Godfried Bomans stierf een halve eeuw terug. Bijna meteen daarna verzonk Nederlands meest geliefde schrijver in de vergetelheid. Het is tijd voor een herwaardering van Bomans’ literaire werk én zelfs zijn politieke standpunten. Ik dook in de archieven, tevens speurend naar de schaarse sporen van Bomans in Amersfoort.

Eerst een paar ronde getallen. Hij verzorgde zeventig jaar terug een lezing in Amersfoort die in het stoffige stadje voor enige opwinding zorgde. Daarna kwam hij alleen nog naar Amersfoort als verslaggever: vijftig jaar geleden zat hij aan de kant bij een verkiezingsbijeenkomst van D66. Later dat jaar – dus ook een halve eeuw terug – ging hij dood. Hij werd slechts 58, net als zijn grote voorbeeld Charles Dickens.

Dat overlijden wierp een lange, duistere schaduw over het land. Bomans was destijds Nederlands meest geliefde schrijver én meest geliefde tv-persoonlijkheid. Mensen reageerden alsof een dierbaar familielid was overleden. De uitvaart werd massaal bijgewoond.

Vergetelheid

Bijna direct daarna zette de vergetelheid in. Opeens was Bomans een rechtse bal, een ouderwetse katholiek, een zelfingenomen kwal, iemand die niet de taal sprak van de huidige tijd. In zijn laatste levensjaren ‘lag’ hij toch al minder goed bij de Volkskrant, waar zijn column van de zaterdagse voorpagina verdween. Wie durfde te bekennen dat hij of zij hem las, moest zich uitputten in verontschuldigingen.

Mijn vader Wim de Valk, vanaf 1958 collega bij de Volkskrant, was wat ambivalent. Enerzijds vond hij dat Bomans de tijdgeest niet meer begreep. Ook was hij als nuchtere Rotterdammer wars van de heldenverering die de schrijver lange tijd ten deel viel. Anderzijds verzamelde hij die columns in schriftjes: uitgeknipt en ingeplakt. Zo bespaarde hij met naoorlogse zuinigheid de kosten van de bundels, die met enige regelmaat uitkwamen.

‘Luxeverslaggever’

Ik was 16 jaar en we schrijven 1974 toen ik al het in de Diemense bibliotheek beschikbare werk van Bomans had gelezen en aan het herlezen daarvan was begonnen. De boeken mochten niet op de leeslijst van de mavo, wat ‘Bomans is geen literatuur’. In die tijd drong het geleidelijk tot mij door dat ik hem een paar keer had aanschouwd. Als jochie mocht ik wel eens mee naar de toenmalige redactielokalen van de Volkskrant aan de Nieuwezijds Voorburgwal.

Mijn vader draaide dan een zondagsdienst te midden van grijze bureaus, grote typmachines en volle asbakken. Zo werd mijn moeder ’s middags even ontlast. Ik ging tekeningen maken of probeerde een Brief aan mama te schrijven, waarbij ik soms boos werd omdat ik ondanks eindeloos speuren de rrr of de ggg niet kon vinden. Dan kwam papa even helpen, want die wist waar élke letter zat. Als het wat later werd, waren er opeens overal flesjes bier en bulderend lachende mannen.

Soms kwam een meneer met warrige haren binnen scharrelen van wie zelfs een ukkie als ik kon zien dat hij bijzonder lang was. Die ging ergens in een hoekje zitten – ik meen op een vensterbank – en krabbelde met een krullerig handschrift wat op een notitieblok. Hij rookte een pijp of haastig geïnhaleerde sigaretjes. De uitgescheurde velletjes papier overhandigde hij aan een van de andere meneren, hij mompelde wat met diepe stem en vertrok. Later begreep ik dat iemand zijn column voor hem zou uittypen. Meneer Bomans behoorde tot de medewerkers die dat handwerk aan anderen overlieten. Mijn vader had het niet zo op ‘luxeverslaggevers’; die maakten goede sier voor de buitenwereld maar konden slechts bestaan dankzij het gedisciplineerde voetvolk.

Schrijf- en lezingenfabriek

Terug naar Amersfoort, sinds 34 jaar mijn woonplaats. Bomans kwam daar dus maar zelden. Dat is merkwaardig, want hij trok door heel het land. Zijn ‘lezingen’ – meestal humoristische conferences – waren razend populair. Sla het ‘Dagboek 1957’ er maar op na; er waren weken dat hij elke dag ergens optrad, in allerlei uithoeken van het land. Hij nam dan meestal de trein, die nog lang niet zo snel ging als tegenwoordig. Daarnaast scheef hij zich in zijn werkkamer drie slagen in de rondte. Hoewel hij de mythe voedde dat hij ‘lui’ was, moet de werkelijke Bomans worden beschouwd als een schrijf- en lezingenfabriek. Zijn verzamelde werken bestaan uit zeven delen á ruim achthonderd pagina’s.

Waarom kwam de katholieke schrijver zo weinig in Amersfoort? Dat kan iets met de verzuilde maatschappij te maken hebben. (Thuis merkten we daar alles van. Mijn vader werkte eerst voor de RK Maasbode in Rotterdam en toen voor de RK Volkskrant in Amsterdam. Hij vond een woning in Amsterdam dankzij een RK wooncorporatie en het hele gezin ging er naar de RK kerk.) Bomans werd gretig uitgenodigd door genootschappen in grote steden, waar altijd wel katholieken te vinden waren. Hij was bijzonder gehecht aan typisch Roomse steden als Nijmegen. Maar Amersfoort was overwegend protestant. Het nabij gelegen Hoogland was katholiek, maar voor zo’n dorp kwam hij niet helemaal vanuit Haarlem met de trein. Ook was Amersfoort in zijn tijd nog lang niet de cultuurstad die het zou worden.

Recreatie en Algemene Ontwikkeling

Maar hij wás er, op donderdagavond 8 februari 1971. Hij sprak in Amiticia, één van de twee schouwburgen in de stad. De andere was het Grand Theatre, even verderop. Dat fungeerde ook wel als bioscoop, maar op deze avond concerteerde daar het Utrechts Symfonie Orkest. Verder kende de stad nog twee kleine bioscopen. Het gebouw Amicitia dateerde van 1837 en lag aan Plantsoen Zuid: een deel van de idyllische, groene gordel om de oude stad. Met een beekje, een muziekprieeltje en rustieke villa’s. Nu raast hier het verkeer door de Stadsring. Achter en onder de gevel van weleer is nu een zieltogend winkelcentrum gevestigd. Amersfoorters spreken meewarig van ‘de koopgoot’.

We mogen aannemen dat meneer Bomans werd afgehaald van het station, een paar honderd meter verderop, door nerveuze mannen van het comité. Zijn lezing startte om 20.00 uur. Hij was uitgenodigd door officieren van de R.A.O., ofwel de afdeling Recreatie en Algemene Ontwikkeling van het in Amersfoort gelegerde garnizoen. Het Dagblad voor Amersfoort schreef in 1946 dat de afdeling waakte over ‘de ontwikkeling en ontspanning van den Nederlandschen soldaat’. ,,De soldaat moet een kerel worden, die straks in de maatschappij zijn plaats kan innemen, die er een volwaardig lid van wordt, ondanks de jaren, die hij in het leger doorbracht.’’

350 woorden

Bomans sprak voor de Geneeskundige Troepen. Die zullen vooral hebben gewerkt in het Militair Hospitaal aan de Hogeweg. Een verslaggever van de genoemde krant repte zich na afloop naar de redactieburelen, die gelukkig slechts honderd meter verderop waren gelegen. Aan de Snouckaertlaan typte hij een verslag van zo’n 350 woorden; kort voor die tijd, want krantenartikelen konden eindeloos lang zijn. Waarschijnlijk was de pagina al gezet en had de opmaker dit hoekje voor de anonieme verslaggever nog even vrij gehouden.

Opvallend is, dat het parool ‘show, don’t tell’ nog geen gemeengoed was geworden in 1951. Tegenwoordig leert iedere journalist dat het onbevredigend is om een spreker ‘humoristisch’ te noemen. (Het woord klinkt op zich al archaïsch.) Beter kun je illustreren waaruit die geestigheid blijkt. Dat laatste doet de verslaggever niet. Bomans ‘las voor uit eigen werken op onnavolgbaar pikante en humoristische wijze’, de avond ‘muntte vooral uit door een grote dosis humor’ en de auteur sprak ‘bijzonder geestig’ over zijn jeugd. Hoe hij dat deed, komen we niet te weten.

Off. van Gezondheid Overste dr. H.M. v.d. Vegt

Tussen de regels door merken we wel dat de journalist de hete adem van de autoriteiten in zijn nek voelde. Hoge militairen verwachtten dat ze werden genoemd in zo’n verslag. Veel andere media waren er niet, en de pers was gedwee en gezagsgetrouw. We lezen dus dat ‘Vaandrig Schol’ de avond opende en dat vele officieren van hun belangstelling blijk gaven, met name ‘de Commandant van het Rgt. Geneeskundige troepen, de Off. van Gezondheid Overste dr. H.M. v.d. Vegt’. De redactiechef had misschien anders de volgende ochtend een boze officier aan de telefoon gekregen.

Dan de inhoud van de avond. De ‘lezingen’ van Bomans waren half ernstige, half geestige causerieën waarin hij werkte als een jazzmuzikant: improviseren met bekend materiaal als houvast, in een constante wisselwerking met de omgeving. Vroeg een toehoorder om een specifiek advies, dan bedacht hij ter plekke een Oom die wonderlijke dingen had meegemaakt, met als moraal: het antwoord op de vraag. Later in de jaren ’50 had hij een radio-serie: ‘Problemen verdwijnen waar de Kopstukken verschijnen’. Na de vraag van een bemiddelde mevrouw of ze moest sparen of juist niet, kwam hij met een Oom die elke avond zijn geld telde; de man kwam nergens anders meer aan toe. Totdat na vele jaren op dezelfde stoel een notaris zat, die sprak: ,,Nou mevrouw, het is een mooi bedrag. En van harte gecondoleerd.’’ Welke lering trekken we hieruit? Juist.

Boert en jokkernij

Hij sprak met een ingetogen maar ver dragende stem. Langzaam naar de huidige maatstaven. Zijn betogen waren doorspekt met talloze archaïsmen als ‘derhalve’, ‘boert en jokkernij’ en ‘het zwerk’. De enige professionele schrijver die zich daar anno 2021 nog van bedient, is Jean Pierre Rawie, in zijn wekelijkse columns voor het Dagblad van het Noorden. Zijn oo’s en aa’s gingen gepaard met een licht bekakt accent. Zijn kritiek was vrijwel altijd mild, wie of wat het ook betrof. Evenals Toon Hermans wekte hij de indruk maar wat te improviseren, en dat deze avond wel héél bijzonder was. Hermans ging daarbij zover om zijn show op te dragen aan Oom Sjeng of Oom Twan, aangezien deze beminde overledene vandaag jarig zou zijn. Ook Hermans grossierde in familieleden. Zo ver ging Bomans niet.

In Amersfoort begon de veelgevraagde spreker met de vaststelling dat hij maar ‘gewoon’ wat ging voorlezen, want uit het hoofd voordragen was een kunst die hij niet meester was. Daarna volgden tweeënhalf uur waarbij het publiek aan zijn lippen hing en die werden bekroond met een ‘langdurig applaus door de geheel gevulde zaal’.

Ajax-Atletico

Hij sprak volgens het Dagblad onder meer over ‘Erik of het klein insectenboek’, zijn sprookjesachtige succesroman uit 1941. Hij putte hierin ‘uit jeugdherinneringen, terugdenkend aan een verloren paradijs, waarin de ouder wordende mens nimmer zal terugkeren’. De hoofdpersoon Erik ‘kon zich met zijn bestaan niet verenigen’ en verdween dus ’s nachts in de wondere wereld van het schilderij Wollewei. Het boek bevatte ‘talrijke satires’ en ‘grote en kleine wijsheden’.

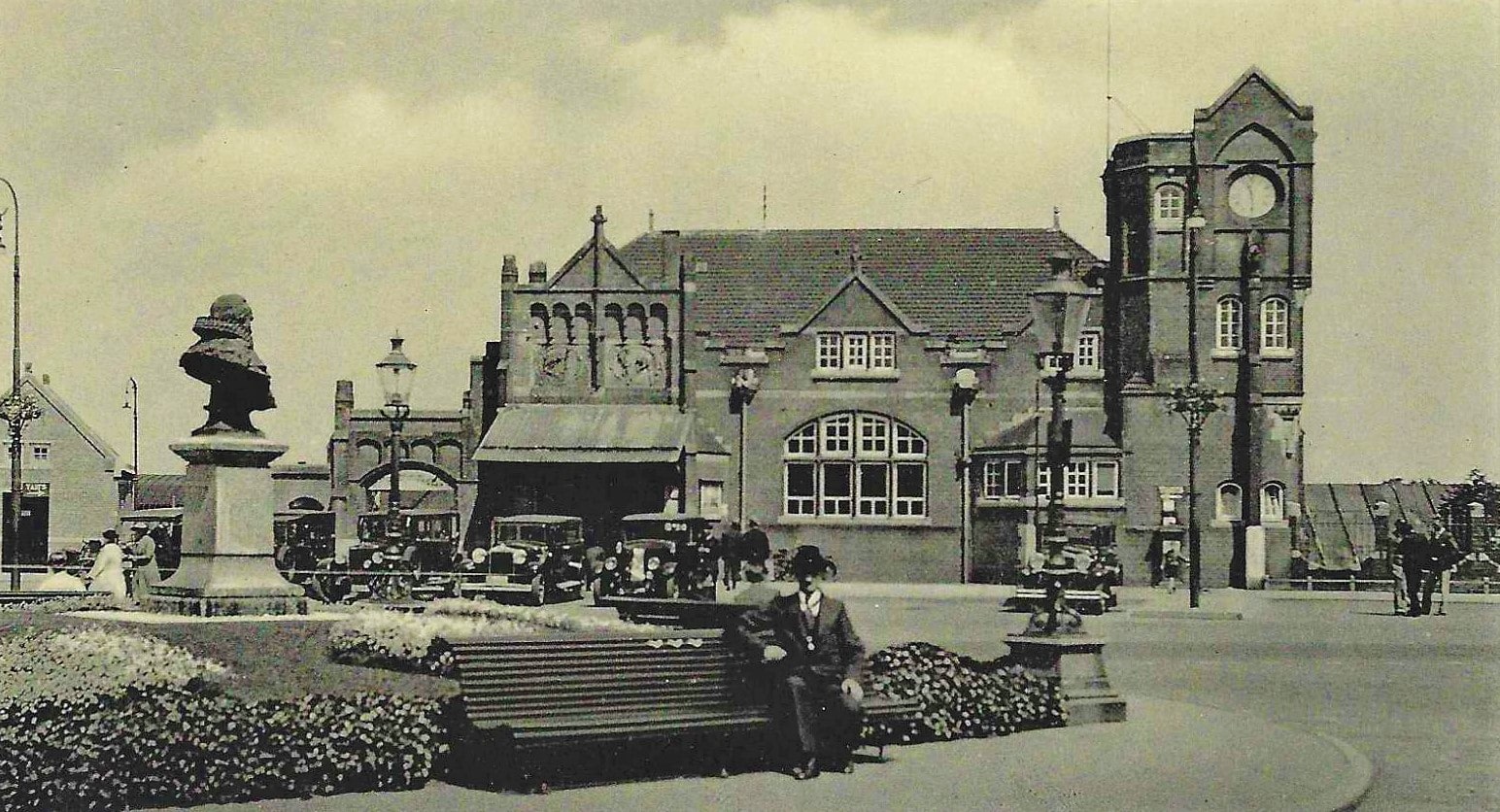

Na vermoedelijk nog een borrel-na met de lokale notabelen – zoiets sloeg Bomans niet af, vooral als er mooie jonge vrouwen aanwezig waren – werd de gevierde spreker waarschijnlijk naar het Stationsplein gebracht. Indien hij geen trein meer naar dat verre Haarlem kon halen, zal hij de nacht in het stadje hebben doorbracht. Het hotel kan Monopole zijn geweest, een immense overnachtingsgelegenheid tegenover het station. Een prachtig gebouw uit de eerste jaren van de eeuw, met een ook al enorme, houten serre.

Het werd gesloopt in 1978. Eerder in de jaren ’70 kan hotel Monopole tevens de locatie zijn geweest van Bomans’ tweede bezoek dat in de archieven wordt genoemd. De exacte datum en plek laten zich niet achterhalen. Wát we zeker weten, is dat Bomans naar Amersfoort kwam op een woensdagavond in de laatste vier weken vóór de verkiezingen voor de Tweede Kamer op 28 april 1971. De avond viel samen met een voetbalwedstrijd. Het kan 14 april zijn geweest, want op die avond kwam Ajax uit tegen Atlético Madrid. Bomans maakte toen een serie verslagen over verkiezingsbijeenkomsten; daarbij zou hij zich concentreren op de verbale vermogens van de politici. De serie zou later worden gebundeld in De Man Met De Witte Das, gecombineerd met herinneringen aan Bomans’ vader J.B. Bomans, ooit de lijsttrekker van de Roomsch-Katholieke Staatspartij.

Marcus Bakker

Over de inhoud ging hij niet, in principe dan. Want hij kon het niet laten Marcus Bakker (CPN) neer te zetten als ‘een voortreffelijk spreker’ naar wie je ‘ademloos luistert’, die echter ‘uitgaat van de veronderstelling, dat een voortdurend smalen op wat anderen voor juist houden, een eigen betoog oplevert’. ,,Hij schold op alles en iedereen, met een superbe toon, een bijtend sarcasme en een bittere haat.’’ Maar over eventuele alternatieven van de CPN liet Bakker zich niet uit. Bomans: ,,Wéét hij, dat de beledigingen die hij zich hier ten aanzien van ministers en volksvertegenwoordigers veroorlooft hem in Rusland terstond onvindbaar zouden maken?’’

Iets dergelijks constateerde hij bij een presentatie van Berend Udink van de CHU (Christelijk-Historische Unie, in 1980 opgegaan in het CDA). ,,Achter in de zaal bevonden zich enige ‘angry young men’, die hun onafhankelijkheid van geest voornamelijk toonden door met de handen in de zakken en luid schreeuwend enige vragen te stellen.’’ Tot Bomans’ verbazing bleef Udink kalm, beleefd en vriendelijk. Ook hier ergerde de auteur zich aan de selectieve verontwaardiging: alles in het kapitalistische Westen was fout en wie iets anders durft te zeggen, werd overstemd door gejoel en gefluit. ,,Fascistoïde trekken’’, vond Bomans.

In Amersfoort maakte de 40-jarige Hans van Mierlo zijn opwachting namens D66, destijds nog geschreven als D’66. Over de standpunten van deze partij liet Bomans zich niet uit. Het was toch al een rare avond, aangezien die samenviel met de genoemde voetbalwedstrijd. Het verkiezingscomité moet dat hebben geweten en kon daarom hebben gekozen voor hotel Monopole. Dat gebouw was groot, maar de zalen waren klein. Daar werd ook mee geadverteerd: ,,Aparte intieme zalen voor receptie, diner en vergaderingen.’’

Te elfder ure bedwongen losbandigheid

Bomans: ,,Rond de heer Van Mierlo, voorman van D’66, vond ik dan ook slechts 25 mensen verenigd. Om het gezellig te houden, zaten deze in een halve kring rond de lijsttrekker geschaard, zodat men het voorrecht had deze veelbesproken jongeman van zeer dichtbij te bezien. De heer Van Mierlo heeft het gezicht van een Leids student, over wie zijn ouders zich terecht ernstig zorgen hebben gemaakt, maar die dan nog net op zijn pootjes terecht is gekomen.’’ In het toen al wat getekende gelaat zag de auteur ‘een te elfder ure bedwongen losbandigheid’.

Van Mierlo maakte een sympathieke indruk, maar leek doodsbang te zijn om iets beter te weten en in grootspraak te vervallen. Alles wat hij zei, trok hij direct in twijfel. Wat de politicus volgens Bomans over het hoofd zag, was ‘dat wij naar dit zaaltje gekomen zijn in de mening dat hij het beter weet, want anders waren we wel thuisgebleven’.

Voorts viel hem een meisje op met een enorme strik, op de rug gedragen. Daarmee leek ze op een vlinder, die er even was neergestreken. Ze leek niet te luisteren en keek in plaats daarvan verzaligd om zich heen, ook toen de discussie over het verontreinigde milieu steeds pessimistischer werd. ,,Het hoogtepunt van haar verrukking viel samen met het opstaan van een jongeman in een zeer nauwsluitende pantalon, die verklaarde ons allemaal geen jaar meer te geven.’’ Daarna vertrok zij, ‘met half neergeslagen ogen, zoals iemand die bijna ontploft van blijdschap’. Het zal geen lange avond zijn geweest. Bomans maakte na afloop nog even een praatje met Van Mierlo – de laatste zei dat het vlinderachtige meisje hem geheel was ontgaan – en liep naar het station.

Doodsbedreigingen

D66 onderging in dat voorjaar een crisis, uitgerekend in Amersfoort. De landelijke leiding overwoog een samengaan met de PvdA en de PPR (Politieke Partij Radikalen, in 1991 opgegaan in GroenLinks). De dagbladen meldden in februari dat de bestuursleden van de Amersfoortse afdeling uit protest hun taken zouden neerleggen, en in maart dat ze dat ook hadden gedaan. Uiteindelijk bleef de fusie natuurlijk achterwege. Bomans gaat hier geheel aan voorbij, hij vond het meisje met de strik interessanter.

Hiermee zou hij wederom het beeld kunnen bevestigen dat in brede kringen opgang maakte: dat van een politieke onbenul. Volgens Harry Mulisch was hij dat zeker. Eind jaren zestig omarmden Mulisch en meer intellectuelen het marxisme, de revolutie in Cuba en Mao Zedong. Mulisch’ oude vriend Bomans, die daar in Bloemendaal in een villa woonde, was een ‘verrader’. In 1966 moest Bomans tijdelijk door de politie worden bewaakt, na doodsbedreigingen van De Rode Jeugd, die opriep tot vernielingen van gebouwen waarin Amerikaanse instellingen waren gevestigd. Mulisch stond daar achter en wist dat hij zich even niet met goed fatsoen in het gezelschap van Bomans kon vertonen. Als saloncommunist keek hij niet op een dictatortje meer of minder.

Vooral gedurende Bomans’ veelbesproken verblijf op Rottumerplaat – in juli 1971 – kwamen de angsten naar boven. Zou de Rode Jeugd hem alsnog om zeep helpen? Hij ‘scheet bagger’, zo noteerde literator Jeroen Brouwer instemmend In zijn boek De Spoken van Godfried Bomans (1982). Net goed! Hij was bovendien afgedaald tot tv-maker en behoorde dus tot de ‘vertegenwoordigers van het droef makend volk uit het Gooi dat verantwoordelijk is voor de stupidisering, infantilisering, kunsthaat en smaakverpesting’. Daarmee werden documentaires als Bomans In Triplo vlot bij het grof vuil gezet.

Kultuurkamer

Het vergde moed om Bomans’ standpunten te verdedigen als tijdloos en verfrissend-onmodieus. Hij hechtte simpelweg aan democratie. Iets wat in de oorlogsjaren al was gebleken, al sprak of schreef hij daar zelden of nooit over. Zijn verleden in het verzet was geen gespreksonderwerp. Maar het was er wel degelijk. Hij had zich niet aangesloten bij de Kultuurkamer, hetgeen hem een smak geld kostte. ‘Erik of het klein insectenboek’ was net verschenen en verkocht uitstekend. Maar Bomans ontving vanaf 1941 tot de bevrijding geen cent aan royalty’s.

Wel had hij extra uitgaven, aangezien hij in zijn woning aan de Zonnelaan in Haarlem onderdak bood aan joodse onderduikers, onder wie de uit Duitsland gevluchte operettedirigent Hans Lichtenstein en Jan ter Gouw, die eigenlijk Lou Bauer heette. Hij luisterde naar verboden radiozenders en gaf links en rechts informatie door. Het gezin van beeldhouwer en verzetsstrijder Mari Andriessen kon ook enige tijd bij hem schuilen. In 1987 werd aan Bomans – postuum dus – door het Israëlische Holocaustcentrum de Yad Vashem-onderscheiding toegekend als ‘Rechtvaardige onder de Volkeren’.

Vloerkleed

Voor de volledigheid: voordat Bomans naar Amicitia kwam, werden in Amersfoort enkele toneelstukken van hem opgevoerd. Op 18 januari 1948 speelden jongeren van de Sint Franciscus Xaverius-parochie ‘De Huistyran’ in het gebouw van de Katholieke Arbeiders Vereniging aan de Lieve Vrouwestraat. Hierin geeft een strenge oud-kolonel in een dronken bui alsnog zijn fiat aan het huwelijk van zijn dochter. Het Dagblad voor Amersfoort prees de mimiek van enkele spelers. En: ,,De decoratie was goed, al lag het vloerkleed wel eens in de weg.’’

Een jaar later, op 25 februari 1949, speelden leden van de Amersfoortse Gymnasiastenclub in Amicitia ‘Bloed en Liefde’. Het werd een enorm succes, zo schreef het Dagblad voor Amersfoort, ‘niet alleen door de zotheid in het stuk, maar meer nog door het geestdriftige, animerende spel’. De avond werd afgesloten ‘met bloemen en een driewerf hoera’.

Bomans schreef de treurspel-parodie Bloed en Liefde als 18-jarige gymnasiast. Talrijke personages uit de wereldgeschiedenis – Jacoba van Beieren, Iwan de Verschrikkelijke, Karel de Vijfde en vele anderen – ontmoeten elkaar, ook al leefden ze in totaal andere tijden. Ze spreken een bombastisch, archaïsch taaltje á la Victor Hugo. Geregeld komt een soldaat binnenrennen met de mededeling ‘Heer, de vijand naakt!’ Volgens Bomans’ medescholieren vertoonden de personages eigenschappen van zijn leraren. Ze gaan allemaal dood. De docenten zelf waren destijds ‘not amused’.

Had mijn vrouw maar één zo’n been

En nu we toch onder elkaar zijn: in beschouwingen over Bomans – hij is op 22 december vijftig jaar dood, dus gaan er nog veel komen, daar is geen ontkomen aan – wordt routinematig beweerd dat de auteur ooit, na een blik op de benen van Marlène Dietrich, zich had laten ontvallen: ,,Had mijn vrouw maar één zo’n been.’’ Zelfs wie destijds keek, meent zich dit zo te herinneren. Maar het is niet waar.

Hij zei bij de prijsuitreiking van het Grand Gala du Disque in 1963, terwijl Dietrich nog moest opkomen: ,,Ik zat eens in de bioscoop en daar werd een film van Marlène Dietrich vertoond. En ik genóót natuurlijk… en naast mij zat een héél oud mannetje… ook te zúchten van verrukking. Opeens stootte die man mij aan in het donker, en dat is wérkelijk gebeurd, en die zei toen vanuit de grónd van zijn hart… : ‘Had mijn vrouw maar één zo’n been’.’’ Toen pas liet hij Dietrich opkomen. Ze droeg een lange rok.