Schrijver en publicist Henk Pröpper was nog maar net verhuisd naar zijn geliefde Parijs, toen de stad tot stilstand kwam, en zijn hart bijna ook. Eenmaal voorzien van een pacemaker trok hij in het ene uurtje per dag dat het Parijzenaars was toegestaan, de stad in. Er ging een nieuwe wereld voor hem open.

Voor Henk Pröpper (62), voormalig directeur van het Nederlands Letterenfonds en uitgeverij De Bezige Bij, was een lage hartslag op zich niets om zich zorgen over te maken. Hij functioneerde al jaren op een tempo van veertig slagen per minuut, en een paar slagen minder ging ook nog wel. Als duurloper slaat zijn hart nu eenmaal trager dan gangbaar.

Maar na een stressvolle tijd en een haastige verhuizing begin vorig jaar van Amsterdam naar Parijs, lag Pröpper ineens ziek op de bank. Gebrek een zuurstof, gebrek aan energie – dit was niet goed. Hij ging onder het mes en kreeg een pacemaker.

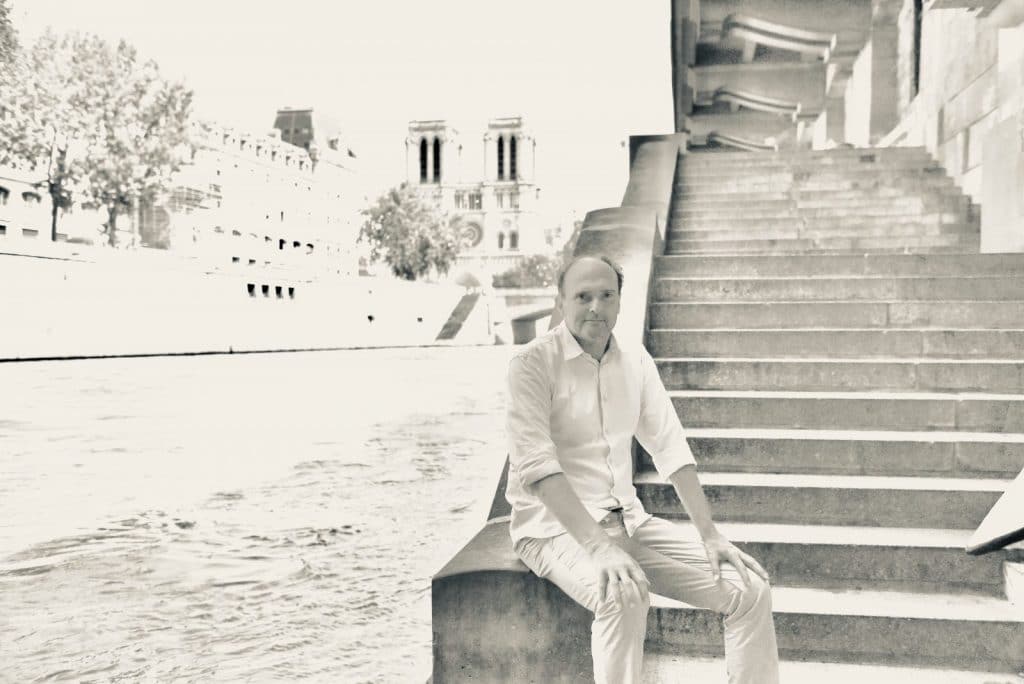

De maanden erna wandelde Pröpper voor zijn herstel door een verlaten stad, tijdens het ene uurtje per dag dat inwoners van Parijs tijdens de lockdown naar buiten mochten. Hartslag 27 is de literaire neerslag van deze bewogen periode van stilstand; een filosofisch, mijmerend boek met de prettig trage hartenklop van de schrijver, die de lezer meevoert door de stad en de Europese literatuur en geschiedenis. Onder meer naar de Tuileries, waar Pröpper op een zonovergoten dag vertelt over het afgelopen jaar.

Levenskracht

Hoe was het om uw hartslag op de monitor steeds verder te zien afnemen?

‘Het gekke was dat ik tot niets meer in staat was, terwijl mijn hersenen tegelijk heel helder bleven en dit hele proces zich zagen voltrekken. Vanwege Covid lag ik helemaal alleen op de IC, er mocht niemand op bezoek komen en ik voelde me verlaten. Omdat ik niet kon slapen, lag ik naar mijn polsslag te kijken op het scherm. Ik was verbaasd dat ik er zo rustig en helder naar kon kijken hoe mijn hartslag per uur verder weg zakte. Tot hoever kan dit gaan, vroeg ik me af. Tot een hartslag van 27 dus.

Ik dacht aan mijn vrouw Myriam en onze kinderen: als ik erin zou blijven, hoe moest het dan met hen verder? Toch had ik niet écht het gevoel dat ik zou sterven. Een belangrijk thema in het boek is de levenskracht van de mens, die de kern is van het leven. Kennelijk vertrouwde ik erop dat die er was en zou blijven.’

In de maanden erna dwaalde u door een leeg Parijs om te herstellen.

‘Dat was heel onwerkelijk. Eén uur per dag mochten we naar buiten, niet verder dan anderhalve kilometer – en later nog maar een kilometer– van huis. Omdat er geen verkeer was, kon ik een gegeven moment zelfs de mest op de landerijen ruiken, twintig tot vijfentwintig kilometer verderop.’

‘Al wandelend ontdekte ik dat de afwezigheid van leven op straat niet betekende dat er niets te zien viel, integendeel. Die leegte zorgde ervoor dat mijn aandacht voor alles wat ik zag, aanzienlijk toenam. Niet alleen voor elk levend wezen dat ik tegenkwam, maar ook voor beeldhouwwerken, gebouwen, straten. Voor hoe de stad eigenlijk is gebouwd. Normaal neem je dat eigenlijk allemaal voor vanzelfsprekend als je ergens woont.’

‘Mijn vrouw is Française en toen ik directeur was van het Institut Néerlandais, woonden we jaren in Parijs. Maar pas nu kreeg ik oog voor de plekken die je als toerist juist zou bekijken. Ik ging op zoek naar plaquettes, beelden, herdenkingsplekken voor mensen die zijn gevallen in de oorlog of een belangrijk boek hebben geschreven, en herlas de schrijvers die veel hebben betekend in mijn leven. Zo kon ik in een tijd waarin ik niemand zag toch “vrienden” ontmoeten.’

Verlichtte dat uw eenzaamheid?

‘Enorm, ja. Mijn vrouw werkt als arts in de zorg en reed overdag in haar autootje door Parijs om op huisbezoek te gaan bij haar patiënten. Ik was veel alleen, kon niemand opzoeken en probeerde uit de leegte en stilstand toch iets te ontketenen. Het wandelen leidde tot een dagelijkse stroom van bezigheden, zoals lezen en het schrijven van dit boek. Te zien hoe allerlei personen uit andere perioden van de geschiedenis, die misschien nog wel heftiger waren dan deze lockdown, een waardevol gebaar maakten naar hun medemens, gaf me steun.’

Kunst en literatuur

Elegant verbindt Pröpper in Hartslag 27 historische gebeurtenissen, kunst en literatuur en persoonlijke herinneringen met de huidige tijd. Zo herleest hij de novelle De stilte van de zee, over een vriendelijke, Frankrijk-minnende Duitse soldaat die tijdens de Tweede Wereldoorlog wordt ingekwartierd bij een zwijgzame Franse familie en tevergeefs contact probeert te maken. En wandelt hij langs de door brand verwoeste Notre-Dame naar het indrukwekkende herinneringsmonument voor de tweehonderdduizend gedeporteerde Fransen.

Ook de beelden van handen in de Tuileries, The Welcoming Hands, ruim twintig jaar geleden gemaakt door Louise Bourgeois, kregen in een tijd zonder aanrakingen ineens een andere lading. Net als de dankbrief van schrijver Albert Camus aan zijn vroegere leraar, die hij schreef toen hem in 1957 de Nobelprijs voor de Literatuur werd toegekend. Deze brief werd voorgelezen bij een herdenkingsbijeenkomst voor Samuel Paty, de leraar die vorig jaar op straat werd onthoofd.

‘Ik vond het mooi om het over die brief te hebben, omdat het iets zegt over het belang van leraren – een onderwerp waar het tijdens de lockdown vaak over ging. Het verhaal draait niet om vertoeven in de geschiedenis omdat de geschiedenis zo fantastisch is, maar nadenken over wat je er nú aan hebt en hoe je kracht aan die voorbeelden kunt ontlenen om goed te leven. Toen de brief van Camus werd voorgedragen, inspireerde die me om na te gaan welke personen belangrijk voor me zijn geweest en hoe ik dankzij hen ben geworden wie ik nu ben. Sommigen heb ik een brief geschreven. Daardoor heb ik onlangs een oude vriend voor het eerst in bijna veertig jaar gezien.’

Had u zelf ook zo’n leraar in uw leven?

‘Ja, al was hij niet letterlijk een leraar. Toen ik uit het oosten van het land als jongen van 18 in Amsterdam terechtkwam om te gaan studeren, was die stad voor mij een onwaarschijnlijk grote metropool waar ik bijna bang voor was. Elke dag nam ik dezelfde tram, lijn 17, die vanaf het Centraal Station langs mijn huis en faculteit ging. Verder durfde ik niet; ik zat alleen maar op mijn studentenkamer te lezen in bed.’

‘Tot ik op een gegeven moment een vriend kreeg, een fotograaf en student Nederlands, die al begin dertig was en me op sleeptouw nam door de stad. Met hem kocht ik mijn eerste leren jack en we gingen naar de kroeg. Door hem begon ik me langzaam thuis te voelen in een wereld die zoveel groter was dan ikzelf.’

‘Op mijn 21e kreeg ik een foto van hem cadeau die hij had gemaakt van precies zo’n stoel in de Tuileries als waar we nu op zitten, vroeg in de ochtend, de dauw er nog op. Een prachtige foto, die ik altijd heb bewaard. Maar de man zelf is, zoals wel meer vrienden, op een bepaald moment uit mijn leven verdwenen zonder dat ik precies weet waarom. Jaren geleden vond ik hem op een macabere manier terug. Ik woonde in New York en mijn moeder stuurde me een artikel uit NRC op over een onderwerp dat ik interessant vond. Op de achterkant van dat krantenbericht stond het overlijdensbericht van hem – een onvoorstelbaar toeval.’

Heeft deze periode nieuwe inzichten gebracht?

‘Zeker, de afgelopen tijd heeft me een stuk nederiger gemaakt. Mijn relatie met tijd, discipline en ambitie is veranderd. Ik moest altijd zo hard mogelijk, met alles. Mijn vader gaf mij bijvoorbeeld ooit een boekje met alle uitslagen van alle Olympische Spelen tot 1968 – die kende ik niet lang daarna allemaal uit mijn hoofd. Ook heb ik altijd keihard gewerkt. Terugkijkend zie ik dat mijn leven een aaneenschakeling is geweest van te veel en te ver. Daardoor rende ik dus letterlijk en figuurlijk ook aan veel voorbij.’

Leeft u nu met meer aandacht?

‘Ja, omdat er dan meer ruimte is voor de kleine toevalligheden en ontmoetingen in het leven. In mijn boek beschrijf ik een kleine scène die me trof. Op een dag zag ik twee vrouwen aan de overkant van de Seine lopen. Het was net lente, maar ze hadden zich gekleed alsof het al hoogzomer was; heel sierlijk en kleurrijk. Dichterbij gekomen zag ik dat het oudere dames waren, die zich mooi hadden opgemaakt. Ze keken me allebei heel diep in de ogen, en er zat een krácht in hun blik, een gulzigheid voor het leven, echt onvoorstelbaar. Die pure levensvreugde stemde me enorm vrolijk. Zulke dingen merk je alleen op als je je daarvoor openstelt. Met die aandachtigheid en beminnelijkheid wil ik graag in het leven staan en met anderen omgaan.’

Henk Pröpper, Hartslag 27, 144 p., De Bezige Bij, € 20,99

Dit verhaal werd mede mogelijk gemaakt door het Steunfonds Freelance Journalisten