Neues Stück 1 Seit sie - Ein Stück von Dimitris Papaioannou is a long title for an overwhelming piece, which Tanztheater Wuppertal is bringing to the Holland Festival this year.

Nine years ago, on 30 June 2009, a month before she was due to turn sixty-nine, Pina Bausch died suddenly. The world-famous and highly influential choreographer of experimental, haunting and peerless dance theatre left behind an orphaned company. After 35 years of continuous artistic leadership, Tanztheater Wuppertal was suddenly on its own.

Mum

Michael Strecker, who has danced with the company since 1997 and now plays a key role in Neues Stück 1, Seit sie by Dimitris Papaioannou, describes it as "the crew lost its mama".

"After being associated with the company for 20 years, it's frightening. You wonder if you can still function in other people's work. Whether anyone else still sees anything in you. I too have become so fused with Pina's work."

Michael Strecker is a disarming man, somewhere in his late forties I estimate. Tanztheater Wuppertal is extremely economical with biographical information About the dancers. Ekaterina Shushakova has only been with the company for a year. She is part of the newcomers, the 'babies', as Strecker endearingly calls them.

Wim Wenders

Prior to speaking with Dimitris Papaioannou the day after the premiere of Neues Stück I, Seit sie at the Opernhaus in Wuppertal last May, Strecker and Shushakova explain what it is like for them in the absence of that Pina repertoire to do, and how they fared with Dimitris Papaionannou.

Michael: "When Pina died, we felt orphaned, like a "crew, who lost their mama". Wim Wenders taught us that we could do something even without her, by making a film for her. And, of course, there were all sorts of commitments we could throw ourselves into, such as the series of urban plays we during the 2012 Olympiad in London have done. But actually, at the time, we were very afraid that someone would take over. So we worked with former dancer Lutz Förster, who took over as artistic director in 2013."

"We also found it scary to hire new dancers, people who had not worked with Pina. We wondered if we could find people, who suited the work, and us. Could we pass on the work at all? What could new people contribute? That process really took a few years. The company needed time. Some went through the grieving process, others put it away. After all, the company is made up of very different people. There were dancers who had spent their whole lives with Pina."

Someone from outside

"We really needed someone from outside, like Adolphe, who had distance and could redirect the process of processing into a new energy. Through her, we were able to allow the thought that we have Pina with us, that those beautiful pieces can be danced again, that the knowledge is there for that and that we can pass it on. And then it turns out that young dancers are really captivated by the old work."

Since 2017, Adolphe Binder has been the intendant of Tanztheater Wuppertal and is blowing a different wind. She not only engaged Dimitris Papaioannou and Alan Lucien Øyen to create new pieces but also attracted new dancers, including Ekatarina Shushakova.

Parent

Ekaterina: "It's very sad, to do her work without her presence. But it's also great to enter the world of those beautiful pieces, to become part of that tradition, passed on by people who did work with her. To touch the masterpieces. To work with each other in her absence. Everyone, including audiences around the world, has their relationship with the work in that way, even if only from pictures or videos. Her work is so influential. But without the direct experience, it's really very difficult."

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Jm70fMM3JAk

Michael: "We also realised as dancers that we were getting older, that we couldn't do the pieces as before. Besides, Pina loved her old dancers immensely, but she was also always taking on a younger generation. She loved putting different generations on stage, as a mirror of social reality. We didn't want to become a living museum. So we did have to take on new dancers. And that worked, if we didn't push them too much.

Who are we?

Pina's manner was never very articulate of: this is right, that is wrong. She actually only made suggestions, like: a bit more this maybe, or: not that I believe. So who are we to tell new dancers how it is? On the other hand, we do make our own decisions now. We cannot copy Pina. Transferring the repertoire is a very special process. At the same time, the new dancers are working with roles created for someone else. And that is the great thing about working with Dimitris, that we are all starting anew, that we are together in a new creation."

How did Dimitris put you to work?

Michael: "He asked us, like Pina, to figure things out, improvise, especially with the materials we use on stage. Pina asked you questions and left it up to you to find an answer. She determined whether it should be with text or without, but left you relatively free. Dimitris has a penchant for working everything out immediately, going into detail and reducing something to its essence. "He makes it right away his".

He naturally suffered from time constraints, a big difference from Pina, who had and took all the time. There was a period when she collected material. Then we played repertoire and she had her own process with the new piece. She only came back to things we had done when she started editing. And she released pieces without a title, told the audience that they were fragments, that it was not yet a full-fledged piece.

Swiss clock

Dimitris had to come to terms with the fact that we could not do what he wanted right away. Dimitris is super precise in form. He is like a Swiss clock, whereas we are used to working from an emotional idea. Pina was also very precise, but precise with emotions. Dimitris creates images. It's about form and timing. He talks a lot, he has a philosophical bent. It took a while before I could translate his ideas into something in or with my body. And sometimes it's also purely technical things, like in the kitchen scene, only one thing has to go slightly wrong there and the whole scene is lost. With Dimitris, it's often about the mechanics of illusion."

What do you think is central to this piece?

Ekatarina: "Difficult to establish that at this stage. The play is about life. It is a love letter to Pina, but is also about Dimitris's parents and their struggle with stereotypical roles, the battle of the sexes. There is a lot of symbolism in it, mythological references and references to fine art. For each of us, of course, Pina means something different. This performance is really Dimitris' Pina."

Michael: "It's funny. Pina always refused to talk about the interpretation of her pieces."

Ekatarina: "Apart from the precision of the form, the metaculous composing, Dimitris is actually very often about a certain atmosphere, an energy, a certain dynamic loaded with intentions, which Dimitris describes, which he needs for a certain moment or scene and which you try to shape as a dancer. It's about a certain presence."

Family constellation

Michael: "And it's also about relationships among ourselves. Recently, he used a kind of family constellation to make his vision clear to us, who we are in the play and how we relate. At the risk of going too far, you could say that the whole play is actually very personal to Dimitris, autobiographical almost."

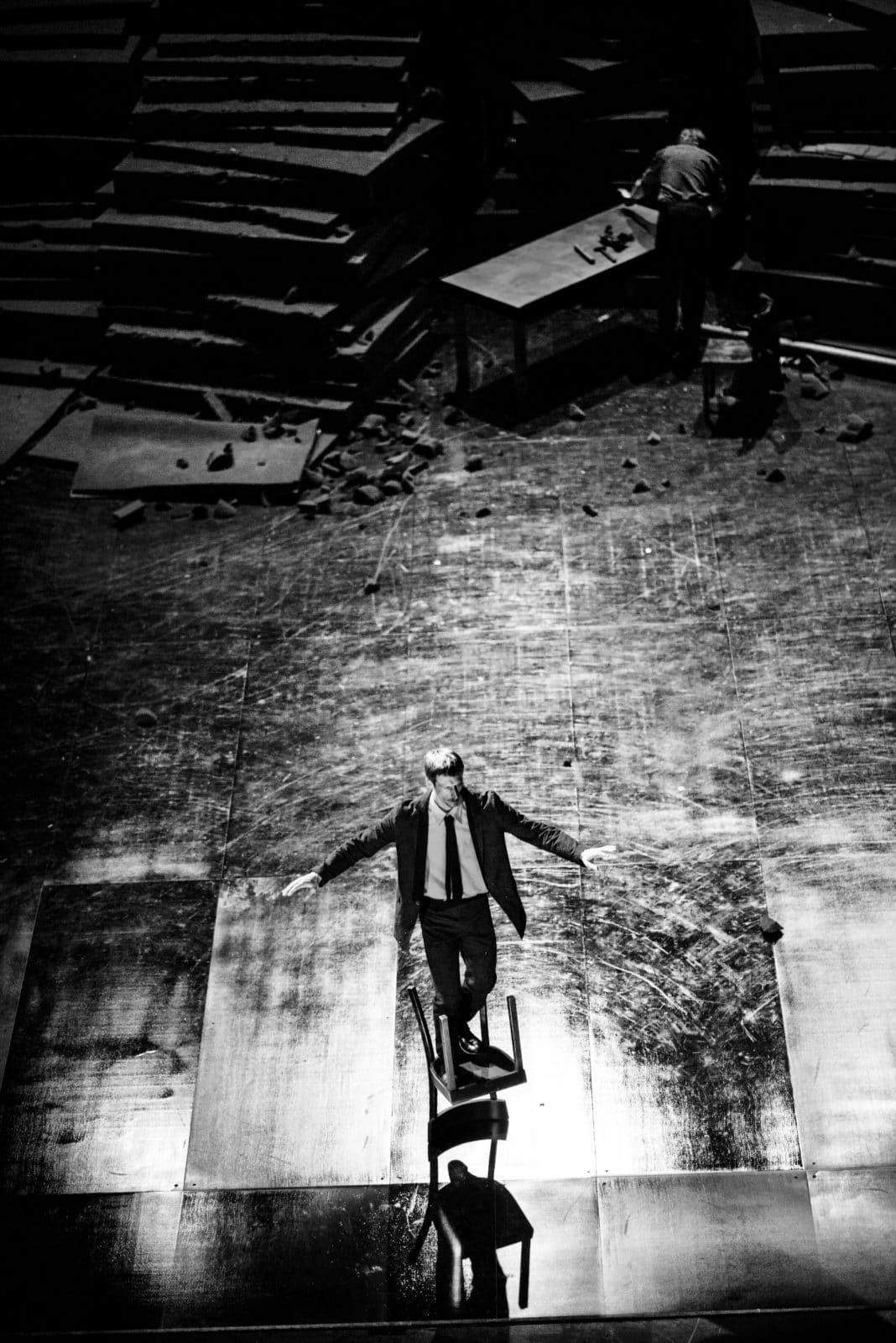

There is something about puppet theatre and circus in his work. As if everyone is absorbed in a very big trick special, with balance keeping and magic tricks and grotesque visions, which pass in rapid succession. A combination of theatrical grandeur and a very sober, almost raw approach.

Ekatarina: "He often talked about circus."

Michael: "That's really hard for us. It's very different from dance. You cannot afford any mistakes, "you cannot fake those tricks".

Ekatarina: "He is how Dimitris with no dance background engages with movement."

Never give up

Michael: "He is not necessarily concerned with how grand or special the trick is. Or whether it's going to be dramatic. Sometimes he also hides the tricks, they are barely visible. For him, it is more important to see how someone tries, maybe fails, and tries again. That really connects his work to Pina's and her idea of not giving up, never giving up."

Ekatarina: "You have to keep it alive.

Michael: "Yesterday at the premiere, the chairs were really not my friends. They kept falling. I knew it wasn't meant to be. But I had to keep trying, I didn't want to give up until I had them all together. I just trust then that's the right decision for the moment."

Pitfall

Pitfall

Strecker opens the performance, after the entire crew has made its way across the front stage via chairs. He clears the chairs by loading them one by one on his shoulder, which seems an impossible, doomed mission. The reference is clear. Dimitris Papaioannou does not mince words for a second, just as he does not mince words in the interview, for instance when asked what assignment he was given by Adolphe Binder.

Dimitris: "I had carte blanche in terms of my artistic choices. Why they chose me, you have to ask Adolphe. I can only say that she approached me three years ago, before I became hip in the international scene. The only question I asked myself was whether I was willing to voluntarily throw myself into this trap. I did it because I greatly admire Pina Bausch's work and have followed it all these years. I would never forgive myself if I passed up the opportunity to work with these people, to spend time with them, even though I know there is a risk involved and it could be misinterpreted."

Carte blanche

Where did you start from for this piece?

Dimitris: "It's about finding balance. 'A struggle of balancing in existence. What is the point, what is the fucking point. How do we construct meaning in our lives?" I'm only human too, asking big questions. I did Still Life, on the Sisyphus myth, a very existential theme. At 40, after spending three years at the Opening of the Games in Athens had worked on, an immense project, I was left with no ambitions. I had achieved everything I dreamed of, in one fell swoop. I had money, recognition, success. I was one of eight artists who had delivered work on this scale. I could ask myself what really concerned me, "real human issues that are not dirtied by cheap ambitions".

"I started making other work. And with this commission, it felt like quicksand I was sinking through, I had to deal with my ancestors, my origins, memories of my father, my grandparents, my childhood, the people I was taught by, who I learnt from. It all felt terribly old, all nostalgia."

Circus

The timing, the way the setting on stage is manipulated by the performers, the performers manipulate each other and people and things switch roles, is akin to animation and circus. Sometimes Papaioannou literally deploys the virtuosity of the acrobat, but often it is the magic of magic and illusion-theatre that he evokes, albeit in a paradoxical way, as the magician seems to be explaining his tricks.

"I have a nostalgia for old theatre genres, like the magic trick, the freak show, the circus. They are memories, which also remain alive through the work of artists, as with Fellini or Pina Bausch. There is a childlike kind of wonder possible in theatre as a medium of illusions, ideas and emotions. If it succeeds, and trying also always means failing, to create an illusion while showing how you put it together, then I think we are dealing with a better, a mature illusion. It becomes a conscious choice."

Illusions

The mechanics of theatre, of the trick but also of meta-montage, are constantly made visible by Papaionannou, which is in stark contrast to the illusions he nevertheless creates.

Dimitris: "Making a trick believable by showing the technique behind it means you have achieved a certain turnaround in the audience. I see theatre as a voluntary contract between theatre-makers and spectators. I would like spectators to actively and voluntarily surrender to the illusion. This is only possible if you leave them the space to not believe it, every moment. So the work can persuade people to take that leap into the dark, "a leap of faith", but it doesn't have to. This may also be the difference between entertainment and art. Entertainment wants to grab you by your claws, art allows you to keep your distance. I definitely have something to do with Brecht there. I work with a certain detachment, I also want to achieve a certain coldness in things."

Arte povera

What is also striking is the contrast between the simplicity of many gestures - something with a chair, something with a pile of mattresses, something with a dress and a lot of legs and arms - and the grandiose, overwhelming amount of scenes, which tumble over each other at an inimitable pace, so much so that as a spectator it almost drives you crazy.

Dimitris: "It's always a struggle for me, to be naive, very close to the arte povera remain, while at the same time increasing the layering of the composition so much that it comes close to a dream, to daydreaming. I am not David Lynch, but I love his work. Absurdity and surrealism come from the everyday, from mundane details we thought we knew how they worked. Turning a table into a boat produces a much stronger image than doing a boat with a boat. The illusion of the boat works better with the table. It demands a certain surrender from the viewer, "... this leap of faith. We invite the faith, but we need the shift".

Café Müller

Has your way of working at Tanztheater Wuppertal changed substantially?

Dimitris: "There are differences. It is the first time I am working with a company. Until now, I chose my performers per project. And, of course, the company has a huge history and a certain creativity. It's like I have been brought into a universe that they control, that they are entitled to, are the inventors of it. They know what they are doing. They have been doing Pina's work all these years. Of course, we have all been very conscious of what the trigger is, what the brief was.

When did you first come across Pina Bausch's work?

Dimitris: "I was nineteen, in the early 1980s, when I saw Café Müller. I was moved to tears. It was my first really convincing experience of theatre. Until then, I had only had that with films and painting. When Pina Bausch came to Athens that first time, it hit me like a bomb. High heels, long hair, long dresses and the gender-issue drama, men oppressing women - the Greeks didn't know what they were talking about. I studied painting, but was also into contemporary dance and developed my ideas for both. I was doing sets and costumes and make-up and trying out my first choreographic ideas. When I Café Müller saw opened up a whole new world."

Zoom in

In the performance, you not only play different genres, but you also use different channels. The visual, the dancing or moving, the conjuring, but also, for example, the sound, all have a very independent status of their own, which is perhaps what makes it so overwhelming.

Dimitris: "I need to work more on that, but of course I try to zoom in on different things. For me, it's about the shift in perception. How those children are playing on stage with different communication systems - what does a puppeteer do, or in the circus: what does the clown do, what does the acrobat do, what is a grande dame, and where are the animals?"

"And then I try to arrange transitions between the different perceptions, "small shows within the show". Someone is collecting chairs, chairs are falling and rolling, the balancing is a reality, but within that I try to keep the viewer engaged with different themes: this is a real balance, this is an illusion, this is dance, this is flirting with creating an image, as if it should be a painting, this is sound, ect.

Things their own value

"I force the spectator's eyes to look as if it were a painting. We do think that a painting is a static thing, but in fact it suggests a trajectory of glances, defining the path of experience. In this way, painters also work with time, and painting comes close to theatre, or a musical experience."

"But it's not easy. I try to look from the full width, like with a wide angle, keeping an eye on the edges of the image as well as the centre. And I try to feel when I want information where and how to connect those energies. It is a process, which I am slowly building. Not every detail needs to be seen by the audience. When you start working, things all have about the same value, the same measure. But over time, during rehearsals but also when you start playing, things take on their own value."