Zaterdag 4 juni 2016 was ik aanwezig bij de koninklijke opening van het Holland Festival en ik kon er geen recensie over schrijven, want ik zat op de voorste rij van de Amsterdamse Stadsschouwburg. Omdat het podium verhoogd was, keek ik tegen een zwarte muur aan, waarboven alleen de voorste acteurs zichtbaar waren. De achterste en onderste helft van het toneelbeeld waren mij volledig ontgaan.

Ik schreef dat op, en het Holland Festival stelde mij ruimhartig in de gelegenheid om de voorstelling nog een keer te gaan zien, vanaf een betere plek. Tegelijk vertelde de organisatie dat de eerste drie rijen van de Stadsschouwburg bij deze voorstelling zouden worden gecompenseerd. Ik ging dus nog een keer naar Amsterdam, op maandag 6 juni.

Voorafgaand aan de voorstelling, tijdens het niet eten van een zwartverbrande hamburger in schouwburgrestaurant Stanislavski, hoorde ik van de keurige mensen aan het tafeltje naast mij dat de voorste stoelen tegen scherp gereduceerd tarief werden aangeboden, en dat mensen zoals zij die al een kaartje hadden gekocht de keuze hadden om dus een deel van het geld terug te krijgen of op de wachtlijst te gaan staan voor een plek met betere zichtlijnen. Of het hun uiteindelijk gelukt is een van de plekken met beter zicht te bemachtigen, weet ik niet. De voorstelling zat vol, tot en met die eerste rijen met hun beroerde zicht.

Hoe zat het nu met die verhoging?

Amsterdam is de laatste theaterzaal in Nederland waar de toneelvloer 10 graden richting de zaal helt. In alle oude theaters was dit gebruikelijk om zo het publiek in de vlak liggende stalles toch nog een beetje zicht op het hele toneel te bieden. Met de opkomst van het reizende toneel, in de loop van de twintigste eeuw, zijn alle nog overgebleven hellende toneelvloeren rechtgetrokken, omdat het voor decorbouwers onmogelijk was om een decor te bouwen dat geschikt was voor al die gradueel verschillende hellingshoeken.

Behalve dus in Amsterdam, omdat, nou ja, Amsterdam Amsterdam is en de zichtlijnen voor de stalles niet op een andere manier konden worden verbeterd.

Dat dat tot ellende kan leiden heb ik in 1991 aan den lijve kunnen ondervinden, toen ik regie-assistent was bij de tournee van Beckett’s Eindspel van Het Zuidelijk Toneel. In die voorstelling zit een personage (Hamm) op een rijdende stoel. In dit geval kon de acteur (Bert André) ook niet met zijn voeten bij de grond om de stoel op zijn plek te houden. Dat was ook nergens nodig, behalve, uitgerekend, in Amsterdam. Een half uur voor aanvang van de voorstelling in Amsterdam hadden de technici een rem op de stoel gemonteerd, die door het andere personage (Clov) bediend kon worden. Deze rem brak af tijdens de eerste handeling die Hans Kesting met de rolstoel deed. Hij is daarna anderhalf uur nauwelijks aan acteren toegekomen. Hij was uitsluitend bezig om te voorkomen dat Bert André van het hellende toneel af zou rijden, de eerste rij tegemoet.

Waarom deze uitleg? Welaan: het moge duidelijk zijn dat autonome decorstukken op wielen zich slecht gedragen op een hellende schouwburgvloer. En in Die Stunde Da Wir Nichts Voneinander Wussten staat een 12 meter brede, 6 meter hoge wand op het toneel. Op wieltjes. Daar zet je dus geen simpel remmetje op. Ik hoorde dat technici van de schouwburg en het bezoekende gezelschap sinds woensdag 1 juni bezig zijn geweest om de vloer waterpas te maken. Met dus die desastreuze gevolgen voor de eerste drie rijen.

Was het stuk nu beter te genieten?

Ik was door de organisatie nu op een plaats gezet naast de koninklijke loge op het eerste balkon van de Stadsschouwburg. Veel beter dan dat is er in Amsterdam niet te krijgen. Ik had perfect zicht op de kijkkast die het toneel in deze historische schouwburg is, en in die kijkkast zag ik inderdaad hoe mooi de Estse regisseurs het stuk in beeld hadden gezet. Het overzicht dat ik nu had zorgde voor een veel grotere impact van het getoonde, wat vooral werkte bij de massale, verstilde choreografieën, die gelukkig ruim voorhanden waren. En die inderdaad het hele toneel besloegen, iets wat ik tijdens mijn eerste bezoek alleen maar had kunnen vermoeden.

Bleef overeind dat de scenes die door het regieduo aan Peter Handkes origineel waren toegevoegd nog steeds uitblonken in overbodigheid. Wat door de auteur ooit bedoeld was als scripted reality verwerd hierdoor tot een nogal platte revue, een dance macabre van Europese geschiedenisfeiten en koddige verwijzingen naar de actualiteit: Sinterklaas en Zwarte Piet, vluchtelingen, terroristen, en uiteindelijk de Chinezen die de plaats innemen van de tot carnavalsfiguren verworden vergrijsde westerse mens: met Mickey Mouse als hoofdgast.

Ook vanaf het eerste balkon werkte de gregoriaanse zang overigens perfect.

Blijft de vraag waarom een stuk dat het zo van die gefocuste blik moet hebben in zo’n zaal getoond wordt. Ook de premièrezaal in Hamburg heeft de hoefijzervorm met platte stalles die in Amsterdam voor zulke slechte zichtlijnen zorgt: toeschouwers op de zijbalkons zien vooral zich haastig omkledende acteurs, wat afleidt van het plaatje op het toneel. De makers lijken op de koop toe te nemen dat alleen kopers van de middelste stoelen zien wat zij ook zien.

Wat moeten we nou met die schouwburg?

De halfronde schouwburgzaal, met zijn al dan niet scheve vloer, ook wel ‘bonbonnière’ genoemd, is ontstaan in de negentiende eeuw. Hij was een voortzetting van de barokzalen uit de tijd van de grote monarchieën in Europa: zalen waarbij het toneel feitelijk bijzaak was, en men vooral kwam om te kijken naar elkaar en om gezien te worden. Eigenlijk waren die theaters, waar koning, koningin en andere notabelen niet eens in een koninklijke loge zaten, maar vanaf een plek naast de toneelspelers de zaal in keken, een soort massale selfiesticks avant-la-lettre.

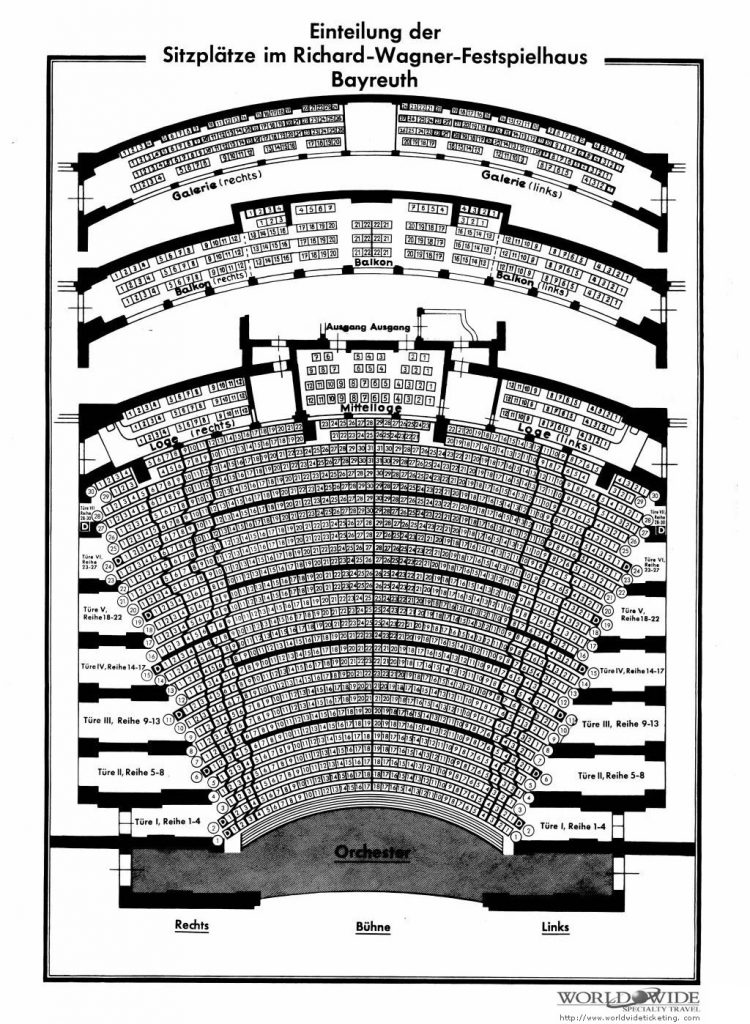

De eerste die zich echt bekommerde om de zichtlijnen voor het publiek was Richard Wagner, die met zijn opera’s een totaalervaring wilde bereiken, waarbij iedereen in de zaal perfect uitzicht had op de perfecte illusie: hij bouwde speciaal voor zijn Gesammtkunstwerke een theater zonder koninklijke loges, zonder praalzetels, maar met perfecte zichtlijnen voor iedereen: totale onderdompeling.

Korte tijd daarna werd de bioscoop uitgevonden, die dit alles dankzij de film voor een veel lagere prijs wist te realiseren.

Overal in Europa staan nu echter nog van die schouwburgzalen met die best mooie, monumentale vormgeving, waarbij de kunstenaars die er voorstellingen maken, samen met het publiek al de afspraak hebben dat er eigenlijk maar een paar stoelen zijn vanwaar je goed zicht hebt op de handeling.

Steeds vaker verzetten makers zich tegen die strakke vormeis, en feitelijk ondemocratische zichtlijnenterreur. Ze breken ‘uit de lijst’, zoals Ivo van Hove regelmatig doet, maken ‘toneel op toneel’ of ze keren zich helemaal af van die historische gebouwen, om op locatie of in modernere zalen te gaan spelen.

En nieuw publiek dat voor het eerst in zo’n zaal met zijn beroerde zichtlijnen komt, raakt maar moeilijk overtuigd van de noodzaak om vaker naar zo’n verouderd gebouw te komen.

Het alternatief: trek het podium door, de zaal in.

Toneelgroep Amsterdam heeft het al een keer gedaan, voor ‘A perfect wedding’: de stoelen uit de stalles weghalen en podium gewoon doortrekken de zaal in. Hetzelfde deed de legendarische toneelvernieuwer Peter Brook met het oude boulevardtheater dat hij in Parijs bezit, Les Bouffes du Nord. Ook die zaal is verhoogd, en het is een genot om er vlakbij de acteurs, op gelijk niveau, hun verhalen te beleven. Het betekent feitelijk een terugkeer naar het Shakespeareaanse theaterontwerp: wie in Londen het herbouwde Globe Theatre bezoekt, snapt opeens waarom Shakespeare’s stukken gefluisterd kunnen worden in een zaal die ruimte biedt aan 2000 toeschouwers (twee keer zo groot als de Amsterdamse Stadsschouwburg): het toneel staat hoog midden in de zaal, waardoor zelfs iemand op de achterste rij van het bovenste balkon niet verder dan een meter of zes van de acteurs verwijderd is. Kom daar maar eens om in een normale schouwburg.