It is undoubtedly one of the most alienating images we saw during the 33rd edition of the documentary festival IDFA will get to see. That sleek, snow-white, cube-shaped building that seems to have descended into the Congolese interior like a UFO. A disruptive eye-catcher in the only Dutch film in the international competition: White Cube.

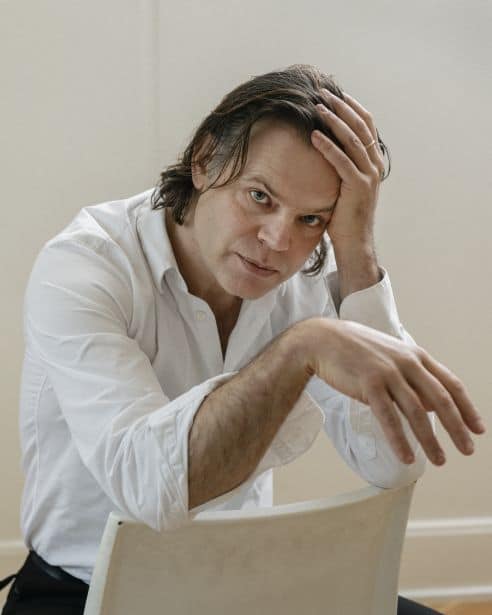

It is the new film by Renzo Martens, who already got to open IDFA in 2008 with the uncomfortable Enjoy Poverty. In it, he tells poverty-stricken Congolese that there is money to be made from pictures of their misery. Now plantation workers will sculpt for Western art lovers.

Many documentary filmmakers swear by pure viewing and recording. See, for example, the impressive testimonies of the indigenous Ayoreo in Nothing But the Sun from Paraguay, with which IDFA 2020 opens. Martens tackles it with White Cube, with colonial exploitation as a similar background, quite differently. He himself sets in motion the turmoil that becomes the subject of his film.

Art

At White Cube we see how Martens, after the photography project fiasco in Enjoy Poverty, returns again to Congo. With new plans this time to improve the lives of severely exploited plantation workers. So, should I call him a filmmaker or an activist now, I want to know as I speak to him over the phone.

"I am an artist who makes films about real projects in reality. It's an art project that might be a bit activist for other people, but that's only because I take seriously what art can do."

Can art also do something for those people in Congo?

"Art always does something for people, and as an artist you can decide where and for whom it can do something. If you make beautiful paintings and you are lucky enough to have the Stedelijk hang them, you know exactly who is going to enjoy them. That's fine, but I think art can also be about how the world works. Then I want to make sure that not only more or less rich people in affluent areas have something to gain from that art. Because our art business has been indirectly co-paid by people who are very poor, it should also be a bit nicer, nicer or better for those poor people. Just a level playing field.”

Back to Congo

You have been active in Congo for over 15 years now. How did you initially end up there?

"In 2004, I went to Congo for the first time. Before that I had been in Chechnya Episode 1 made. In Congo, I wanted to magnify what I had tried to do in Chechnya, which was to show the power relationship between people watching and people being watched. Between viewers and the people about whom films are made. People who are in misery and want to get out of it, and hope that being filmed will help."

"I wanted to portray that power relationship, and Congo just seemed like the best place to do it. It's pretty much the most difficult country in the world, with a long history of exploitation, war and disease. There is a huge symbolic weight attached to that country."

With his first Congo film, Enjoy Poverty, Martens presses our noses against the fact that it is Western photographers who earn from the misery there. Not the Congolese themselves. In White Cube he refers to the discomfort that came over him when he realised that he himself had also benefited well from the success of Enjoy Poverty.

Taking advantage of poverty

At the beginning of White Cube he even says: "I have benefited from poverty and inequality all my life. That sounds like it's not just about Enjoy Poverty goes.

"That's right. The soya we feed our pigs, the clothes we wear, the sprinkles on your sandwich, it is produced by people with a much lower standard of living than in the Netherlands. We are floating on the labour of people who are paid very, very little."

It is indeed quite shocking when in White Cube a worker on an oil palm plantation says he earns one dollar a day.

"And the women get half. All under the watchful eye of Mr Polman, CEO of Unilever. [from 2009 to 2019, LB] Human Rights Watch has written a scathing report on working conditions on those plantations: A Dirty Investment.”

Critical art

But why bother those exploited workers with an art project?

"There are a few reasons for that. First of all, I know something about art, but not about wells, nor exactly how you could improve working conditions. I am not saying that an art project is the best solution. Far better is raising wages. Maybe other people can take Unilever to court, but I can't."

"But I've been able to see for myself that if you make critical art, for example about inequality, like Enjoy Poverty, that there is a demand for it. There are exhibitions with art about war and poverty. It's just a good subject. So I thought, if those plantation workers can't live on plantation labour, maybe they can live on critical art about plantation labour. I'm a prime example of that myself."

The first project Martens undertook in White Cube undertakes, with an art conference and workshops at an oil palm plantation in Boteka, ends in failure. After she sent an email about an alleged incident of violence with machetes and spears, the plantation (a supplier to Unilever) pulls the plug.

"I was terrified. The next step is to get the army involved, and before you know it, you have a so-called ethnic war. That plantation in the beginning probably thought I was just coming there to do some fun art stuff, and I was."

"But surely those plantation workers had a bigger goal than making art. They wanted the land back that was stolen from them. They saw it as an opportunity to make that agenda visible. The company feared that might become a problem for them."

'Best art of the year'

Martens has more success two years later in Lusanga, on the site of an abandoned Unilever plantation. The people there are free. They are trying to be self-sufficient and want to make the emaciated soil fertile again. Martens starts an intriguing project there. Sculptures sculpted by former plantation workers are copied in chocolate and sold to Western art lovers. An exhibition in New York of this expressive work receives high praise in the New York Times: 'Best art of the year.'

Buy back land

With the proceeds from the chocolate sculptures, the people of Lusanga have already been able to buy back 65 hectares of land for their post-plantation project.

Meanwhile, the OMA architect-designed White Cube has also risen there, as a future museum and activity centre.

That bizarre contrast between that snow-white art temple and the former plantation, was that intentional?

"It does contrast with that old plantation, but that's just the outside. Our museums are all paid for by plantation labour."

Thus, Martens recalls in White Cube That at a screening of his film, it made him Enjoy Poverty at a London gallery, he noticed the logos of Unilever as an art sponsor everywhere.

"On top of that, from that region, all the art has been taken away, stolen, by the colonial regime and by all sorts of middlemen. Nothing is more natural than putting some back."

"In a nutshell, the White Cube project is about allowing former plantation workers to buy back land with the proceeds of their art. So that they can start ecological food forests there that they can live off themselves. The museum stands there as a kind of symbol of this whole operation."

Circle of artists

An important role in all that is played by the Cercle d'Art des Travailleurs de Plantation Congolaise (CATPC). Founded by Congolese environmentalist René Ngongo together with Lusanga's brand-new artists, including Matthieu Kasiama. In the film, they and their drive also become increasingly prominent.

"Yes, their part is the most important. If I say, 'Let's build a museum there it might be a joke.' But if they say let's build a museum to buy back the land, then it becomes interesting."

"So my role is less important," Martens notes in this regard.

"And what should happen now that that museum is there is that their stolen art should be returned. That museum there creates a kind of level playing field, so that plantation workers can also participate in those debates."

There are many more plantations that need to be bought back. You can't put a White Cube everywhere.

"And not only in Congo. No, I think much more needs to be done. Companies and museums need to start making reparations for all the money that has been sucked away there. Not just return art. I think the Stedelijk should spend their entire acquisition budget on art by plantation workers from now on. And with that money, plantation workers can buy back their land. The White Cube is an impetus for a much broader reassessment of the value chain of art."

Criticism, urgency and talent

Is there much artistic talent among the plantation workers?

Utterly: "Yes!"

"It surprised me tremendously. That it was so quick and easy. But it shouldn't surprise you that much either. Our ethnographic museums are full of evidence that those people, at least a few generations back, were incredibly talented. There used to be people making art in every village. Now they are going to do it again."

There has also been criticism of Martens' activities there. Is it the western white man again who, supported by all kinds of funds, shows how things should be done there? With good intentions, admittedly, but still.

"Yes, that criticism is definitely there and I embrace it. The film also begins with a scene in which Matthieu Kasiama remarks that he initially saw in me the returned Unilever founder William Lever."

"That said, the power may still be in the boardrooms in London, but the urgency and talent lies with plantation workers in Congo. We have an awful lot to gain from getting our ears to the ground and sharing honestly. To see their art. I think the film shows: if a white man starts to decide on his own how things should be done, things really go completely wrong. You can see that happening at the beginning in the film. You really shouldn't leave it up to someone like me, then things will go wrong."

"But when plantation workers, or people like Matthieu Kasiama and René Ngongo simply have the ability to communicate with the rest of the world, a lot of things go very well. They share with me and I share with them, that's all."

Start-up

"The White Cube is now ready to start. There has already been a kind of symbolic event in 2017, with the CATPC and people from the Netherlands, Belgium, Germany, France and America. But mostly from Congo and other African countries. Now we are waiting to see what will happen. On 21 November, the documentary White Cube er displayed."

To which Martens stresses, "The exhibitions, debates and programmes are mainly for the plantation workers. In Kinshasa and other big cities, there is already an infrastructure with many talented artists. But on the plantations, an art curator never visits, even though there is a lot of talent there too."

Returning to his film, "I especially hope that White Cube inspires. That it encourages people to just make it right together, to make it a beautiful, loving inclusive world. It's not that difficult at all. You don't have to become very poor yourself. Just share and exchange opportunities and it will all work out."

Is it conceivable that a subsequent film on this will have a Congolese creator?

"Of course, there are fantastic Congolese filmmakers. Last year, the award for best short documentary at IDFA went to Up at Night by Congolese director Nelson Makengo."

White Cube premieres simultaneously at IDFA in Amsterdam on 21 November, and in Lusanga, DR Congo. On 23 November, White Cube (with aftertalk) can be seen on VPRO. From 26 November, the film runs in cinemas. Also to be seen via picl.nl.

IDFA takes place from 18 November to 6 December, in Amsterdam and online, and in 44 film theatres across the country.