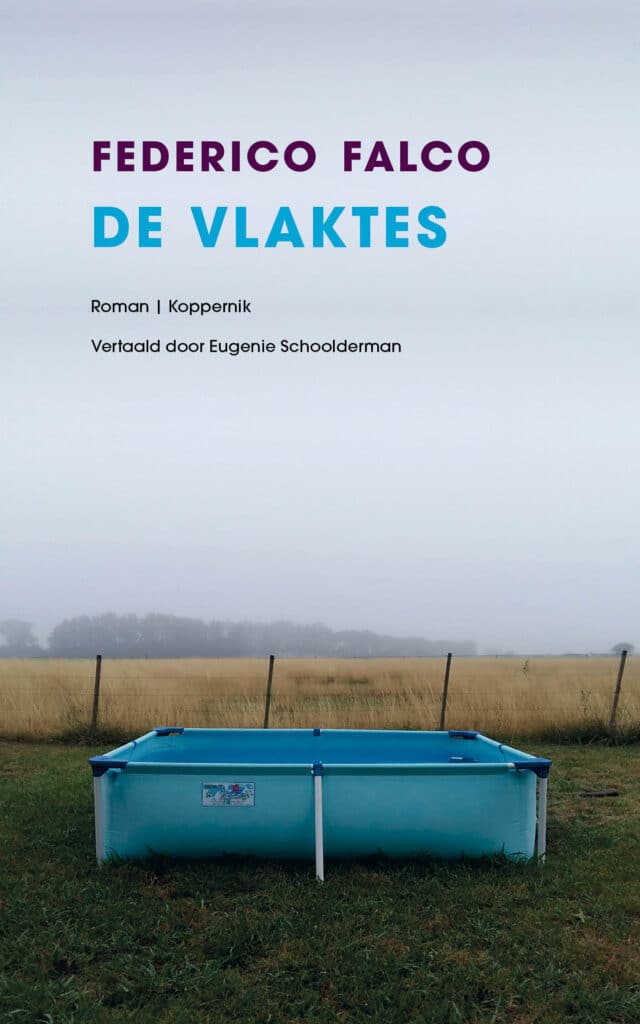

In De vlaktes van de Argentijnse schrijver Federico Falco keert een schrijver na de breuk met zijn geliefde terug naar het leven op het land. Dat levert een mooie, weemoedige roman op over rouw, oorsprong en de aard van het leven zelf.

‘Geen enkel woord temt het verdriet. Geen enkel woord verdrijft het. Geen enkel woord kan het echt uitdrukken.’ Die gedachten bekruipen de ik-verteller in De vlaktes, een schrijver die ontdekt dat taal – dat wat hem altijd grip gaf op de werkelijkheid – geen troost biedt voor het verdriet dat hem kwelt nadat zijn vriend Ciro hun relatie heeft beëindigd.

De tweeënveertigjarige schrijver Fede (een afkorting van Federico) is een achterkleinzoon van een Italiaan die vanwege de Eerste Wereldoorlog Piëmonte ontvluchtte en zich op de Argentijnse pampa vestigde. Stukje bij beetje maakten de overgrootvader en grootvader van de ik-verteller de aarde bruikbaar voor het telen van groente en andere gewassen. Maar ‘het beloofde land’ bleek een onbarmhartige, moeilijk te vullen leegte. Fede voelde zich als adolescent verstikt in die omgeving. Als schrijver en als jongen die op jongens viel, kon hij daar nooit echt zichzelf zijn.

Dat gevoel er nooit bij te horen, geen plek te hebben, verdween pas toen hij in Buenos Aires een relatie kreeg met Ciro. En juist daarom is de wond ook zo diep als Ciro na jaren nogal plotseling de relatie verbreekt.

Omdat schrijven niet meer lukt, neemt de verteller zijn intrek in een huisje op het platteland om daar een moestuin aan te leggen. Graven, spitten, zaaien, onkruid wieden, zaaibedden aanleggen – dat helpt om zijn hoofd leeg te maken en zijn gedachten te ordenen.

De dagen rijgen zich aaneen met het werk op het land, terwijl de weertypen en seizoenen verglijden. Net als zijn opa ‘dansend op het ritme van de muziek van het oogsten’, geeft het fysieke werk hem tijd voor reflectie op zijn relatie, zijn oorsprong, het leven en zichzelf.

Innerlijk landschap

De vlaktes doet qua stijl en thematiek denken aan auteurs als Cynan Jones en Jesús Carrasco. Niet de gebeurtenissen zijn leidend; de schoonheid van deze roman zit ‘m in de verfijning van de waarnemingen en de beschrijvingen van het innerlijke en uiterlijke landschap.

Falco’s zinnen zijn afgemeten, ontdaan van franje, en vaak onpersoonlijk geformuleerd, alsof de dingen slechts benoemd of opgesomd worden: ‘Aarde op je huid, aarde in je haar, stof in je oren, op je lippen, in je neus, op je tanden. Snot dat hard en zwart wordt. Het maisveld. De maisbladeren, hard, scherp en ruw als schuurpapier.’

Gaandeweg het verhaal, als de scherpste randen van het verdriet beginnen af te slijten, worden ook de zinnen zachter, ruimer. En wordt de diepte voelbaar die eronder verborgen ligt.

Het leven vorm geven – letterlijk, met de handen in de aarde; figuurlijk, in woorden en verhalen – blijkt toch een manier om rust en vrede te vinden. Geen enkel woord kan het verdriet echt uitdrukken, zegt de ik-verteller. Maar met alle woorden die samen dit verhaal vormen is de schrijver daar toch in geslaagd.

Vertaald uit het Spaans door Eugenie Schoolderman

Koppernik, € 24,50