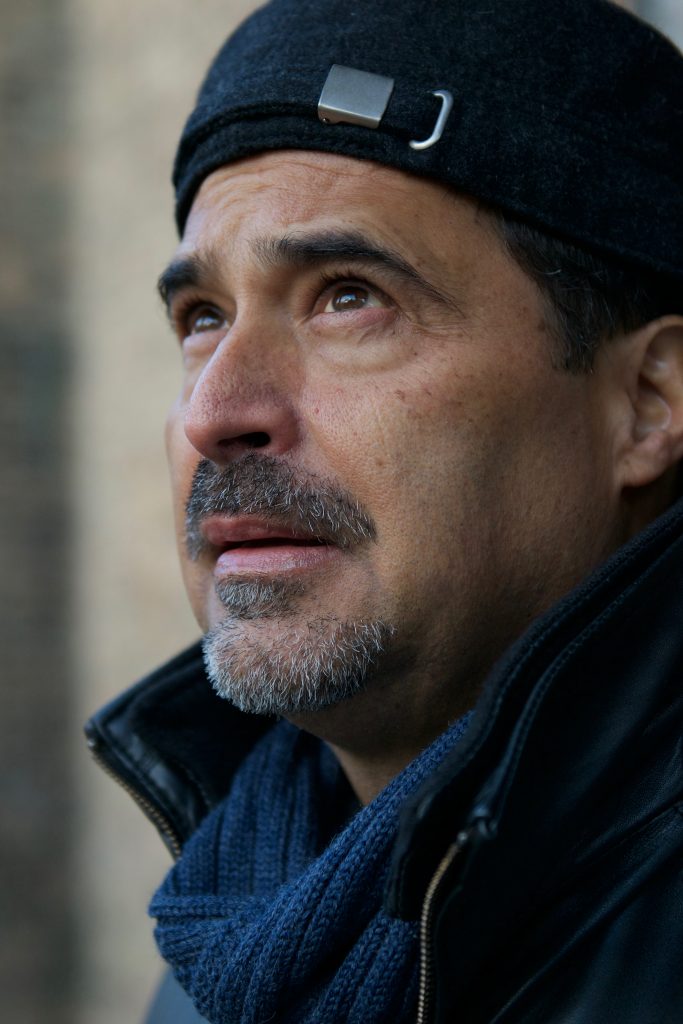

Het schrijven kostte hem zijn huwelijk, hij wordt geschaduwd door de geheime dienst en loopt de kans in Angola te worden opgepakt. Maar José Eduardo Agualusa, die met zijn nieuwe roman Een algemene theorie van het vergeten kans maakt op de Man Booker International Prize 2016, peinst er niet over de pen erbij neer te leggen. ‘Ik laat me niet tot zwijgen brengen.’

Onlangs liep José Eduardo Agualusa (1960) op straat in zijn woonplaats Lissabon, toen hij de agent van de Angolese geheime dienst voor de deur aantrof, zijn ‘eigen agent’, die hem al zo lang volgt dat hij de man bij naam kent. ‘Wat doe jij hier nou?’ vroeg hij aan de agent. Die wees naar het gebouw naast dat waar Agualusa in woont. ‘Dat gebouw daar… We hebben het gekocht.’ ‘Maar waarom?’ vroeg de schrijver verbaasd. De agent keek hem aan en zei: ‘Ach, kom op, dat weet je best…’

José Eduardo Agualusa barst in lachen uit, en schudt verbaasd en ongelovig zijn hoofd. De Angolese geheime dienst die een huis in Portugal koopt om hém in de gaten te houden. ‘Misschien is het niet waar en zei hij het alleen om mij angst aan te jagen. Maar het kan net zo goed wel waar zijn; ze hebben het geld ervoor. Ze denken in elk geval dat ik veel belangrijker ben dan het geval is.’

Schrijver José Eduardo Agualusa, geboren in Huambo in Angola maar woonachtig in Portugal en Brazilië, is bescheiden. De auteur van bijzondere romans als Een steen onder water (2003), De handelaar in verledens (2007), De vrouwen van mijn vader (2009) en Het labyrinth van Luanda (2010) geldt namelijk wel degelijk als een van de belangrijkste Portugeestalige schrijvers. Zijn meest recente roman Een algemene theorie van het vergeten werd bekroond met de Premio Fernando Namora, en staat bovendien op de shortlist voor de prestigieuze Man Booker International Prize van dit jaar, zo werd vandaag bekendgemaakt.

Agualusa’s magisch-realistische romans draaien om thema’s als fictie en werkelijkheid, leugens versus waarheid, en zijn nadrukkelijk geworteld in de geschiedenis en het heden van zijn vaderland Angola. Onafhankelijkheid, burgeroorlog en dictatuur spelen in elke roman een belangrijke rol, en Agualusa laat zich kritisch uit over verschijnselen die daarmee samenhangen, zoals racisme, armoede, wreedheid en geweld. Zo ook in het prachtige Een algemene theorie van het vergeten, een wreed en tegelijk teder verhaal over de vrouw Ludo die zich aan de vooravond van de Angolese onafhankelijkheid inmetselt in haar woning en vervolgens dertig jaar geschiedenis aan zich voorbij ziet glijden.

Zwijgen

Agualusa is al bijna een jaar niet meer in Angola geweest, vanwege het risico te worden opgepakt. ‘Het is gevaarlijk om een mening te hebben. Mijn boeken worden niet verboden. Het zijn niet de boeken die als probleem worden gezien, maar vooral het feit dat je als schrijver daarmee ook de gelegenheid hebt om artikelen te publiceren en interviews te geven.’

De lange armen van de man die dezelfde voornamen draagt als hij, president José Eduardo dos Santos, reiken tot in Portugal, en dan niet alleen tot aan Agualusa’s eigen voordeur, vertelt hij. De Angolese regering heeft een aantal belangrijke bedrijven en kranten in Portugal opgekocht, en heeft zelfs geprobeerd de nationale publieke televisiezender in handen te krijgen, maar dat is mislukt. ‘Ze verspreiden geen propaganda, het is eerder dat bepaalde gebeurtenissen gewoon niet worden gemeld. Ze zwijgen zaken dood. Een vriend van me, rapper Luaty Beirão, werd vorig jaar opgepakt, samen met veertien anderen, omdat hij een moord op de president en een staatsgreep zou hebben beraamd. In werkelijkheid hielden ze alleen vredelievende demonstraties en lazen ze een boek van politicoloog Gene Sharp. Een van de belangrijkste onafhankelijke kranten in Portugal plaatste er stukken over en publiceerde zelfs een interview met Luaty, terwijl veel andere kranten erover zwegen.’

Monsters

In een land als Nederland, zegt Agualusa, zijn er genoeg onafhankelijke media, maar omdat dat niet het geval is in een land als Angola, heeft literatuur een groot maatschappelijk belang. ‘Een boek is een plek van debat en vrijheid van denken, waar geen concessies worden gedaan aan mensenrechten. Ik geloof erin dat literatuur een bijdrage levert aan debat en onafhankelijkheid. Ik hoop dat mijn boeken daar een voorbeeld van zijn. Dat geeft schrijvers een grote verantwoordelijkheid. Natuurlijk denk je daar niet aan terwijl je schrijft, anders zou ik niet kunnen schrijven – ik werk vanuit passie. Maar ik stel wel vragen waarvan ik denk dat die belangrijk zijn om te stellen in Angola.

Ik schrijf veel over het kwaad, omdat dat zo moeilijk te begrijpen valt. In een land als Angola word je omgeven door mensen die in normale omstandigheden normale personen zouden zijn. Maar een dictatuur verandert normale mensen in monsters. En sommige in helden. Luaty bijvoorbeeld is een ongelooflijke man. Als ik van hem een personage zou maken, zou je denken dat ik overdreef. Luaty’s vader was de beste vriend van de president, en de directeur van de Eduardo dos Santos Foundation. Volgens vrienden die in die tijd in de gevangenis zaten, was hij een brute folteraar. Luaty is dus opgegroeid in de hoge regionen van het systeem, maar heeft zich daar altijd tegen verzet. Na zijn studie in Europa besloot Luaty terug te keren naar Angola, en deed dat te voet – men verklaarde hem voor gek en iedereen zei dat het hem nooit zou lukken. Maar het lukte hem wel.

Luaty spreekt zich al jaren uit tegen het regime. Tijdens een grote show waar hij in optrad, riep hij tegen de zoon van de president die daar ook aanwezig was, dat het na 33 jaar afgelopen was met de heerschappij van zijn vader. Het hele publiek scandeerde met hem mee. De regering en de president waren in alle staten.

Hij is al talloze keren gearresteerd, ze hebben hem van alles aangedaan, en toch ging hij elke keer weer de straat op, tot hij vorig jaar samen met die groep van veertien anderen opnieuw werd gearresteerd. Toen hij na zes maanden nog vastzat zonder proces, ging hij in hongerstaking. Na 36 dagen – hij ging er bijna aan onderdoor – kwam eindelijk het proces. Nu wachten ze onder huisarrest het vonnis af.’

Alleen

Luaty is een échte held, wil Agualusa er maar mee zeggen, maar toch lijkt zijn eigen situatie wel een beetje op die van zijn vriend. Zijn voormalige echtgenote kwam uit een rijke familie in Luanda, die banden had met de macht. ‘Steeds vroegen mijn vrouw en familieleden waarom ik toch over zulke onderwerpen schreef, of ik daar niet mee kon stoppen. Dat is toch niet nodig, zeiden ze tegen me, hou ermee op. Ze keurden het af. De regering heeft me zelfs geld geboden, om tien jaar in Amerika te gaan studeren. Ik zei mijn vrouw: we hebben twee kinderen. Hoe zou ik ze later moeten uitleggen dat ik heb gezwegen in een tijd waarin mensen werden omgebracht of in de gevangenis verdwenen? Ik kan niet zwijgen. Ik laat me niet het zwijgen opleggen. En áls je je mond opendoet in een situatie als deze, kun je er gewoonweg ook niet meer mee stoppen. Ik kan niet ophouden met praten – zó woedend ben ik. Het is als een soort koorts.’

Het kostte hem uiteindelijk zijn huwelijk. Moed en waardering gaan niet per se hand in hand. ‘Het is niet zoals in films. Uiteindelijk sta je alleen. Je familie en allerlei andere mensen om je heen zijn het niet eens met wat je doet. Maar ik doe wat ik wil doen, en dat is schrijven. En daarvoor moet je vrij zijn.’

Niet alleen literatuur, met name ook internet is een middel om mensen te bevrijden uit de klauwen van dictators, weet Agualusa. ‘Toen Luaty en zijn groep waren opgepakt, vloog een minister naar Portugal om met mij in debat te gaan over dat boek van Gene Sharp. “Is het een subversief boek?” vroeg hij mij. “Ja,” zei ik, “maar alleen in een dictatuur. In een democratie zijn dergelijke boeken niet subversief.” De volgende dag werd op de publieke televisiezender in Angola een stukje van dit debat uitgezonden: het stukje waarin ik zeg dat het een subversief boek is. De rest was eruit geknipt. Maar de volgende dag al stond op Facebook het hele interview: kijk, Agualusa zei iets heel anders! Daarom zijn dictators zo bang voor internet. Dat kunnen ze niet controleren.’

Een algemene theorie van het vergeten is vertaald door Harrie Lemmens en verschenen bij uitgeverij Koppernik.

De shortlist voor de Man Booker Prize wordt bekendgemaakt op 14 april.

De stad lag achter hen. Een hoge scheidsmuur liep dwars over een open veld. Helemaal achteraan een paar boababs en daarachter een vlekkeloze blauwe horizon. Ze stapten uit. Monte maakte de twee huurlingen los en rechtte zijn rug: ‘Kapitein Jeremias, ook wel de Beul genoemd. U wordt beschuldigd van een eindeloze reeks gruweldaden. U hebt tientallen Angolese nationalisten gemarteld en vermoord. Een paar van onze kameraden zouden u graag voor de rechter zien. Ik vind dat we geen tijd moeten verknoeien aan processen. Het volk heeft u al veroordeeld.’

(…)

Monte liep terug naar de auto. De soldaten duwden de Portugezen naar de muur en verwijderden zich een paar meter. Een van hen trok een pistool uit zijn riem, richtte dat met een verstrooid, bijna verveeld gebaar en schoot drie keer. Jeremias de Beul viel op zijn rug. Hoog in de lucht zag hij vogels vliegen. Op de muur vol bloedvlekken en kogelgaten las hij, geschreven met rode verf, niet a luta maar o luto continua, niet de strijd gaat door, maar de rouw.