Manger, de nieuwe voorstelling van Boris Charmatz en Musée de la Danse, geeft toeschouwers alle ruimte. Waar je je opstelt om te kijken of juist om te luisteren, naar wie of wat je kijkt en voor hoe lang, maak je zelf uit. De Zuiveringshal op het Westergasfabriekterrein, majesteitelijk leeg en galmend, zorgt voor een wonderlijke sfeer in deze voor Charmatz’ doen redelijk ruige choreografie.

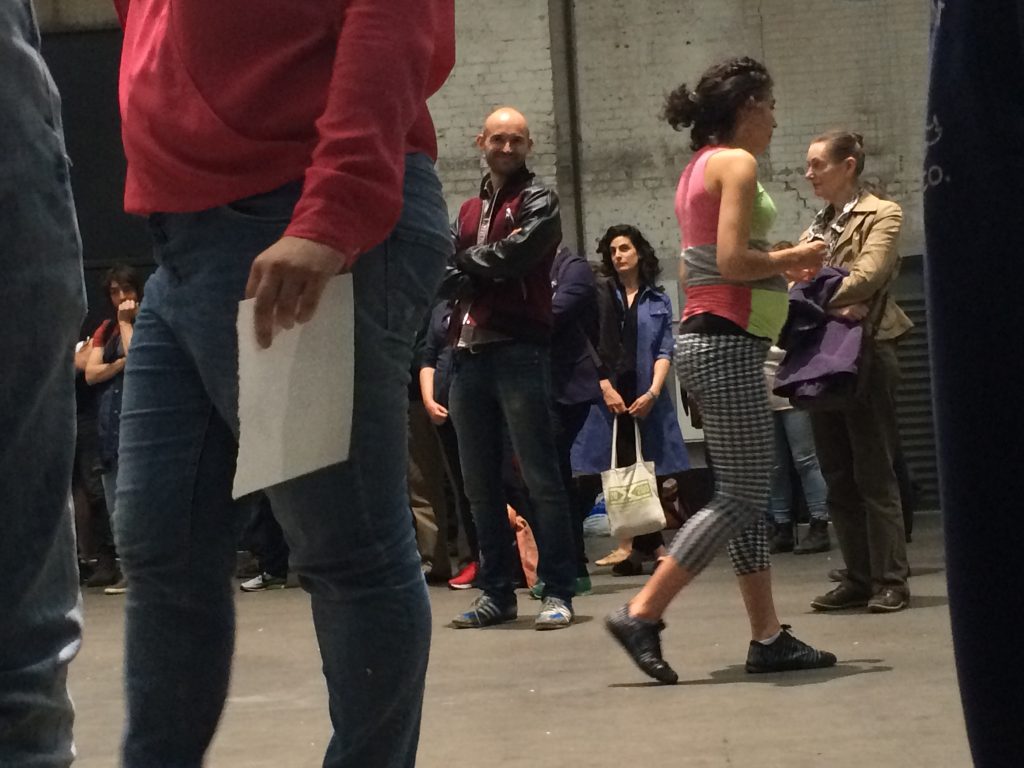

Charmatz zelf is een groot communicator (zie interview Ruhrtriënnale onderaan bij dit artikel), maar in Manger lijken de dansers aanvankelijk erg gesloten. Ook wanneer ze met elkaar interacteren, lijken ze elkaar niet te zien. Alle uitwisseling gaat via de handen, de mond en het oor. Het kijken met de ogen wordt aan het publiek overgelaten. Een publiek dat geen stoelen tot zijn beschikking heeft, maar ook geen duidelijke opstelling krijgt voorgeschreven.

Het publiek van Manger opent eigenlijk zelf de voorstelling, wanneer het de Zuiveringshal binnenzwermt. De resonantie in de hal versterkt elke achteloos genomen stap, terwijl de schoonheid van de oudbouw toeschouwers doet realiseren dat ze op een groots podium zijn beland. Toch heeft de uitwisseling tussen dansers en publiek zoals die zachtjes kauwend een aanvang neemt, ook iets heel informeels. Het is maar eten, het zijn maar wat papiertjes. Niet echt de grandeur die doorgaans met prestigieuze kunst is verbonden.

Het precieuze, heel aandachtige begin van Manger wordt daarom gevolgd door een zoektocht naar hoe te kijken, te luisteren, te zitten of te staan, een vaste plek in te nemen of je juist veel te verplaatsen. Ondertussen bewegen de dansers zich vooral over de grond en vormen zij steeds meer een aparte, vertakte constructie, dwars door de losjes verspreide mensenmassa en de immense ruimte heen. Zij voeren hun partituur uit in hun tijd, bepaald door het tempo van het zingen/eten/dansen, woekerend met hun ruimte. De structuur die zo ontstaat, zeg een choreografie voor 14 dansers en 250 andere mensen, levert prachtige uitzichten en doorkijkjes op, maar ook haast opdringerig intieme momenten.

De tast en het eten, het voelen en het doen, het zingen zonder kijken, lijkt Charmatz uitgedaagd te hebben tot een wonderbaarlijke ode aan de hooligan-monnik. Het a cappella-zingen en schreeuwen, spreken en kreunen verbindt alles en iedereen. Het levert prachtige momenten op waarin een atonaal koor zich kruipend een weg baant, of er horizontaal wordt gediscodanst op een Frans popliedje.

Herkenbare melodieën en zeker ook de teksten, waaronder het beeldschone en hilarische l’Homme de Merde van Christoff Tarkos, geven aan de handelingen en bewegingen van de dansers soms nog een referentie mee. Maar meestal is het gissen naar wat je nu eigenlijk meemaakt. Niet alleen het verteren van het papier in het binnenste van de performers wordt in Manger aan het oog onttrokken, maar ook wat er allemaal op die auwel-A-viertjes geschreven had kunnen staan – vragen naar allerlei vormen van consumptie neem ik aan.

De bewegingen van de dansers gaan semantisch ondergronds. Je kunt ze als teken van iets opvatten, maar dat doe je dan wel heel erg zelf. Het verteren, tot je nemen, innemen, verwerken en doorwerken, wordt een onderwerp op zich. Het lichaam is niet vormloos – integendeel. Maar het voorkomen gaat met zo weinig ‘stijl en gratie’ gepaard, dat het eerder herinnert aan diepe, heerlijk asociale dronkenschap of intense seksuele of culinaire uitspatting, noem het hooligan-vreugde.

Alsof Charmatz ons het lichaam opnieuw wil tonen. Een lichaam dat het ondanks alle gezondheidsmanie redelijk zwaar te verduren heeft, qua stress als collateral damage van nastrevenswaardige, uiterlijke en innerlijke idealen. Of de lichamen van al die mensen die er alleen voor staan en het niet meer opbrengen zich in vol vertrouwen tot hun medemensen te richten, mensen die down en out zijn, zwervend. Maar ook een lichaam dat zich ongeneerd te buiten gaat en zich schaamteloos laat bekijken.

De galm in de hal, de steeds opnieuw aanzwellende a cappella zang, het gekozen repertoire en het immer gezamenlijk optrekken van de dansers maakt van Manger ook een soort congregatie, religieus of anderszinds. Niemand zei boete of spijt, maar het lijkt het vanzelfsprekende rustpunt temidden van alle lichamelijke euforie en ellende.

Manger genereert een wonderlijke combinatie van theaterkijken, museumwandel en kloostergang. Juist door het weglaten van allerlei gangbare theater- en danszaken, zoals de vaste tribune, de centrale blik en een lekker gestileerd voorkomen, geeft de voorstelling de toeschouwer alle ruimte, zoals je dat in galerieën, musea of openluchtopstellingen tegenkomt. Tijdens een zoveelste zangpartij bekroop mij echter ook een iets te roomse herinnering. Ik had behoefte aan een man met een hondje, een brommer of een vogel in de lucht, of kinderen die zich al spelend nergens iets van aantrekken, als die man, het hondje en de vogel. Niet dat ik mee wilde dansen, zoals sommige andere bezoekers na afloop zeiden. Maar het ritueel werd mij te dwingend. Als toerist in andermans kerk, waar je niet zomaar kunt opstaan en weggaan een beledigimg zou zijn. – En toch, vanavond lekker nog een keertje kijken.

Manger is nog te zien op 5 en 6 juni in De Zuiveringshal, Westergasfabriekterrein, Amsterdam. Aanvang 20:30. Voor meer informtie zie ijdens het Holland Festival.

Charmatz geinterviewd voorafgaand aan de premiere van Manger tijdens de RuhrTriennale 2014 in Bochum.