This month, early music pioneer Marijke Ferguson turned 89. She led the adventurous ensemble Studio Laren for 30 years and has been making radio for over 50 years, the last 23 for the Concertzender. Time and again, she manages to intertwine old and new music with pop and world music in an appealing way. On Sunday 11 December, the Concertzender will put her centre stage during a live recorded radio broadcast in the Public Library of Amsterdam. I spoke to Marijke Ferguson at length in 1995 for my doctoral thesis in musicology, below is a summary.

'Recorder is not an instrument, is it?'

Ferguson (born Buitenzorg, 1927) grew up in Indonesia, where she was taught piano by her mother. During the war, she ends up in a Japanese prison camp, where she has the suling learns to play, an Indonesian flute. 'I had my heart set on that instrument. When I came to the Netherlands after the war, I decided to take lessons on the recorder. At the time, that was only possible with Kees Otten, who taught clarinet at the Muzieklyceum in Amsterdam. When I wanted to register with him, the administrator initially refused to take me on. The recorder wasn't an instrument, was it? I was better off learning to play the oboe.' - Ferguson got her lessons and would later be principal subject recorder teacher at the conservatory for 30 years.

'Because of the war, I didn't go to secondary school, but for the recorder and later the small harp I did receive thorough training. I also did courses with Gustav Leonhardt, for example on ornamental techniques. My work for radio and thinking and writing about music gave me a lot of musicological work to do, although I was not trained for that. I was reproached for that by professional musicologists.'

Kees Otten played on authentic instruments. 'That's why I became so fascinated by it. We were striving to get the recorder accepted professionally. Kees had been taught by his uncle Willem van Warmerloo, who wrote a recorder method which I still admire. He based himself on old and even ethnic melodies, which was incredibly progressive just after the war. There was a favourable climate for early music and we contributed ours. It was fantastic to discover everything. Rutger Schouten of VARA, for instance, programmed Jephte by Carissimi, that hit like a bomb!'

Amsterdams Blokfluit Ensemble with very young Frans Brüggen

They draw their repertoire from a trio of anthologies published in Germany. Together with Frans Douwes and Frans Brüggen, they founded the Amsterdam Recorder Ensemble in the late 1940s. Brüggen is a pupil of Otten's and is still in secondary school. 'We were the first recorder quartet in the Netherlands and gave school concerts throughout the country. If Frans couldn't, we played trio, we were all about the closed recorder sound.'

'Since we felt that an instrument only becomes healthy and alive if it is also rooted in its own time, we performed contemporary music alongside works by Lassus, Dowland or Gastoldi, for example. We commissioned and eagerly followed the concerts that Daniel Ruyneman at the Stedelijk Museum. Moreover, we campaigned for affordable editions of contemporary recorder literature. We held talks up to the department to get the recorder accepted as a principal subject. And we succeeded!

Obrecht Music Circle

When Safford Cape came to the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam with his early music ensemble in 1951, a spark struck Ferguson. 'They worked with voice, lute, fiddles and recorders and played Dufay and Machaut so beautifully, we could never approach that with our recorders. During the break, I sighed to Rachel Mengelberg that if I could get my hands on a small harp, we could start making music like that too. Coincidentally, she knew that a copy had just been made of a harp in The Hague's Gemeentemuseum. I bought that the next day.'

Together with Kees Otten, to whom she is now married, she founded Muziekkring Obrecht, which focuses exclusively on early music: 'With that ensemble, we didn't feel the need to play new work, we were all about performing those old compositions. There were three couples of us. Joannes Collette played the viola and lute in addition to recorder. His wife Folly sang. Hans van den Hombergh did choral conducting, his wife Antoinette played the violin. Sometimes singers from the Nederlands Kamerkoor joined in. We worked like this for ten years and tracked down an extraordinary amount of repertoire.' In 1961, when Kees and Marijke's marriage foundered, the group disbanded.

Ferguson moves with her two children to Laren, where she moves into 'a kind of chicken coop' and teaches at the Montessori school. 'I needed to earn money and become economically tied to Laren so I could get a decent house.' She also teaches at the Sweelinck Conservatory in Amsterdam and the Middeloo institute in Amersfoort. She decides to continue in music under her maiden name.

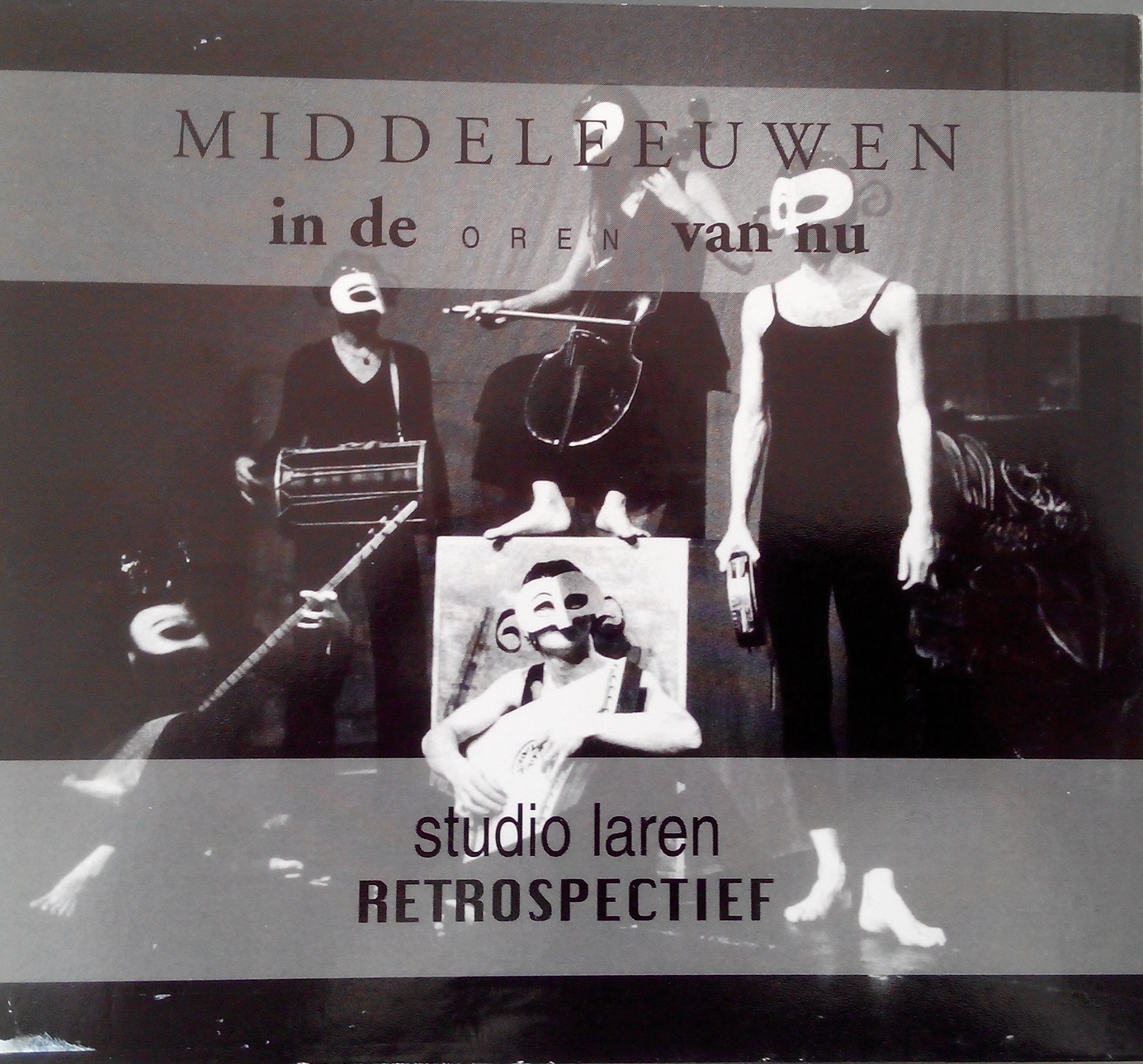

Studio Laren

Soon she was asked by Ab van Eyk of the NCRV to make music for radio plays. 'Cultural historian G.C. Rijnsdorp designed a series on the development of the history of mentality from the ancient Greeks to the Enlightenment, under the title Adam, who art thou?. He had the progressive idea of adding music from the relevant periods. He came up with texts and I looked for pieces to go with them. This made me realise that there is a relationship between all the cultural expressions of a certain period. I decided to set up an ensemble in which the combination of these different aspects would be central. That became Studio Laren.'

Studio Laren's first production In tilting time premieres at the Singing Attic in The Hague on 21 March 1965. In it, Ferguson puts the renaissance centre stage. She creates an "interplay" of text, image and music. Four speaking voices perform fragments of prose and poetry from Petrarch, Savonarola, Luther and Erasmus, among others. Meanwhile, film footage is shown and slides are projected showing works by Michelangelo. There is also a sound montage. The whole event is larded with live music performed by Josquin, Tromboncino and anonymous masters.

Audiences come in large numbers and react with rapturous enthusiasm - reactions in the press range from extremely positive to benevolently critical. A more frequent complaint is that the quality of performance leaves much to be desired. Ferguson: 'I have encountered that problem throughout my career. If you keep coming up with new things, you have to reinvent the wheel every time. If you sing Schubert, you put on a dinner jacket or a nice dress, stand in the curve of the grand piano and sing your song as best you can, that form of presentation has been consolidated over the years.'

New challenges

'We were always faced with the question: how do we bring something? For example, I was the first to give a concert in the Noorderkerk in Amsterdam. A round church. I had planned three performances, which the audience could attend in stages. No one had ever done that, now it's quite common. I wanted to welcome the audience with fanfares by Josquin, the musicians would accompany people to their seats while playing. It was already difficult enough to find musicians who could perform this music, but bringing the audience along proved even more problematic. The press only sees that first performance, while the second and third are much better.'

The obvious option of concentrating on a particular form and working it out to perfection has never appealed to her. 'For once, it is in my character to want to do new things all the time. I am interested in experimentation, research. By the way, the music-making itself I did work out, it's just that the presentation was not always strong, that was a journey of discovery each time.'

Public participation

What Ferguson also developed were dance courses at the Shaffy Theatre. 'My basic idea in everything is that you learn by doing. That's the only way you get answers to questions you encounter along the way. I was once leafing through a booklet by musicologist Julia Sutton on old dance forms in a shop when Conrad van de Wetering, a dancer, came in. He told me he had helped her understand the steps described. I said: then you are my man! A month later, we had a course at the Shaffy. We did that for four years, every Monday evening. Then it was taken over by others.'

She never had to complain about audience interest. Her radio programmes, first The musical cabinet at the NCRV, later Music from the Middle Ages and Renaissance at NOS, were hugely popular and also gave her the opportunity to attract audiences to her performances. How well her broadcasts were listened to and appreciated was evident when she made an appeal to her listeners to come and play music in Hilversum.

'On my quests, I came across a lot of repertoire for larger ensembles, for example double-choir music from the time of Praetorius. I could never (have) heard those because there were only small ensembles for early music. We were overwhelmed with applications! With Edu Verhulst, the man in charge at NOS, I then decided to organise a concert day. We selected 185 people, from eight to eighty and from amateur to professional. It was a resounding success!'

New initiatives are becoming commonplace

Although Ferguson has a large and loyal audience of her own to this day, she was never fully accepted in the music world. Especially among musicologists, there was a lot of naivety about her radio programmes. 'They felt that a programme on early music should be made by a trained musicologist. Fortunately, Edu Verhulst was always right behind me.'

The search for ever new forms of expression also appears to have more drawbacks than a sometimes sceptical press. Subsidisers do not always know what to do with Studio Laren and reluctantly give money. Another disadvantage is, that what Ferguson develops by trial and error, is a few years later brought as 'new' by someone else and applauded by press and music world.

Besides the dance courses in early music, this is also true of the storytelling cellar Brandaan, which Ferguson set up in 1988. An actor or actress tells stories from a particular period while the listeners are regaled with food and drink from the same era. It has since become a popular phenomenon, but Ferguson had to fight for subsidies at the time. Piqued, she noted in 1995 that although Stad Amsterdam eventually supported her, it did so for the wrong reason. 'Their understanding of a literary evening does not extend beyond an author reading their own work, they give a location subsidy because I rehearse here with Studio Laren.'

Meanwhile, both Studio Laren and Story Cellar Brandaan are defunct, but Ferguson still presents the weekly Radio Music essay on the Concertzender and once a month makes the programme Antiqua versus Nova.

On her 89e Marijke Ferguson still has ears on stalks and continues to tantalise us with unusual music and unexpected connections.

More information and register for 'Ears on stalks' on Sunday 11 via this link.