Searching for what I stand for and which way to go, time and again I come across facts that confuse and amaze me. I live in a country where only a single woman is in De Volkskrant top ten most influential people - in tenth place, that is. Only three out of 100 young Dutch millionaires from the Quote 100 his wife. Without exception, they deserve that spot by displaying their bodies.

I live in a world where forty per cent of thirteen-year-old girls are insecure about their looks. And that number has grown to seventy per cent when they are seventeen. One in three women over thirteen lives with an eating disorder. Media is still dominated by grain-thin, perfect models. And a newsreader on TV is constantly judged by what she wears, while her male colleague is judged by what he says.

Jap camp

I live in a world where women who want to show their power do so by following in a man's footsteps. Sometimes quite literally, as on the new version of The Night Watch starring Neelie Kroes as Captain Banning Cocq. A world in which women spend more money on cosmetics and personal care during their lifetimes on a cumulative basis than on their studies.

But there is also that other side. I also live in a world where a woman - just a girl still - arrived at the port of Rotterdam in the spring of 1946 with a suitcase of summer clothes in her hand, her feet on Dutch soil for the first time. Only her sister she took with her from the East Indies. She had to leave her mother behind, deceased from the effects of the Jap camp.

Girls are no longer the weaker sex

With her head held high, she enrolled in a nursing course. Even after she had two children, she continued to work. First in the hospital, later as a teacher. Even when her daughter's classmates were not allowed to come to her house to play because she was 'a black girl', she held her head up high. Even when the other mothers taunted her for not waiting for the children with a cup of tea when they came home from school, she held her head up. This woman is 94 now. This woman is my grandmother.

My grandmother was the exception, but now she is the rule. Girls are no longer the weaker sex. According to an article from De Standaard in June last year with the eloquent title 'Men on the precipice', girls today are smarter and more responsible than men, obtain degrees more often and show a greater sense of responsibility. They are also less prone to addiction and are less likely to be involved in an accident, giving them a longer life expectancy.

#Metoo

There is a change going on in the world. Women - and increasingly men too - are questioning the way we view women. In October 2017, the world was rocked by one two simple words: Me Too.

Anyone posting 'hashtag' MeToo indicates they have faced sexual harassment or assault. Perhaps for the first time ever, women - as well as men - are raising their hands: 'MeToo, me too'. Not only do the victims of sexual harassment redeem themselves from the shame that has long clung to such matters, but it is also, above all, a statement: society needs to change.

We live in a world where we find it acceptable for a woman's lovemaking to end in tears. Where people wonder why a woman doesn't just leave when a man doesn't treat her well. The truth is, women are brought up with the idea that pain is an accepted and unavoidable part of life. From the moment she is born, she is told to be beautiful above all else. And to be beautiful is to suffer pain. From the first braids in the hair to 9-centimetre-high heels: to be beautiful is to suffer pain.

Painless sex

Let's talk about women and pain. Research shows that 30% of women experience pain during sex, and a large proportion of these women do not tell their partner. 'Good sex' for a woman means 'painless sex', where for men it is about how satisfying the sex is. There have been 1,954 studies on erection problems. On the pain women experience during sex, only 43.

Pain, humiliation and shame are no longer accepted things that simply come with being a woman. The hashtag #MeToo gained popularity after Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein was accused of sexual harassment by several women. Now, a year later, the term is also being used to give face to other cases involving sexual harassment and/or abuse of power. For instance, the term was used by Léon Hanssen in an article in Trouw on 3 February 2018, in which Hanssen called on the museum world to discuss nudity in art. Sandra Smallenburg did the same in the NRC with the stonkingly good article "Should dirty men leave the museum? #ArtToo: New prudishness."

It's not about prudishness

But Sandra is wrong: this - what I am saying here - is not about prudery. The problem is not in showing the human body. Censorship means as much as: you should be ashamed of your body. Or, perhaps even worse - eroticism and sexuality are reserved for dirty males. The naked body is part of life, as is sex. But only to the liking of both parties. If art is the free zone in which precisely everything is allowed to be questioned - we may still not want to display the outcome of that questioning in the public space.

Let's mention some examples. You can find this magnificent work by Bernini in the Galleria Borghese. It is perhaps the most impressive, breathtaking sculpture I have ever seen. Look how Pluto's firm grip on the floundering Proserpina is visible in the marble, so lifelike. Her agony, his determination. Thousands of people visit the Galleria Borghese and marvel at this sculpture. The light, the cool marble, the lifelike facial expression.

Then the title: Ratto de Proserpina, The Rape of Proserpina. Pluto wanted to possess the young girl Proserpina, and take her to the underworld. Proserpina resisted, but is defenceless.

Victim blame

Rape in art, it is not as exceptional as you might think. Medusa, a hideous woman with snakes on her head, who could turn men to stone just by casting a glance at them. Most people don't know why Medusa is such an ugly thing. According to legend, a priestess in the temple of the goddess Athena was famous for her beauty. Medusa had sworn an oath to always remain a virgin in order to be a symbol of purity, an example to the people. But the God of the sea, Poseidon, put a stop to that. He raped Medusa in the temple of Athens.

Medusa thereby lost not only her function as a priestess but also her right to marry. A woman - as this shows - was property. Athena punished Medusa after she heard what had happened, exiling her to an island, turning her hair into snakes and making her face so unattractive that she turned anyone who looked at her to stone. She is isolated and exiled from society. She is the culprit. And what do you think Poseidon gets for punishment? Nothing. He is a powerful man, and so he is expected to take whatever he desires.

Concealed

The example of Medusa and Proserpina does show that Greek mythology is riddled with rape stories. Greek mythology, the cradle of our Western society. Paintings with these themes are so popular in Western art history that there is even a term for them: heroic rapes.

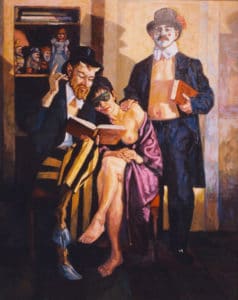

These works of art paint an almost romantic picture of these terrible events. In this example by Rubens - another story from Greek mythology - at first glance, the gentlemen seem to be playing a game of tag that has gotten out of hand. Or are they reassuring the ladies, startled by the prancing horses? Even the Angel seems to have no problem with two poodle-naked ladies being dragged along on ferocious horses.

In Greek mythology, the outcome of a rape case is often only detrimental to the woman: victim blaming, we call it today. The same themes also play out in rape cases today. Every time a rape victim is asked, "Why was your dress so short?" or "Why did you go home with him?" we do the same thing we did to poor Medusa in this Greek myth.

Rape we disapprove of, no doubt. But, should we remove violent scenes we morally disapprove of from the museum? I don't think so. What matters is what context is given to the work. Museums often choose to talk about the artist's virtuosity, the lighting, the fabric expression and perhaps some context about the patron. But how many museums address the ferocity of the performance? How many museums address the sexual tension in this work? The feelings of lust for the young girl that Bernini is trying to evoke? Right yes. We'd rather not burn our hands on that.

Innocent nude

But what about 'innocent' nudes in art? Rape is one thing, most of us still think something of that. But what about all those naked bodies, displayed in front of us like crispy biscuits on a platter?

The discussion about how we view women in art is not new. British critic John Berger opened the debate on our view of art back in 1972 with 'Ways of Seeing', a series on the BBC. He wrote: 'A woman is always in the company of others, even when she is alone, by her own idea of herself. When she walks through a room crying for her dead father, she cannot help but imagine herself walking and crying. She is taught from her earliest childhood to observe everything she sees and does, because how she comes across to others - and especially how she comes across to men - is vital to our definition of a successful life.'

John Berger already made a good attempt to make the public aware of the stories behind art, and not just look at the beauty of what hangs in front of us. In the latest episode of 'Ways of seeing', Berger describes how the goddess in art has been replaced by the models in contemporary advertising, as you can see in this example.

Target

If you think these ads are meant for men, you are wrong. Advertising tells us that - by buying a product - you can transform into the people who are already transformed - the advertising heroines. These are the people we measure up to and want to surround ourselves with. A woman in lingerie is coveted by men and viewed with envy by women. Glamour, jealousy and 'looking' - this is what our entire fashion and social media obsession revolves around. Victoria's angels embody the ultimate fantasy, and the annual catwalk show is watched by millions of people worldwide, the majority of whom are women. Their message is: by purchasing these products, you can transform. With their springy stride on the catwalk, the Angels appear a lot more passive than the nudes in painting, but the impact is the same: they exist to arouse desire, perfection incarnate.

Back to painting. "You paint a naked woman because you enjoy looking at her. Depict a mirror in her hand and you call the painting 'Vanitas', condemning the woman whose nudity you have depicted for your own pleasure." - John Berger, Ways of Seeing (1972)

In this quote, John Berger describes the double standard by which we look at women. The beautiful female body in this painting by Albert Penot - the perfect round buttocks, the delicate soles of her feet, her face hidden - is at the mercy of our gazes. Looking is not innocent. By choosing to rest our eyes on her, we become voyeurs. She is the subject of our lustful gazes. But the apple in her right hand - still just visible above her head - and the title of this work 'The Daughter of Eve' make her the subject of blame. Eve: the temptress who led Adam to sin and through whom we must now suffer on this earth. She is the source of evil, the bad influence.

Original sin

Original sin is a common thread in Western history - often reversing the blame for immoral acts. Women's temptation is so great, a man cannot possibly say 'no' to it, it is often claimed. The title of the work, 'Daughter of Eve', refers to this original sin. All women are potentially seductresses, out to drive innocent men mad with desire. Instead of a mirror, Penot gives his model an apple in his hand, thus condemning the woman whose naked body he painted for his own pleasure.

The female nude in Western art - hairless, voluptuous, fair-skinned and flawless as a pearl - has always been meant to feed a male sexual appetite. These women have no needs of their own. They are made to look at, depicted in such a way that they are best visible to their male viewer, ready to be consumed.

Male gaze

That the 'male gaze' or 'male-gaze' - by which this phenomenon is referred to - is not only limited to women, is well reflected in Meerman's art. Until a few decades ago, the male genitals were hardly depicted in art, with the exception of that of baby Jesus. This has changed in recent decades, partly thanks to the growing acceptance of homosexuality in the street scene.

This work from Bas Meerman is a good example of this. This man stares seemingly impassively in our direction, hands loosely on his hips, his sex prominent. If he were actually standing here naked in front of us, would we have looked at him just as extensively? Probably not. By depicting a man like this, he becomes an object of lust- regardless of his sex.

Don't get me wrong, this story I am doing here is not about 'the wrong man' or 'the dirty man'. It's not even about 'wrong or dirty art'. It is about being aware that depicting people - and more so, naked people - is not innocent. To depict a woman is to own a woman. She becomes an object. The same goes for depicting a naked man - look at Bas Meerman's example - but because of centuries of inequality in the power relations between men and women, it is precisely depicting women in this way that a growing group of people are uncomfortable with. And we notice this.

Affaires

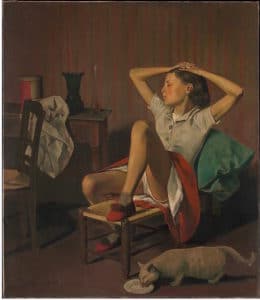

The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York refused to remove a painting by artist Balthus from the museum last year, even after 10,000 people signed a petition to that effect within a week. The 80-year-old artwork would - according to the protest group - encourage paedophilia. You might think this is a typical example of American conservative prudery.

But the Almelo court's decision to remove the work by artist Joep Gierveld - which has hung in the Almelo courtroom since 1992 - is reason to believe that art in public spaces is also under discussion in the Netherlands. A complaint by a woman from Hengelo prompted court president Bart van Meegen to move the painting to a private part of the building.

Vera Bergkamp - D66 politician - thought it was reason enough to ask parliamentary questions last September 25 about why the painting was removed and questioned whether the action was an attack on the essence of art.

Vera Bergkamp - D66 politician - thought it was reason enough to ask parliamentary questions last September 25 about why the painting was removed and questioned whether the action was an attack on the essence of art.

Public space

"An attack on the essence of art", nice phrase, but what does it actually mean? Something like: that in art everything should be allowed and possible. Art is seen as a sanctuary where boundaries are pushed, and rules are allowed to be broken. That sounds nice in theory, but in practice it has some consequences.

In the case of the painting in the Almelo court, it is about public space. You don't choose to be in court, often you have to, whether you want to or not. When you then come face to face with a painting that reminds you of the sexual abuse you were victimised by, it is incredibly distressing. It is different in a museum, which you consciously buy a ticket from and which you can expect to see nudity.

Frenetic

It is easy to immediately condemn the woman - who protested against this work - for her request to remove it. In the past, her complaint would probably have been waved away. As the artist's brother - Joep Gierveld - himself says: "The President of the Court - Drewes loved it. As did Breitbarth, also one of the defining people of the time. It says something about our society that we are suddenly so fussy about a painted woman's breast."

Society has changed dramatically with the advent of the internet. First, the influential gentlemen of the court determined what could be seen in the premises. They were the authority, the institution. Just like the Museum was in an institution, and the church. But with social media, everyone has a voice, and the institutions are no longer the powerful strongholds with no accountability.

Tired

Hashtag #MeToo. Enough with the MeToo now, it sounds tired after a year. Meaning: can we get back to business as usual? But we can't. Because 'normal' was not normal. The greatest common denominator of the under #MeToo surfaced vice cases is the systematic looking down on women. The men who grovel at them regard them as covetable toys at best. Their feelings don't count, they don't exist.

People no longer want to be seen as toys. We can't get around it. Museums can't get around it. So, I invite you to look again at all that nudity in painting. All those naked bodies that we are no longer surprised by. Because it's only a matter of time before someone stands up again and speaks out to ban this kind of work. Watch and judge for yourself.