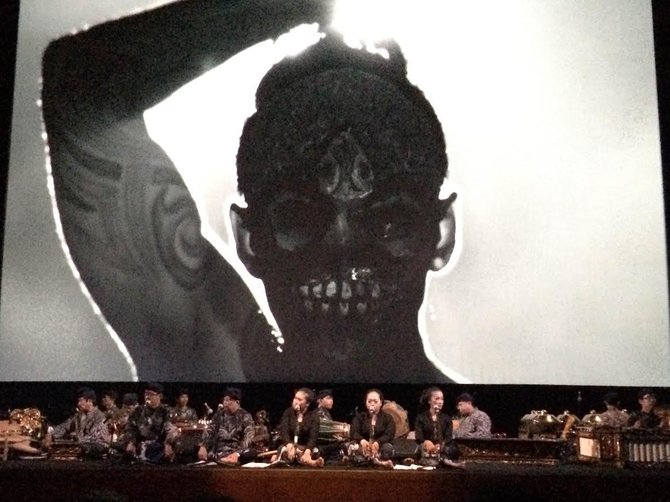

Setan Jawa is de nieuwste film van de vooraanstaande Indonesische regisseur Garin Nugroho (1961). Het is een ‘stomme’ film, geschoten in zwart-wit door Teoh Gay Hian. Hij was vorig weekend tijdens het Holland Festival te zien in het Muziekgebouw aan t IJ. De muziek bij de film wordt live gespeeld door Rahayu Supanggah Gamelan Orchestra en het Nederlands Kamerorkest. Geïnspireerd door het filmische universum van vóór de talkies, vertelt de film het verhaal van een jonge rietmatter. Hij wordt verliefd op een onbereikbaar meisje en sluit een pact met de duivel om haar alsnog te krijgen.

Surrealisme

Setan Jawa is een surrealistisch film over maatschappelijk onrecht en verlangen. Nugroho gebruikt de parallelschakeling van sociale werkelijkheid en magische en mystieke relaties, zoals dat in de Javaanse cultuur gebruikelijk is, om intrigerende verbanden te leggen en indirect sociale kritiek te leveren. Overigens ontging mij een groot deel daarvan tijdens de vertoning. Pas toen ik na afloop door beter geïnformeerde collega’s [ref]Met dank aan Ingrid Jejina, Gerard Mosterd en San Fu Maltha.[/ref] werd bijgepraat, begon de boel op zijn plaats te vallen.

Maar ook zonder kennis van Javaanse tradities of affiniteit met de complexe politiek-maatschappelijke werkelijkheid van het huidige Indonesië valt er nog een boel te zien in Setan Jawa. De film is in zes dagen opgenomen zonder gedetailleerd scenario en uit de losse hand, improviserend met de acteurs en de dansers. Het resultaat is oogverblindend mooi. Vooral de eenvoud waarmee de scènes zijn vormgegeven, als met enkele pennenstreken, valt op. Deze soberheid staat in schril contrast met de wonderbaarlijke, magisch-realistische setting waarin het verhaal zich afspeelt.

Gamelan en klassiek orkest

Gamelan-orkestleider Rahayu Supanggah en de Australische componist Iain Grandage zijn samen verantwoordelijk voor de muziek. De melodramatische lyriek voor klassieke bezetting van Grandage past bij stomme-filmhoogtepunten als Nosferatu en Metropolis. Dit verbindt zich heel vanzelfsprekend met het grillige, soms gortdroge, staccato en de prachtige toonzetting van de gamelan-traditie. Het twintigkoppig gamelan-orkest met een groot aantal zangers en zangeressen maakte sowieso grote indruk. Het expressionisme van beide muziektradities sluit wonderwel aan en is heel effectief naast en over elkaar heen gelegd.

Verbasteren

Eigenlijk lijkt het hele project Setan Jawa op een vrolijke oefening in het verbasteren en herschrijven van tradities. In de ruimte die ontstaat tussen op drift rakende verwachtingen en moeilijk plaatsbare inlossingen, kunnen ook complexe en (politiek) gevoelige zaken worden aangeraakt.

Soms zijn het relatief onschuldige aspecten die worden verhaspeld en herschikt. Het combineren van traditionele sarong-patronen met hedendaagse Indonesische fashion is daarvan een voorbeeld. De grappenmakers of plaaggeesten met hun witgeschilderde gezichten en roodgeverfde lippen leken door een Japans geisha-badje gehaald. Gevoeliger, dat kon zelfs ik snappen, liggen de erotisch geladen scènes.

18- 19 june : Holland fest , setan jawa, with live kamareorkestra amsterdam-rahayu supanggah gamelan orkestra pic.twitter.com/bWsfBG37kM

— Garin Nugroho (@garinfilm) June 5, 2017

Penis

Een tempel, waar zo nu en dan een uit steen gehouwen figuur met penis voorbij komt, speelt een prominente rol in de film. Het blijkt een hele oude hindoetempel te zijn, de Candi Sukuh, waar niet alleen seksueel plezier en vruchtbaarheid, maar ook spirituele eenwording worden gehuldigd. De vrijzinnige omgang met seksualiteit binnen het hindoeïsme is een probleem, sinds Islam in de 16e eeuw naar Java kwam. Aangewakkerd door het oprukkende moslimfundamentalisme worden ook vandaag nog tempels verwaarloosd of zelfs actief verwoest, zo vertelde een collega. Ik dacht een cultuurhistorisch hoogtepunt te zien, dat als decor mocht dienen in een mythische vertelling. In het huidige Indonesië blijkt de tempel onderdeel te zijn van een politieke machtsstrijd.

Behalve mystieke tradities en rituelen speelt ook de koloniale geschiedenis een rol in de film. Meer precies gaat het om de jaren twintig van de vorige eeuw. Toen industrialiseerde het Nederlandse koloniale bewind de landbouw. Dat zorgde voor grote armoede onder de plattelandsbevolking op Java.

Klein vergrijp

De film opent met de geschiedenis van een jongetje dat voor een klein vergrijp wordt vastgezet, compleet met ketting en ijzeren bal aan zijn voet. Het kind put enige troost uit het gezelschap van een schildpad met een prachtige snuit. Wanneer een bewaker hem tergt door met de schildpad aan de haal te gaan, vergrijpt het jongetje zich aan de bewaker. Het kind wordt daarop door andere bewakers gefolterd en de setan (satan) is geboren.

Hedendaags statement

Nugroho lijkt met deze sociale bronning van de duivelsfiguur een hedendaagse politieke statement te maken. De gruwelijke onrechtvaardigheid van het koloniale gezag kan natuurlijk doorgetrokken worden naar allerlei hedendaagse dictatoriale of corrupte regimes. Die produceren net zo goed duivels, met alle gevolgen van dien.

Dat in het huis van het aristocratische meisje geen vader leeft, is ook bijzonder. In de hele film komt eigenlijk geen vaderfiguur voor. Het voelt toch als een soort ontmanning van de film. Naast de rietmatter als pretendent komt alleen de duivel nog als relevant mannelijk wezen in beeld. Voorwaar geen klein statement, de volwassen-mannenorde tot een getergde duivelse bende te bombarderen.

Prachtige vrijscène

Allegorie

Zonder dialogen en voice-overs, met een enkele tussentitel als leidraad, moet je het als toeschouwer sowieso hebben van een gevoelige blik. Duivels en geesten, met die typische fijngesneden, kleine Javaanse maskers op, en de gareng, clowneske figuren met wit geschilderde gezichten en parmantige roodgeschilderde lippen, begeleiden de jongeman en de jongedame op hun werdegang. Setan Jawa gebruikt de specifieke historische context van het Indonesië van de jaren twintig slechts als achtergrond. De film is eerder een allegorische vertelling over hoe het slecht afloopt met een man die een pact met de duivel sluit.

De film is ingetogen en dat maakt dat de bonte stoet figuren en scènes een vanzelfsprekende kracht krijgt. Ook al begreep ik vaak niet wat er precies aan de hand was, de film dringt mij in geen geval een semi-antropologisch of anderszins exotisch perspectief op. Integendeel: Setan Jawa heeft eerder iets hips.

Kunstgrepen

In een listige combinatie van oorspronkelijkheid en artifice,[ref]kunstgrepen[/ref] van Javaanse eigenheid en artistieke toe-eigening, van een wilde vertelling geschoten in een onderkoelde stijl, met kraakhelder geënscèneerde scènes, weet Nugroho zijn publiek niet alleen te binden. Hij verleidt het ook te kijken naar een bediende die de binnenkant van de benen van haar mevrouw wast. Of maakt van de setan met het gruwelijke masker niet alleen een getergde figuur, maar ook een herkenbaar wezen van vlees en bloed.

Toe-eigening wordt wel vaker gebruikt om onderdrukking te bevechten, denk aan Geuzennamen of de homo’s die zich het sexappeal van Marilyn Monroe toe-eigenden. De niveau waarop Nugroho dit doet, in samenwerking met al die artistieke collega’s, is ongekend geraffineerd. Het lukt hem om dwars door de wirwar van tradities in film, muziek, dans, literatuur, seksuele en andere sociale gebruiken en politieke werkelijkheden een heel reëel verlangen gestalte te geven.

Gezien: Muziekgebouw aan t IJ, 18 juni tijdens het Holland Festival.