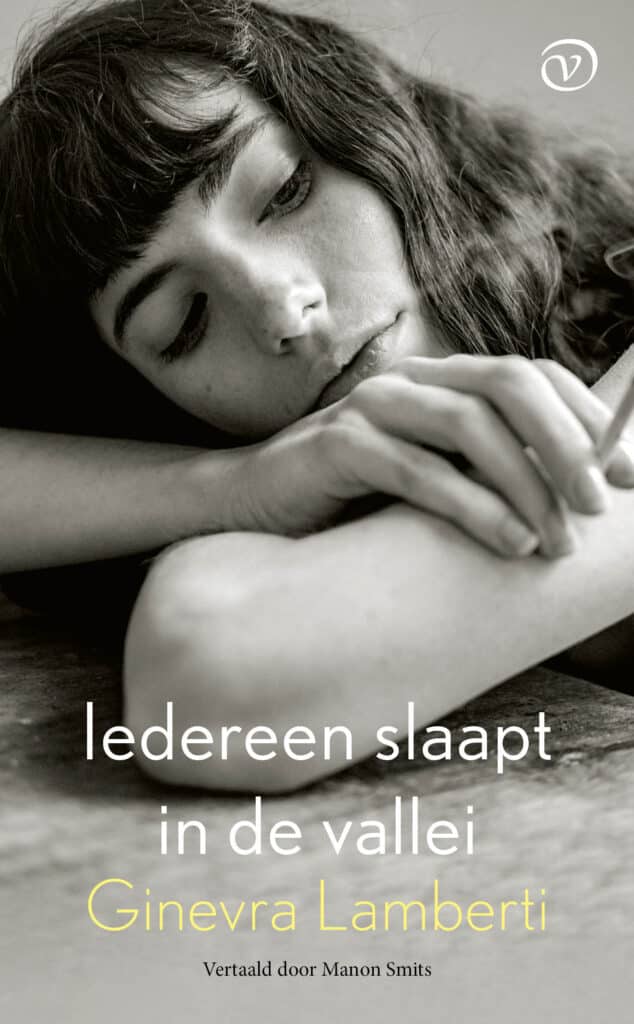

Als vakantiebestemming zijn de groene, weidse Italiaanse valleien heerlijk, maar op een dergelijke plek léven is minder idyllisch, toont Ginevra Lamberti in haar roman Iedereen slaapt in de vallei.

‘De vallei is geen plek maar een tijd waar geen eind aan wil komen, het leven hier is geen tijd maar een plek waarvan de uitgang niet te vinden is.’ Die niet al te positieve gedachte bekruipt de jonge Italiaanse vrouw Gaia, die in ‘het gele huis’ woont in een stille vallei in de regio Veneto. Het is de plek waar haar voorouders ook opgroeiden en woonden, en waarnaartoe iedereen altijd weer terugkeerde.

Zo ook Gaia, die tevergeefs in Rome heeft geprobeerd te slagen in het leven – opleiding, werk, relaties – en vervolgens terugkeert naar de vallei, naar het gele huis waar haar oma en ouders nog steeds wonen. Dat voelt als falen. ‘Nu ze hier terug is fluistert de wind elke nacht tegen haar dat ze heeft verloren.’

Oorspronkelijk

Iedereen slaapt in de vallei is Ginevra Lamberti’s derde roman en de eerste die in het Nederlands is vertaald. Met haar eerdere twee boeken vestigde zij al meteen haar naam als nieuw literair talent; haar vorige, Perché comincio alle fine, werd bekroond met de Premio Mondello voor de oorspronkelijkheid van het verhaal en de originele vertelwijze.

Lamberti kneedde voor deze nieuwe roman autobiografische elementen tot fictie: net als Gaia werd ze geboren in de grootste afkickkliniek van Europa, San Patrignano, en groeide ze op in de beschreven vallei. Die levensechtheid is voelbaar en maakt het geschilderde landschap en de personages authentiek, al roepen ze niet direct warme gevoelens op.

Drie generaties

Tegen de achtergrond van het veranderende Italië schetst Ginevra Lamberti in Iedereen slaapt in de vallei het leven van drie generaties vrouwen: Augusta, haar dochter Costanza en Costanza’s dochter Gaia. Augusta is nog maar een meisje als ze uit werken wordt gestuurd. Haar broers mogen doorleren, maar in de jaren voor de Tweede Wereldoorlog is dat voor meisjes in grote, armere gezinnen uitgesloten.

Opgegroeid in het gele huis in de besloten vallei, waar het begin en het einde van de dag ‘onthoofd’ wordt door de bergen, krijgt ze een cultuurschok te verwerken als ze naar Milaan wordt gestuurd om op het driejarige dochtertje te gaan passen van een welgestelde weduwnaar, die een ander leven is begonnen. Ze krijgt per maand minder betaald voor de zorg voor het meisje dan de prachtige pop kost die ze aantreft in de etalage van een speelgoedwinkel. Augusta plooit zich naar de verwachtingen van de buitenwereld en stopt haar eigen verlangens en gevoelens weg. Dat maakt haar als volwassene tot een stuurse, kille vrouw.

Als Augusta na terugkeer naar het ouderlijk huis maar geen aanstalten maakt een eigen leven te beginnen, beloven haar ouders haar ten huwelijk aan de twintig jaar oudere weduwnaar Tiziano. Tegen heug en meug wordt daaruit dochter Constanza geboren: Tiziano wilde eigenlijk een zoon, Augusta alleen maar een pop. Ze beschouwt de vleselijke plicht en het resultaat daarvan als een vloek.

Jaren zeventig

Costanza groeit tamelijk eenzaam op in een liefdeloos gezin. Maar het gebrek aan emotionele betrokkenheid heeft ook zo z’n voordelen: dat biedt haar de mogelijkheid om met haar vriendin Livia zo vaak mogelijk te ontsnappen naar de stad. Want daar waar de tijd in de vallei lijkt stil te staan, zijn in de rest van de wereld de jaren zeventig aangebroken met zijn hippies en drugs.

Zowel Livia als Costanza zoeken hun heil in een relatie, maar komen bedrogen uit. Livia wordt jong moeder, maar blijft later alleen achter. Costanza krijgt een relatie met Claudio, die ernstig verslaafd is aan heroïne. Toch zegt ze hem niet vaarwel, sterker nog, ze volgt hem naar een nieuwe, commune-achtige afkickkliniek, waar verslaafden de kans krijgen hun leven weer op de rit te krijgen, maar zich moeten onderwerpen aan strenge regels.

Zo kan het gebeuren dat Costanza de baas van de kliniek zover krijgt om haar dochtertje Gaia terug te laten gaan naar Augusta en het gele huis in de vallei, terwijl Claudio en zijzelf in de kliniek moeten blijven.

Als ze uiteindelijk toch weg mogen, breekt een roerige tijd aan waarin Costanza depressief is, Claudio steeds meer paranoia raakt en het ‘gezin’ aldoor verhuist, om uiteindelijk terug te keren naar het hele huis in de vallei. Die nog leger en verlatener lijkt dan ooit, sinds de moderniteit de vorm heeft aangenomen van een snelweg in de verte.

Voorouders

In hoeverre wordt een mens bepaald door zijn voorouders en de omgeving waarin hij leeft? Om die vragen draait het in Iedereen slaapt in de vallei. De gefragmenteerde wijze waarop Lamberti haar hoofdpersonen introduceert en gebeurtenissen beschrijft, steeds weer verspringend in de tijd, vraagt concentratie van de lezer.

Maar die vertelwijze reflecteert ook op een knappe manier de gefragmenteerde, niet erg benijdenswaardige levens van de personages, die vooral bestaan uit zorgen voor anderen. Gaia’s verzuchting dat ‘bloedbanden eigenlijk wettelijk verboden zouden moeten worden’ komt dan ook niet uit de lucht vallen.

Gelukkig gloort er aan het einde van deze mooi vertelde, maar weinig vrolijk stemmende roman wel een sprankje hoop.

Vertaald door Manon Smits.

Van Oorschot, € 25,–