‘Ik heb er 18 jaar over gedaan om een nieuwe opname te maken’, zegt de Kroatische pianist Ivo Pogorelich (1958) met een bescheiden glimlach. ‘Net zoveel tijd als een baby nodig heeft om meerderjarig te worden.’ Het is woensdag 2 november. Een bijzonder moment, want die dag gaat Pogorelichs cd-loze nieuwe opname van Beethovens Pianosonate’s nr. 22 en nr. 24 via het Online-Klassik-Musikportal Idagio het web op. Idagio is in 2015 opgezet door Till Janzczukowicz om ‘New and exclusive recordings by the world’s greatest musicians’ op eigentijdse wijze te verspreiden in de vorm van streaming. Veronderstelling is dat er zich onder de naar schatting 5 miljard Smartphone-bezitters meer luisterpotentieel bevind, dan bij het gestaag krimpende publiek dat op de ouderwetse manier van klassieke muziek geniet.

Digitale koploper

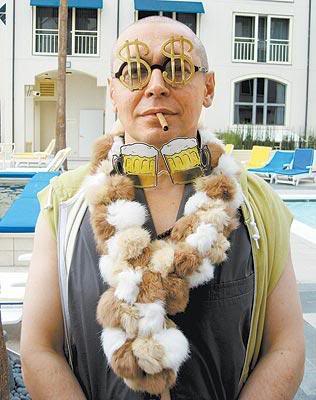

Pogorelich, die ik die dag even spreek voor zijn concert in Muziekgebouw Eindhoven, is er trots op een koploper met streaming te zijn. Zelf heeft hij helemaal niets met de digitale wereld van smartphones en laptops. Hij heeft een wollen mutsje op het kaalgeschoren hoofd, bergschoenen aan, een folkloristische sjaal om zijn nek, een dik gebreid vest en een oranje rugzakje om. Hij ziet er tijdens zijn ochtendrepetitie in de grote zaal uit als een backpacker, die wil gaan jammen op de beide Steinways, waarvan hij er eentje moet kiezen voor het avondconcert. Hij is lyrisch over de schitterende opnametechniek van zijn geavanceerde Beethoven- opname: ‘Vergelijk het met foto’s met een hoge resolutie. Je hoort en ziet alles oneindig veel scherper, de kleuren zijn extra helder en genuanceerd.’

Volgens Pogorelich is het de hoogste tijd om nieuwe publieksgroepen aan te boren: ‘Om de de jongere generaties te bereiken, moeten we de kunst verspreiden via de platforms die zij gebruiken. Idagio biedt mij als musicus de kans om mijn opnames wereldwijd verkrijgbaar te maken in een fractie van een seconde. Ik vind het alarmerend dat jongeren voortdurend naar hun smartphones staren en spreken door middel van headsets. Maar ze zijn ook druk bezig met het ontwikkelen van instincten om in die virtuele wereld hun intuïtie te kunnen volgen. Ze zijn een onpartijdig en aandachtig publiek. Ze vormen een groot potentieel voor de klassieke muziek. Bovendien maakt Idagio gebruik van de meest geavanceerde opnametechnieken, wat de levensvatbaarheid van de muziek ten goede komt.’

Klankschoonheid

Pogorelichs enthousiasme blijkt terecht, want de klankkwaliteit van zijn streaming–debuut blijkt bij beluistering kristalhelder en komt zo direct en natuurlijk over, dat het wel lijkt alsof de pianist in je eigen huiskamer Beethoven zit te spelen. Nog belangrijker is de verrassende muzikale kwaliteit van dit nieuwe Beethoven & Pogorelich-document. Alle bezwaren tegen de extreme interpretaties van Pogorelich verdwijnen als sneeuw voor de zon in de transparant resonerende stralenpracht van deze nieuwe ‘opname’. Dat is mooi, want na de dood van zijn vrouw en lerares Aliza Kezeradze in 1996 ging het bergaf. Hij zweeg een aantal jaren, ging sieraden ontwerpen, leerde Spaans, schreef gedichten en ging bij zijn terugkeer op de concertpodia zo excentriek spelen dat hij zijn publiek en de critici doorgaans tot wanhoop drijft.

Pogorelich klinkt op Idagio nog altijd eigenzinnig en soms tegendraads, maar zijn fascinerende Beethoven klinkt desondanks uitgebalanceerd en coherent. De tempi en rubati zijn geloofwaardig, de dynamiek is contrastrijk zonder in fortes pijn te doen aan je oren. De muzikale lijnen stromen door in plaats van te stagneren en de klankschoonheid is op veel momenten buitengewoon. Alsof Idagio erin geslaagd is de getergde pianist het vertrouwen te schenken en de veiligheid te bieden om in de studio optimaal te kunnen experimenteren met zijn ‘deconstructies’, zonder al bij voorbaat geblokkeerd te raken door de vernietigende kritiek waaraan hij de laatste jaren bloot staat.

Kop eraf

Het zal je maar gebeuren. Eerst wordt je wereldwijd tot pianoheld verklaard, dan raak je door ziekte en persoonlijke problemen na zestien jaar succes op een zijspoor, daarna vat je de moed op om toch weer concerten te gaan geven en vervolgens sabelt iedereen met genadeloos genoegen je kop eraf. De komeet van Pogorelich schoot omhoog, toen hij het Chopin Concours in 1980 niet won. Een opgewonden Martha Argerich, Nikita Magaloff en andere opstandige juryleden stapten op omdat zo’n geniaal pianotalent als Pogorelich tenminste in de finale had moeten komen.

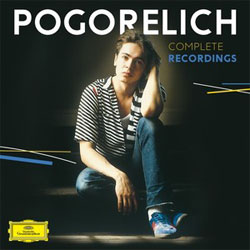

Vladimir Horowitz verklaarde nadat hij Pogorelich had horen spelen: ‘Nu kan ik eindelijk rustig dood gaan.’ Deutsche Grammophon rook meteen geld en dook er sensatiebelust bovenop. Het label lanceerde hem als het tegendraadse ‘pop-idool’ onder de klassieke meesterpianisten. Dat was slim, want met de veertien cd’s van de destijds beeldschone en revolutionair goed spelende Pogorelich doet Deutsche Grammophon nu nog altijd goede zaken.

Integer en authentiek

Pogorelich, geboren in Belgrado als zoon van een Kroatische contrabassist en een Servische moeder, bleek tijdens zijn gouden jaren allesbehalve een egocentrische user. Met het vele geld dat hij verdiende ondersteunde hij een ziekenhuis voor moeders en kinderen in Sarajevo. Hij hielp het Rode Kruis bij de wederopbouw van kapotgeschoten gebouwen en richtte een idealistisch concours voor volwassen pianisten op in Pasadena. Met zijn Pogorelich Festival in Bad Wörishofen hielp hij jonge musici op weg in zijn en hij ondersteunde de strijd tegen ziektes als kanker en multiple sclerosis.

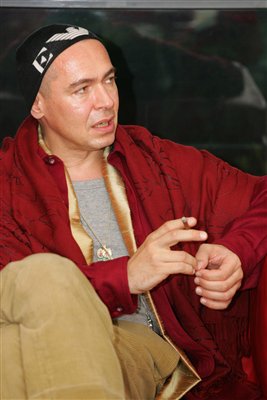

In 1988 werd hij benoemd tot Goodwill Ambassador van UNESCO. Dat Pogorelich van nature een zachtmoedige en sociale inborst heeft, is duidelijk. Maar de pijn van het vele leed dat hem is overkomen, wordt al snel zichtbaar in zijn schuwe oogopslag. Zijn manier van praten is vriendelijk en heel intelligent, maar getuigt ook van een buitengewone kwetsbaarheid, die verergerd lijkt te zijn door de eenzaamheid en het onbegrip waardoor hij al jaren wordt omringd. Immers, de eens zo heilig verklaarde Pogorelich wordt nu afgeschilderd als de onevenwichtige dorpsgek onder de grote pianisten.

Geperverteerd

Zijn muzikale zoektocht wordt niet begrepen, zijn intenties worden niet gehoord, zijn integere bedoelingen worden al bij voorbaat en masse geperverteerd. Had-ie destijds maar niet zo beroemd moeten worden, had-ie maar niet zo ijdel en zo arrogant moeten zijn… Dat is dubbel kwetsend voor Pogorelich, omdat hij deep down nooit uit is geweest op zijn flamboyante sterrenstatus. Hij heeft er hooguit een beetje mee gekoketteerd.

Telkens weer heeft hij al vanaf 1980 in interviews benadrukt, dat musiceren voor hem ‘heel hard werken’ is, dat ‘alles afhangt van goede leermeesters’ en dat het hem te doen is om ‘het ontdekken van de schatten die verborgen liggen in de partituur’, die als een ‘dood boek’ in de kast staat totdat een musicus alle noten die erin staan weer tot leven wekt.

Mooispeler

Mooispeler

In die levenslange zoektocht naar waarheid en echtheid is Pogorelich volstrekt integer en authentiek. Hij wil niet choqueren, maar structuren blootleggen. Hij wil de schoonheid die in de muziek verborgen ligt op meer eigentijdse manieren laten horen. Net als Pollini en Michelangeli is Pogorelich nooit een ‘mooispeler’ geweest. Hij behoort tot de ‘nieuwe zakelijken’ onder de pianisten. Hij wil breken met de tradities om klassieke muziek een herkansing te geven in een nieuw tijdperk. Hij is een constructivist, een modernist in een wereld waarin de klassieke muziek gevangen raakte in een elitaire wereld van pluche, van fluwelen normen en waarden, die de muziek vroeg of laat dreigen te verstikken.

En toegegeven, in het bestrijden van die traditie slaat hij de laatste jaren soms behoorlijk door. Maar als je er als luisteraar in slaagt je verwachtingspatroon op non-actief te stellen, voert Pogorelich je bij momenten mee naar een fascinerende wereld vol boeiende constructies, bijtende kleuren en extreme klanken. Vergelijk het met de schilderkunst, dan hoor je dat Pogorelich als een Picasso – die heus net zo mooi kon schilderen als Rubens of Renoir- de muziek als het ware uit elkaar trekt, juist om de muziek een nieuw gezicht te geven. Of het nu om Beethoven of Rachmaninoff gaat.

Talentvolle chaos

Hoe nu klonk de omstreden maestro op de dag dat zijn ontwapenende en ontroerende Beethoven-opname op Idagio uitkwam live in Muziekgebouw Eindhoven, waar hij zich uitleefde in Chopin, Schumann, Mozart en Rachmaninoff? Bijna als een slaapwandelaar begaf Pogorelich zich in jacquet naar de uitverkoren vleugel, zette de verfomfaaide bladmuziek van Chopin op de standaard van de vleugel, gebaarde de blaadjesomslaanster direct naast hem te gaan zitten en wiep de overige partituren voor haar voeten op de grond.

Chopins Ballade nr. 2 in F, op. 38 werd ingezet met een delicate lyriek, die al snel werd gecontrasteerd met het oorverdovend tumult van ongenaakbaar hamerende bassen (vraag: is het toeval dat Pogorelichs vader contrabassist was?) in fortissimo passages. Het leek alsof elke harmonische wending ontleed en aangeduid diende te worden in zijn kale essentie, wat weer ten koste ging van de samenhang, de vloeiende beweging en soms prachtige zingende melodielijnen.

Getraumatiseerd

Het geheel kwam over als een chaos, waaruit mooie momenten steeds weer even oplichtten als waterdruppels die in het zonlicht reflecteren. Ook tijdens Chopins Scherzo nr. 3 in cis op. 39 en Schumanns Faschingsschwanck aus Wien op. 26 was er vooral sprake van een bijna ondraaglijke spanning tussen Pogorelich’ buitengewone talent voor pianospelen en zijn bij vlagen bizarre ‘gebrek’ aan overzicht en samenhang. Parelende lyriek werd afgestraft door beukende dramatiek, romantische melodielijnen gingen ten onder in duistere moerassen vol angstaanjagende structuren en onheilspellende klanken, hemels gezang raakte verstoord door demonische verbrokkeling, alsof het een permanente strijd tussen goed en kwaad betrof.

Dat alles werd beter tijdens de Fantasie in c, KV 475 van Mozart, die net als Pogorelich veel meer verstand had van hemel en hel dan de gemiddelde wereldburger. Het was alsof de diepzinnige en spirituele noten van Mozart de getraumatiseerde pianist kalmeerden. Ze voerden hem mee naar metafysische vergezichten, waarbij als vanzelf zijn innerlijke spanningen werden verzacht. Ook de muzikale match tussen Pogorelich en Rachmaninoff was van nature vruchtbaar en enigszins geruststellend, zodat de onstuimige vertolking van diens Sonate nr. 2 in bes op. 36 nog wel de nodige ruimdenkendheid van het publiek vergde. Af en toe leek Pogorelich met zijn enorme, gerustellend bekwame pianohanden bijna een soort free jazz met Rachmaninoffs noten te bedrijven- maar al met al ook best te genieten was.

In het gareel

Mechanisch buigend, de bladmuziek op zijn rug, bedankte Pogorelich zijn publiek en gaf een toegift, helaas uit de romantische hoek. Had hij Scarlatti, Bach of Haydn gespeeld, dan zou hij zijn hele eigenaardige solorecital nog met één zwaai van zijn pianistische toverstok tot een memorabel hoogtepunt hebben kunnen omturnen. Want een ding is zeker: Pogorelich kan nog altijd fantastisch pianospelen, zolang de heldere structuur van de muziek zelf of een wijze muzikale gids hem formeel maar in het gareel houdt. Zijn wonderschone Beethoven op Idagio is een aanrader en dat geeft hoop voor de toekomst.