Die kritiek gaat er dan over dat dit stuk geen partij kiest. Het velt geen oordeel over goed en fout. De tekst is geheel open voor alle getoonde gezichtspunten. Natuurlijk heb ik wel een eigen visie op de geschiedenis. Alleen: als artiest wantrouw ik mijn eigen denkbeelden. Ik twijfel over mijn gezichtspunt. Ik stel dat ter discussie. Dat is de taak van elk kunstwerk: denkbeelden ter discussie stellen. Dat wil niet zeggen dat alle gezichtspunten gelijkwaardig zijn, maar ik ben zelf ook beïnvloedbaar. Ik kan me makkelijk laten leiden door verleidelijke grote ideeën. Ik wil daarom ook heel graag de ideeën laten zien, waar ik het niet mee eens ben, en dan ook nog eens op een zo voordelig mogelijke manier. Ik geef mijn politieke vijanden eigenlijk haast meer ruimte dan mijn politieke vrienden. Dat maakt het spannender. Het is zo makkelijk om mensen met wie je het niet eens bent slecht af te beelden. Maar als het slechte ideeën zijn, worden ze niet beter door ze begrijpelijk te tonen. Het zijn nog steeds slechte ideeën, alleen beter gebracht.

Deze voorstelling kiest niet. Dit stuk is een verslag van grote gebeurtenissen, die boven de mensen uitstijgen. Het kunnen even goed Atheners zijn, of Romeinen.’

Of Europeanen. De titel ‘Ça ira’ doet denken aan de uitspraak ‘Wir schaffen das’ van Angela Merkel. Iets wat ze zei toen mensen bezwaar maakten tegen de open grenzen waar zij voorstander van was. He bleek een uitspraak die inmiddels omstreden is geraakt, en die haar mogelijk ten val kan brengen, net zoals Lodewijk, de Franse koning, zijn uitspraak ‘Ça Ira’ deed aan de vooravond van zijn eigen dood.

‘Dat klopt. In de Duitse vertaling heet dit stuk ook ‘Wir Schaffen Das’.’

Begrijpelijk, maar bent u niet bang dat het daardoor te zeer beperkt wordt tot de actuele situatie in Europa?

‘Zeker, daar was ik bang voor. Ik ging er eerst ook niet mee akkoord. Maar ik spreek slecht Duits. De vertaler, die ik zeer vertrouw, heeft me uitgelegd dat een letterlijke vertaling van ‘Ça ira’ (dat zal gaan) niet zou werken. Het is dus een compromis. Ik vind vertalingen natuurlijk altijd erg. Maar uiteindelijk heb ik er verder geen problemen over gemaakt, omdat ik me ook niet genoeg in die taal heb verdiept om erover te kunnen oordelen.’

Maar ‘ça ira’ zegt wel iets. Het zegt dat de revolutie een monster is dat – eenmaal losgelaten – niet meer in bedwang te houden is. Is dat ook uw overtuiging: dat de populistische beer los is, ook nu, en dat we sombere tijden tegemoet gaan?

‘Nee, ik ben geen pessimist. Ik denk ook niet dat ik meer weet over hoe het met de wereld zal gaan, dan welke andere wereldburger ook. Ik weet niet alles. Ik ben maar een poppetje, een acteur. Ik zing een liedje mee. Dit is maar één van de mogelijke gedichten die er te schrijven zijn. Ik kan niet zeggen dat ik over speciale kennis beschik waarmee ik de toekomst beter kan duiden dan iemand anders. De vraag of ik optimistisch of pessimistisch ben, is totaal onbelangrijk. Het gaat er in deze voorstelling over of ik het goed of slecht vertel. Ik wil het goed vertellen.’

Dat is een bijna journalistieke aanpak.

‘Niet echt. Een journalist gelooft namelijk in objectiviteit. Ik geloof niet in objectiviteit. Ik heb een verhaal te vertellen. Meer niet. Ik reconstrueer.’

Maar van een kunstenaar mag toch verwacht worden dat hij een duidelijk standpunt heeft?

‘Dat is inderdaad wat in alle kunstopleidingen wordt onderwezen: wees artiest. Wees uzelf. Wees uniek. Geef een uniek commentaar op de samenleving. Maar vandaag de dag heeft iedereen een mening. En die is ook nog eens uniek. Welk belang heeft dat in artistiek opzicht? Het is natuurlijk goed dat iedereen zichzelf kan profileren, maar wat is het speciale belang van de kunstenaar dat zijn commentaar en zijn opinie belangrijker zou zijn dan die van een ander? In een echte democratie zoals die van nu, is een kunstenaar niet belangrijker dan iemand anders. Het is geen aristocraat, hij staat niet boven de rest. Waarom moeten we naar hem kijken? Hij moet zijn werk doen zoals iedereen.’

Dat is best een revolutionaire uitspraak.

‘Ik denk dat een heel oud idee is. Het is ooit verlaten, maar ik vind het steeds belangrijker worden. Het oude kan weer modern worden. Dit bewustzijn van de bescheiden kunstenaar is belangrijk voor nu.’

Deel 1 van uw stuk loopt tot 1791. deel 2 zal tot 1794 doorlopen. Dus tot het einde van de periode van ‘De Terreur’. De periode van de massamoord op de adel en de kerk. Dat vertoont alleen op het woord al overeenkomsten met de huidige periode, nu Parijs twee grote aanslagen achter de rug heeft: Het stuk kwam uit na de aanslag op Charlie Hebdo, maar voor de Bataclan-aanval. Hoe werkt dat voor u?

‘Ik merk dat dit stuk erin slaagt om een jongere generatie bewust te maken van de geschiedenis. Opnieuw beleven we nu een periode waarin de emoties collectief gevoeld worden, net als toen. Feitelijk zijn het nu de ideale omstandigheden om dit stuk te spelen. Hoe erg het ook is om dat te zeggen.’

De geschiedenis herhaalt zich.

‘Dat is het banale idee, maar ik vind dat niet zo interessant om dat in relatie tot dit stuk te concluderen. Dingen mogen zich dan wel herhalen, maar het gebeurt ook steeds op een andere manier. En we hebben wel degelijk een vrije wil waarmee we dingen kunnen veranderen. Ik ben geen pessimist of defaitist. Ik geloof in de verantwoordelijkheid van de mensen. Het collectief kan wel degelijk iets goeds veroorzaken.’

Ça Ira?

‘Ça Ira.’