Het zijn me de personages wel, de hoofdfiguren uit de boeken van Jeroen Olyslaegers (55). Lachend vertelt hij over Wilfried Wils, de hoofdpersoon van zijn bestseller Wil uit 2016, die maar niet ophield met praten tegen zijn schepper. ‘Hij blééf maar commentaar geven. Ik had nog niet eerder meegemaakt dat een boek zo bleef leven. Toen het boek werd bekroond met de Ultima 2016 voor de Letteren, een belangrijke Vlaamse cultuurprijs, werd me gevraagd of ik voor het promotiefilmpje een brief wilde schrijven aan een overleden schrijver. Ik stelde voor een brief te schrijven aan mijn hoofdpersonage, dat leek me toepasselijker. Daarin heb ik hem gevraagd, allez, zwijg nu. Daarna was het afgelopen.’

Maar rustig is het allesbehalve in het hoofd van de Belgische auteur. Want inmiddels is die plek in beslag genomen door Amandine, de hoofdpersoon van zijn volgende roman, getiteld De wonderen in de waan, en een belangrijk personage in zijn net verschenen novelle Willem en mijn wellust. Olyslaegers noemt deze novelle als het ware een koppelteken tussen zijn vorige roman Wildevrouw en De wonderen in de waan. Waarmee niet is gezegd dat het maar een tussendoortje is, want Willem en mijn wellust is een intrigerende, beeldend en bloemrijk geschreven novelle, die als verhaal prima op zichzelf staat.

Zestiende-eeuws Antwerpen

Net als Wildevrouw speelt het verhaal zich af in zestiende-eeuws Antwerpen, waarin boekdrukker Willem Silvius samenwerkte met de welbekende meesterdrukker Christoffel Plantijn. Tijdens de beeldenstorm van 1566 werd Silvius gevangengezet, omdat hij werd verdacht met protestanten te hebben samengewerkt. In de nor schrijft Silvius brieven aan zijn echtgenote. In 1885 komen deze brieven in handen van feuilletonschrijver Hippolyte van Damme, die ze steelt van een antiquaar. Hippolyte denkt goud in handen te hebben voor zijn feuilleton, maar al snel weegt het bezit na de diefstal als lood op zijn schouders. De bekentenis van de diefstal aan zijn minnares Amandine en zijn zwijgen erover tegen zijn vrouw Catharina splijten zijn leven in tweeën. Wat is diefstal, wat is (seksueel) bezit, hoe verslavend is bezit, welke verschillen bestaan daarin tussen man en vrouw – dat zijn enkele thema’s in dit boeiende verhaal, dat niet alleen een brug slaat tussen twee grote romans, maar ook tussen de zestiende en negentiende eeuw.

U zei: Willem en mijn wellust is het koppelteken tussen Wildevrouw en uw volgende roman. Hoe zit dat precies?

‘Dit verhaal komt voort uit die vorige roman, en introduceert Amandine, het hoofdpersonage in mijn volgende roman. Wildevrouw speelde zich af in het Antwerpen van de zestiende eeuw, een periode van grote bloei op zowel het gebied van de handel als op artistiek en cultureel gebied. Die situatie keert pas terug in de negentiende eeuw, maar dan zonder de artistieke bloei. België koopt in de negentiende eeuw de toevoer van de Schelde terug van Nederland en dan breekt er een tijd van grote welvaart en bloei in handel aan in Antwerpen.

Amandine komt uit een bankiersfamilie, die dan natuurlijk goede zaken doet. We zitten dan ook volop in de koloniale periode, met de exploitatie van Congo. De macht is dan in handen van francofone Belgen, dus de mensen die Frans spraken. Al die aspecten maken, vind ik, de tweede helft van de negentiende eeuw in de Belgische geschiedenis heel interessant. De roman gaat heten De wonderen in de waan, waarbij “waan” staat voor het ver doorgeschoten materialisme en “wonderen” voor het irrationele, de magie, seances en hekserij, het paranormale. Want dat krijgt eveneens een renaissance in de negentiende eeuw. Zoals Louis Couperus met zijn Eline Vere schreef over vrouwelijke hysterie, gaat deze roman over mannelijk hysterie. Daarvoor ga ik alle clichés van die tijd gebruiken: de femme fatale, iemand die wordt gehypnotiseerd, een seance, iemand die een opiumpijp voor de eerste keer probeert.’ Olyslaegers lacht: ‘En natuurlijk véél bordelen.’

Maar hoe diende zich dan deze novelle aan als ‘koppelteken’?

‘Met De wonderen in de waan was het voor het eerst dat ik een vrouwelijke hoofdpersoon hoorde. Maar Hippolyte van Damme drong zich aan mij op, hij vond dat hij ook iets te vertellen had. Een mannetje dat ertussen kwam en nog snel een glansrol voor zichzelf wilde opeisen.’

En u dacht: die geef ik hem dan maar.

‘Ja, ik vond dat hij daar wel recht op had. Ik had al een paar scènes geschreven van mijn roman, en een aantal daarvan spelen zich af in een bordeel. Daar zag ik die Hippolyte van Damme een coupe de champagne bestellen en ik dacht: misschien toch wel een interessante kerel.’

Vindt u het belangrijk uw landgenoten iets te leren over de Belgische geschiedenis?

‘Soms. Maar ik ben ook maar een charlatan, dus die moraliteit ga ik mijzelf niet toeschrijven. Er zijn alleen zulke fantastische verhalen die nog niet verteld zijn, waar niemand wat mee doet. Dus daar ligt voor mij een kans. Als ik aan een roman begin, stel ik altijd domme vragen. Bij De wonderen en de waan was de beginvraag: wanneer wisten Belgen af van de gruwelijkheden die plaatsvonden in Congo vanwege de winning van rubber? Door onderzoek kwam ik te weten dat dit al vanaf april 1900 het geval was. Wanneer ik dat aan iemand vertel, reageert iedereen: hoe kan dat nou? Vervolgens vraag ik me af: als je weet welke wandaden daar plaatsvinden, wat doet dat dan met je geweten? Hoe ga je daarmee om? Schuldgevoel is een thema dat ook heel interessant is in onze huidige tijd. Veel mensen, vooral die uit progressieve kringen, voelen zich schuldig over van alles, bijvoorbeeld het feit dat ze wit zijn. Zij dragen de loden mantel van de geschiedenis van exploitatie op hun schouders.’

Apocalyptisch denken

Wat fascineert u het meest aan het einde van de negentiende eeuw, het fin du siècle?

‘Allez, keer op keer als ik onderzoek doe naar die periode, zie ik dat er ook toen al een apocalyptisch denken was. Wij denken nu dat onze aanwezigheid op deze planeet problematisch is geworden, maar dat is iets wat mensen al heel vaak hebben gedacht: nu is het einde der tijden nabij. In de hogere kringen bestond ook toen al onbehagen over de mate van consumeren. Ook toen al waren er problemen met identiteit en gender.’

Wat kunnen wij daar nu van leren?

‘Dat geschiedenis en een samenleving circulair zijn. Keer op keer worden we geconfronteerd met dezelfde problemen. Of we daar iets van kunnen leren, weet ik niet, maar misschien biedt het wel enige troost. Mij in ieder geval wel. Onze huidige situatie is niet zo exceptioneel, een eeuw geleden was het ook al zo.’

Is uw eigen denken over onze plek op aarde veranderd?

‘Dat denk ik wel, ik ben meer gaan relativeren. Toen ik Wil aan het schrijven was, vond mijn hoofdpersoon Wilfried Wils het woord “normaalzucht” uit: de menselijke neiging of behoefte om een zo normaal mogelijk leven te leiden, zelfs in abnormale tijden. Daar zit een grappige en een tragische kant aan. We leven nu in tijden waarin niks nog echt normaal is; denk maar een paar seconden na over de toestand in de wereld. Ik begin daar meer en meer vrede in te vinden, en van dag tot dag te leven. Ik heb zeker troost gevonden in de wetenschap dat er ook al in de zestiende eeuw een heleboel mensen waren die er absoluut van overtuigd waren dat het Laatste Oordeel, het oog in oog staan met God, zou plaatshebben in 1582, met een datum en al. Cartograaf Gerardus Mercator bijvoorbeeld was zo iemand. Juist in apocalyptische tijden steken we nog meer energie in die normaalzucht. We gaan meer escapisme meemaken dan ooit. HBO, Netflix en Amazon Prima steken miljarden in het produceren van series. We zullen worden omsingeld door fictie.’

U houdt zich bezig met boeddhisme en meditatie. Hoe kijkt u vanuit dat perspectief tegen dit fenomeen aan?

‘Overal in de openbare ruimte in de stad zie je dat mensen mentaal zijn afgesloten en niet meer kijken naar dat wat hen omgeeft. Iedereen loopt met oortjes in. Wat ik daar vooral in ontwaar, is de behoefte om absolute controle te hebben over wat in je hoofd gebeurt. We worden opgeslorpt door wat we zelf hebben gekozen: mijn playlist, mijn Spotify, mijn Instagram feed. Mijn, mijn, mijn. Het is escapisme in onze eigen particuliere wereld. Meditatie leert je juist dat controle een illusie is. Dus dat is waar ik vooral aan denk als ik mensen zich zo zie afsluiten van de wereld: dat wordt een ruw ontwaken.

We leven in apocalyptische tijden, in de betekenis van onthullend. Onthulling is belangrijk in mijn werk. In Willem en mijn wellust komt Hippolyte van Damme ook tot een paar genadeloze inzichten. Zoals de illusie van bezit. Hij wordt in feite een gevangene van zijn bezit van de gestolen brieven.’

Olyslaegers neemt een slok van zijn blonde biertje en kijkt even peinzend voor zich uit. ‘Ik hoop overigens dat het duidelijk is voor de lezers dat Amandine niet is hoe zij door Hippolyte van Damme wordt afgeschilderd. Voor hem is zijn minnares een mysterie en toont ze zich op het einde genadeloos en wreed. De grotere roman zal meer draaien om háár levensgevoel.

Ik heb nu een scène voor ogen waarin ze kijkt naar haar kind, dat net rechtop kan zitten op het tapijt. Ze beseft dat het dragen en baren van dit kind eigenlijk haar enige taak was: zorgen voor een erfgenaam. Haar vrouwenhart zegt dan: dit moet ik allemaal zien te overleven, deze door mannen gedomineerde wereld waarin zijzelf niet meer is dan een ornament. Ze moet mooi zijn, zwanger worden, een toegewijde moeder zijn en anderen entertainen – alles wat ze doet ten dienste van haar man. Wat gebeurt er dan met iemand die geboren is met een onafhankelijke geest? Zulke vrouwen zijn er in alle eeuwen geweest, maar daar vernemen we weinig over, want de meerderheid van die vrouwen is verdwenen in de geschiedenis.’

Bijvoorbeeld doordat ze werden weggezet als hysterisch en vervolgens werden opgesloten.

‘Ja. Sommige mensen hadden het idee dat er een heks zit in elke vrouw, struggeling to get out. Die patriarchale repressieve samenleving waarin zogenaamde heksen worden uitgeroeid, komt terug in de negentiende eeuw en heeft invloed op het vrouwbeeld. Aan de ene kant wordt zij beschouwd als satanisch en dus zeer fout maar ook zeer aanlokkelijk, aan de andere kant wordt van de zogenaamde witte heks een standbeeld gemaakt als ware zij de enige overlevende van een heidense cultuur. Beiden zijn clichés, die ik ga loslaten op Amandine, en dan maar zien wat er gebeurt. Ik zie het boek als een eerbetoon aan mijn moeder. Zij was een echte feministe, maar niet op een indoctrinerende manier. Ik heb haar altijd erg bewonderd vanwege de rustige standvastigheid waarmee dat ze haar feministische standpunten over het voetlicht bracht en meende dat mannen daar natuurlijke partners in zijn. Zij lachte een man die zei dat hij feminist was, niet uit.’

U heeft niet eerder vanuit vrouwelijk perspectief geschreven. Waarom eigenlijk niet?

‘Ik was nog niet matuur genoeg, nog niet volwassen. Bij mij heeft de #MeToo-beweging er flink ingehakt; ik ben over veel dingen anders gaan denken, doordat ik me bewuster ben geworden van de verschillen tussen een mannelijk en vrouwelijk perspectief. Zeker in de negentiende eeuw hadden vrouwen geen stem. Neem de literatuur: we hebben Madame Bovary, Eline Vere en Anna Karenina. Alle drie de boeken gaan over een getroebleerde vrouw, zijn geschreven door een man en eindigen tragisch. Dat geeft wel een heel specifiek beeld van de vrouw, en dan zijn het ook nog eens dé boeken die de romankunst definiëren.

Ik wil scènes schrijven waarin Amandine fantasieën heeft waarin ze haar echtgenoot een aframmeling geeft. Ze leeft in een voor haar verkeerde tijd, heeft veel last van verveling. Maar wat er precies gaat gebeuren weet ik nog niet.’

Dat zal Amandine u zelf wel vertellen?

‘Ja, dat denk ik wel. Soms zit ik in de tuin en hoor ik heel duidelijk haar stem, dan vertelt ze me een hele paragraaf en hoef ik die alleen maar op te schrijven.’

Jeroen Olyslaegers, Willem en mijn wellust (112 p.), De Bezige Bij, € 18,99

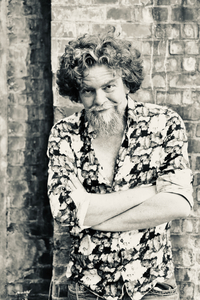

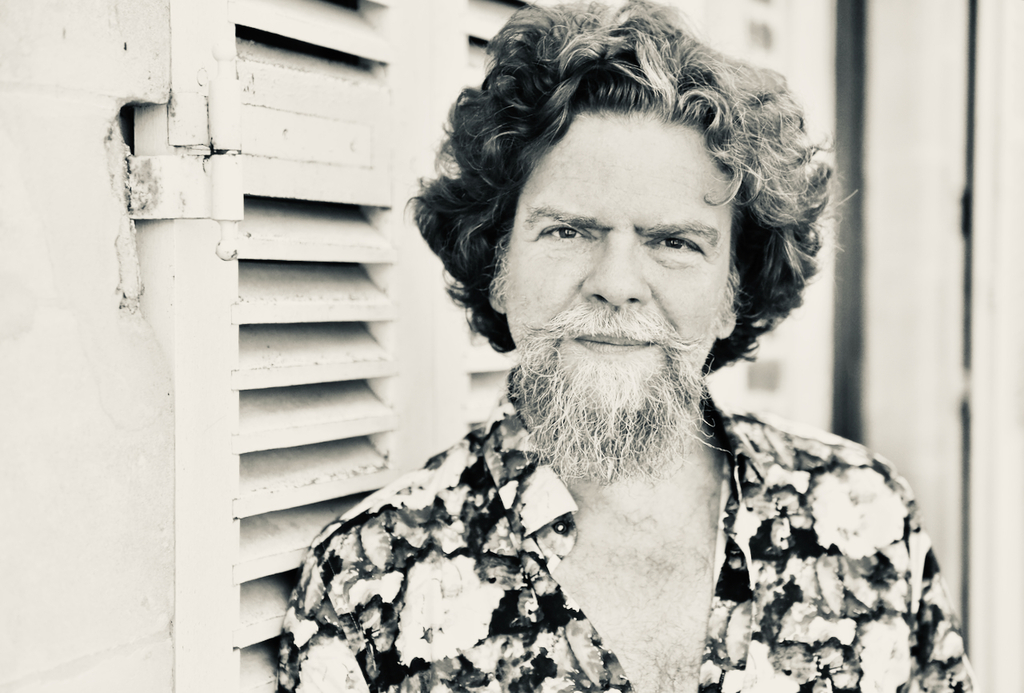

Over Jeroen Olyslaegers

De Vlaamse auteur Jeroen Olyslaegers (1967) is schrijver van romans en toneelwerk. Hij debuteerde in 1994 met de roman Navel. Naast artikelen en recensies voor media als Humo, De Vlaamse Gids en Maatstaf schreef hij onder meer Woeste hoogten, rusteloze zielen, een theaterstuk gebaseerd op het werk van Emily Brontë. Na de romans Wij (2009) en Winst (2012) brak hij door naar het grote publiek met de roman Wil(2016). Het boek werd veelvuldig bekroond, onder meer met de Fintro Literatuurprijs en de F. Bordewijk-prijs. Hierna volgde de historische roman Wildevrouw (2020). Eind oktober verschijnt de novelle Willem en mijn wellust, een voorproefje van de nieuwe roman waar Olyslaegers aan werkt.