De 52ste editie van International Film Festival Rotterdam (IFFR) opent 25 januari met Munch van de Noorse filmmaker Henrik Martin Dahlsbakken. Een prachtig psychologisch portret van de met het leven worstelende Edvard Munch, de kunstenaar die bekend zou worden als schepper van De Schreeuw. Vier acteurs spelen de schilder in vier bepalende episoden van Munchs leven. Dahlsbakken monteert dit als een mozaïek dat het verhaal een extra zeggingskracht geeft. Munch kan gemakkelijk een breed publiek aanspreken, maar toont tegelijkertijd Dahlsbakken als een filmmaker met een eigen stem.

Een mooie start van een festival dat juist die eigen stem hoog in het vaandel heeft staan. En dat daarnaast nog best een stapje verder wil gaan door werk te laten zien dat de grenzen van de cinema en verbindingen met andere kunstvormen opzoekt. Zoals in het programma-onderdeel Art Directions.

‘Film is filmkunst is kunst’, is de in dit verband vaak aangehaalde uitspraak van Hubert Bals, de aartsvader van IFFR. Want film mag dan een geweldig verhalend medium zijn, de kracht en expressie zijn daarmee niet uitgeput. Ook buiten het programma Art Directions zijn daar genoeg voorbeelden van te vinden.

Film als een muziekstuk

Zie bijvoorbeeld Nummer Achttien – geselecteerd voor de Tiger Competitie – van de Nederlandse filmmaker Guido van der Werve. Iemand die zich vaak beweegt op het vlak tussen beeldende kunst, performance en film. Na een ernstig ongeluk dat bijna zijn dood werd blikt hij in Nummer Achttien terug op zijn leven.

Docufictie noemt hij dit tegelijkertijd droog-poëtische en stil-ontroerende zelfonderzoek. Beelden van zijn revalidatie wisselt hij af met nagespeelde fragmenten uit een moeilijke jeugd. Tot zover niet bijzonder ongewoon van opzet, tot plots een muziekgezelschap met koor de scène binnenstapt en zorgt voor een gezongen overpeinzing. Wat heel iets anders is dan een musical. Daarbij krijgen ook de schilderijen van Guido’s vader ook een belangrijke rol toebedeeld. Zo stijgt Nummer Achttien uit boven de geijkte formules en zou je het misschien een visueel muziekstuk kunnen noemen waarmee hij zijn gevoelens op een bijzondere manier tot uitdrukking brengt.

Uitdagende animatie

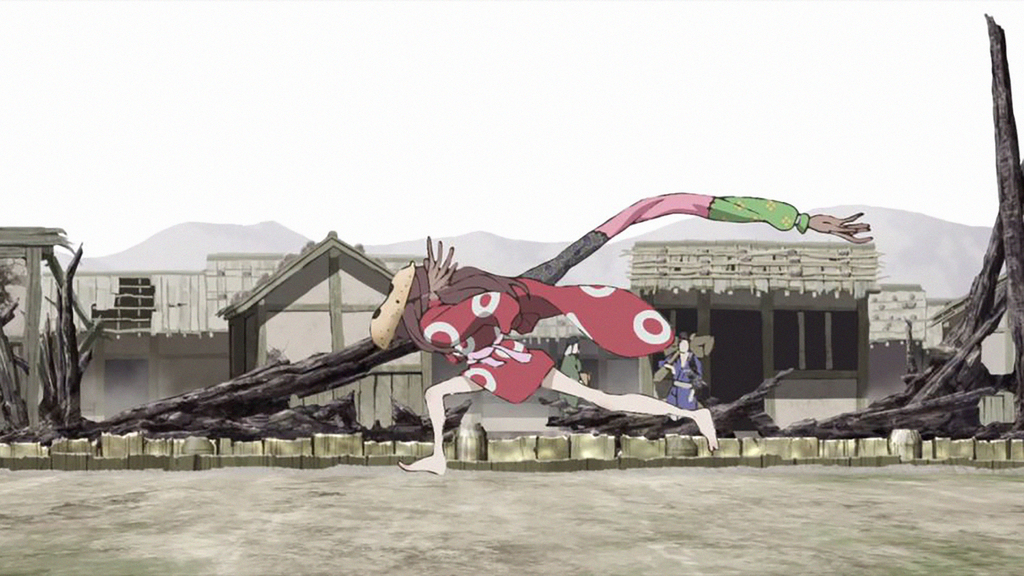

Als het gaat om verbindingen met beeldende kunst vinden we in het domein van de animatie ook veel van onze gading. Een van de filmmakers in focus op het IFFR is de Japanse animatieregisseur Yuasa Masaaki, hard op weg naar een vergelijkbare status als die van Hayao Miyazaki. Zijn nogal conventioneel ogende Ride Your Wave (twee jaar geleden in de Nederlandse bioscoop) blijkt achteraf een uitzondering in zijn oeuvre vol uitdagende uitspattingen.

Vol verbazing en met groeiend enthousiasme heb ik gekeken naar zijn nieuwste film Inu-oh. Een opstandig avontuur, ook als film, over de lotgevallen van een non-conformistisch zang en dansduo in het veertiende-eeuwse Japan. Visueel spectaculair, met taferelen die nu eens refereren aan klassieke Japanse prenten, dan weer aan moderne grafische collagekunst of eigentijdse rocksterren. Uitbundig, brutaal animatie-expressionisme. Zijn al even ongeremde debuut Mind Game is ook op het IFFR te zien.

Politieke collagekunst

Een ander focusprogramma is gewijd aan de Amerikaanse kunstenaar Stanya Kahn. Ook zij overschrijdt de artistieke grenzen met animatie en performance, muziek en schilderkunst, fictie en documentaire. In So Low You Can’t Get Over It gebruikt ze bijvoorbeeld eigen schilderijen als grondstof voor een even wondermooie als geheimzinnige, ultrakorte digitale animatie. Ronddrijvende figuurtjes staren op hun mobiele telefoons in een abstract, voortdurend veranderend landschap.

Haar Stand in the Stream is dan weer volstrekt anders, maar lijkt toch ook te zoeken naar een onderliggend gevoel in een verwarrende wereld. Documentaire collagekunst zou je het kunnen noemen. Dus geen traditioneel documentair betoog over een recente ontwikkelingen. Wel een onderdompeling in een maalstroom van beelden, van de protesten op het Egyptische Tahrirplein tot de verkiezing van Trump, geïnspireerd door een citaat van Bertolt Brecht. Meeslepend, urgent en politiek. Blijf overeind in de maalstroom, laat je gelden!

Art Directions

Bij het zoeken naar de kunstvorm cinema ook kan zijn gaat het programma Art Directions dan nog weer een stapje verder. Zoals twee jaar geleden al eens de opzet was van Vive le cinéma, het gezamenlijke jubileumprogramma van Eye en IFFR. Weg van de traditionele vertoning in de bioscoopzaal. Dat kan Virtual Reality zijn, maar ook film of videobeeld als onderdeel van een kunstinstallatie of audiovisuele performance. Soms live, soms als een multi-screen-presentatie, soms als een ruimte waarin je als bezoeker onderdeel wordt van het project.

Bezoekers van IFFR kunnen nu bij aankomst op Rotterdam Centraal Station direct al binnenstappen in de installatie Æther (Poor Objects). Het belooft een poëtische onderdompeling waarin de digitale vloggerwereld verbonden wordt met beelden van een zonsverduistering. Twee uitersten van ongrijpbaarheid, stel ik me zo voor, want ik was nog niet in de gelegenheid het zelf te zien.

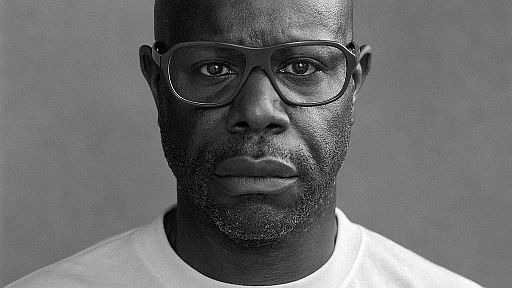

Nieuwsgierigmakend is Art Directions in ieder geval wel, en dat geldt beslist voor de nieuwe video-installatie Sunshine State van Steve McQueen. Hij verwierf zijn bekendheid vooral als regisseur van films als Oscarwinnaar 12 Years a Slave, het in Cannes bekroonde Hunger en de betrekkelijk recente serie Small Axe met verhalen uit de Caribische gemeenschap in Londen.

Maar voor hij filmmaker werd liet McQueen zich al gelden als beeldend kunstenaar. Twee disciplines die samenkomen in de op uitnodiging van IFFR gecreëerde installatie Sunshine State, opgesteld in Depot Boijmans Van Beuningen. Het festival noemt dit zich op twee schermen afspelende videoproject een ‘monumentaal werk dat uitnodigt tot reflectie’. Fragmenten uit de eerste sprekende film The Jazz Singer (1927), gaan daarin samen met een schokkend verhaal over een racistisch incident dat McQueens vader meemaakte, en beelden van een vurig brandende zon. Ik ga het zeker zien.