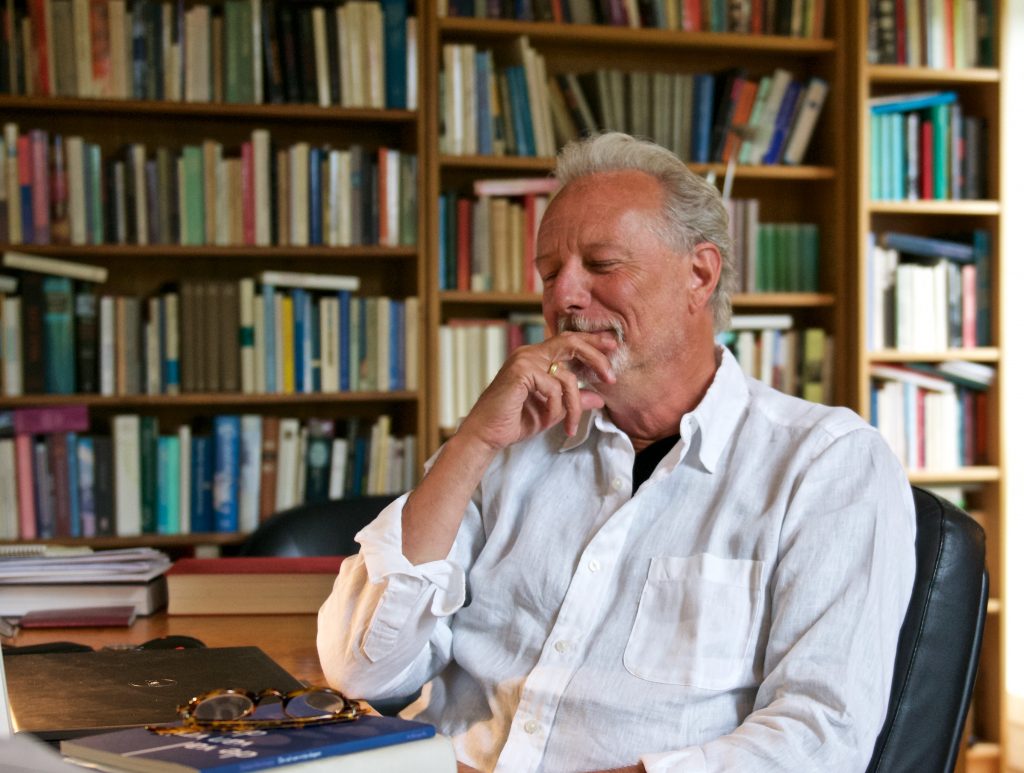

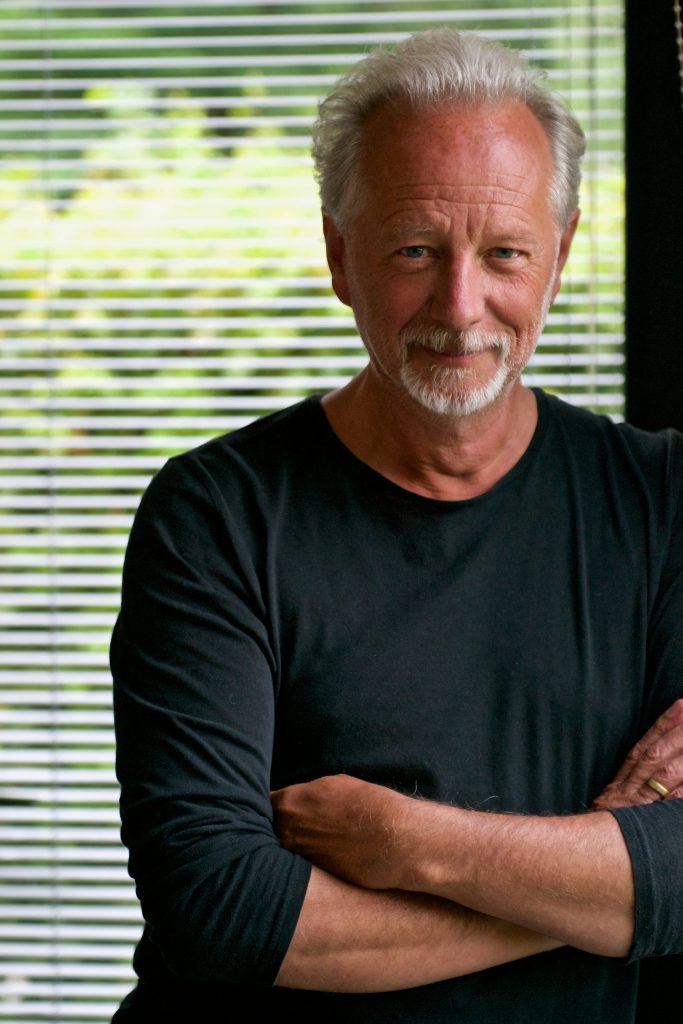

His two internationally successful novels as War and turpentine and The convert bring Stefan Hertmans all over the world. But the social side of life it clashes with his desire for solitude. Six life questions to Flemish author Stefan Hertmans. 'When I am alone, I find myself.'

1. What is your recurring dream?

'For fifty years, I have had the same nightmare every other week. I look from above onto a square teeming with ants. In the middle is a pole, and one ant keeps walking to that pole and back. It drives me crazy.

Each time I woke up sweating - the chills still run down my spine now. I think the dream is about insecurity. I always struggled with being known, I didn't want to be that one ant, I just wanted to stay among the other ants. I remember when I was seventeen and at the atheneum in Ghent. I was on the editorial board of the school paper and had written a poem on the death of Stijn Streuvels. My English teacher was married to Streuvels' daughter. When I entered the classroom, he said, somewhat ironically, "Boys, there is a poet among us." I was dying of misery. There I was that ant by that pole. That was the first time writing made me feel lonely. I felt excluded.

I have come to terms with being someone who is looked at. The constriction has ceased; I am calmer in my life. Maybe that's why I haven't had the dream for a long time.'

2. What is the biggest lack in your life?

'I have been writing since I was 14, but actually I had wanted to be a musician. I played guitar and I was good at that; I probably could have played in pop bands all my life, and I would have become an old rocker. [laughs] But I wanted to play jazz and classical. I cut my teeth on that: I couldn't read the scores well enough. When I saw how talented my brother was, I quit. He had real talent: he became one of the greatest jazz musicians in our country.

I eased the pain by starting to write. My writing became largely compensation for the lack of music - I had wanted to have a grand piano in my house and be able to play Bach. When my brother plays music, I still have very strong emotions. He can play anything, he breathes music. I envy that. I cannot complain about what I have done in my life. But if I could have chosen, it would have been music. That's the highest thing for me.'

3. When was the last time you were very angry?

'Just yesterday. My wife Sigrid wanted something a certain way, our son wanted it differently and I wanted it even differently and then the three of us are in the oedipal triangle. We each then feel that the other does not understand us. Sigrid can get very angry, but puts it off quickly. I stay simmering longer in my anger. Sometimes I shout, "I'm going to live alone now!" I need to leave, to be alone, only then will I regain my balance. As long as I stay, I stay angry.

You should get angry about the right things in life, I think. So not for trivialities, or because you are impatient or tired, or not in tune with something. In that, you have to learn to control yourself, although it is not simple. Anger over moral issues, politics, injustice in the world I think is a good anger, but anger in love is destructive. When I am angry, I suffer. It makes me sick. I don't function in disharmony.

Perhaps that is because I grew up with a great illusion of harmony. I say "illusion" because I am sure it was not as harmonious as I thought. But I am always striving for a lost paradise. I cannot stand injustice and have a great talent for indignation, even at something as trivial as a traffic situation. At quiet moments, I can laugh at myself, but at times when I am in a bind, I cannot relate. The do-gooder in me gets really pathetically angry.'

4. What is the secret of good sex?

'Emotion. Ideal sex is sex in love, where you both feel like you have to and that it is exclusive: only we can do this with each other that way.

I increasingly feel that sexuality is the only true transcendence of human beings. Together you can touch the perfect, rise above yourself. I also increasingly believe in Marvin Gaye's Sexual Healing: that sexuality is the most important healing force in life. I imagine you can have good sex with any person. I have nothing against that - I am not a moralist. But if you ask me what I find most perfect, what brought me the most happiness, it was the moments when everything coincided with my lover and we experienced the same emotion and energy.

Such intensity is not the same as exuberant fervour; it can also be quiet and watchful. It is about attention, about beauty, about what touches you in that other person, wonder. My awareness on that front has increased over the years. The thousandth time with your wife can suddenly be the first time. Tenderness and intimacy can be new at a time when you don't expect it. That is the gold of your relationship.

Good friend [and writer - ed.] David van Reybrouck recently published an article about his favourite spot of the female body. He described the tendon on the inside of a woman's thigh, which can suddenly be so tight and contrasts with the roundness and elegance of the female body. That is something I have always found particularly beautiful too. That is looking with love. And when you look like that, you also love better, in my opinion. Then you know what life is about.'

5. What are you afraid to tell your parents?

'There was basically little I didn't dare tell my parents. My father was an officer in the administration of the Belgian Railways all his life, my mother devoted her whole life to her family. They were very traditional, Catholic people, but open-minded. Even during the time when I had changing relationships, they were always nice to whoever I brought home. They made me feel like they trusted me.

As a young man, I broke away from my Catholic background and vehemently opposed my parents. The young left-wing student I was, I thought they were bourgeois. I set myself off as an adolescent does: with whimsical clothing, long hair, rock 'n' roll and weed, and later by going politically leftist and challenging their Catholic outlook on life. Some things I should not have said. In my first book Space there is a sentence I still regret: "The milieu from which I stem is a spiritual forgetting pit." I particularly hurt them with that. My youngest sister threw that at me several times; she thought it was self-centred of me. She was right. In War and turpentine I corrected this image and described how much this "environment" gave me. Although she rarely showed any signs of being hurt, I would like to see my little mother again to say I am sorry. She passed away in 2002.

For the last 15 years of her life, the relationship between my parents and me was loving and harmonious. All the folds were smoothed out. Sigrid played a big role in that; she encouraged me to see my parents more often, to make them happy. Only when you get older and have children of your own do you realise what they have done for you and really start appreciating them. I am exceptionally lucky to be sixty-five and my father is still around, He is now ninety-five. We have come through all the storms of life and know: we can talk about almost anything. But we don't have to.'

6. What is your biggest pain?

'I think getting older is a pain. I had to learn to accept that. In my heart, I am still thirty. I am also under the illusion that I am still thirty physically, but that is disappointing. My body changes, I am stiff when I get up. It's over after three minutes, but I didn't used to have that. I also don't want Sigrid to see that I am stiff, then I feel humiliated. We are eighteen years apart in age. For twenty years that didn't matter at all. And now we both feel it is starting to play a role. While at sixty-four I actually have the life of a forty-six-year-old man: Sigrid is in a career change, we have a nineteen-year-old son, I have been very busy after winning the AKO Literature Prize. Normally it's quieter at sixty-five.

I used to be able to write in the greatest turmoil, but lately I need peace and quiet, otherwise it won't work. At the same time, I always had this longing for solitude. I find the social aspect of life a tall order. I am very social, but I also have a piece of impenetrable loneliness inside me. When I am alone, I find myself. Writing comes from my longing for solitude, not the other way around. When I spend a few weeks alone in our house in France, I feel euphorically happy and a lot of poetry comes out of me. After three weeks, I want to go home again. I am actually a married celibate.

Getting older doesn't scare me so much as repulsion: I don't want this.

Until I was 60, I thought it was all fine, but now I am struggling. I want to keep my energy, I want to be able to keep writing, to keep being the man I am for Sigrid. She gives me a lot of space, I can go to France if I feel the need. I would like to spend more time there, but at the same time I want to be there for her and our son. I have always taken credit for being the house husband. The grandma, who put tasty, nutritious meals on the table. I want to continue to be that too.

Death does scare me. I live far too much. I simply cannot imagine the whole of this world ceasing to exist in me. I can't resign myself to that.'

Flemish writer Stefan Hertmans (b. 31 March 1951) broke through in the Netherlands with the novel War and turpentine (2013), for which he was awarded the AKO Literature Prize, the Gouden Uil Publieksprijs and the Flemish Culture Prize for Literature. In 2016, he wrote the poetry gift for Poetry Week. Last autumn, his novel The convert, about an 11th-century refugee.

Hertmans grew up in Ghent in a Catholic family. In 1981, he made his debut as a writer with the novel Space (1981). Since then, he has built up an extensive and multifaceted literary oeuvre, comprising poetry, novels, theatre texts, essays and short stories. Well-known novels include To Merelbeke (1994), If on the first day (2001) and The hidden fabric (2008). Hertmans also published in a large number of newspapers and magazines. He combined his authorship until 2010 with a teaching job at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Ghent and taught and lectured in Paris, London, Vienna, Berlin and Washington, among other places.